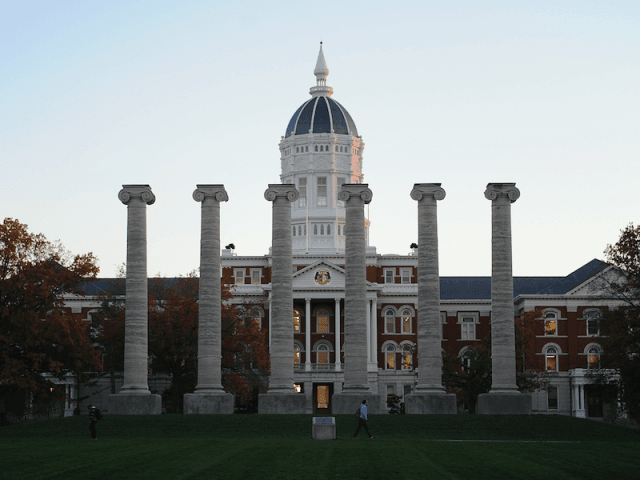

In 1967, University of California president Clark Kerr was fired by the Board of Regents for being too lenient in dealing with student protests. On Monday, Tim Wolfe of the University of Missouri resigned because he felt he had not been lenient enough.

The contrast, over fifty years of student protest, reveals both how radical students have become, and how cowardly the liberal academic establishment is today in standing up for its own supposed values.

The issues that triggered the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in 1964 were real. The civil rights movement was raging, and students wanted to advocate for the cause inside the campus gates. Later, they moved on to protest the Vietnam War–a conflict that implicated students directly because of the draft.

Today, students are motivated by a myth about racist police in Ferguson, Missouri, and are trying to suppress free speech on campus, not expand it.

In 1964, students sat down around a police car on campus Berkeley to protest the arrest of one of their classmates. They proceeded to hold a “teach-in” where everyone could speak–even those who disagreed with the them.

Last month, students surrounded Wolfe’s car in an off-campus parade to force him to acknowledge their demands. He still blames himself for not stepping out to talk to them–as if they had any intention of having a real conversation.

And yesterday, the students forced journalists out of their “safe space” on campus, in defiance of the Constitution, the law, and the principle of academic freedom. Students and professors assaulted photojournalist Tim Tai, and one activist even called for “muscle” to remove a student photographer from the protest, where he clearly had a right to be.

That activist was later identified as University of Missouri Communications Assistant Professor Melissa Click.

Faculty radicalism is nothing new. The demonstrators of the 1960s grew up to be the professors and administrators of today. They teach students that activism is romantic, that it is the most authentic mode of politics–that it is ‘what democracy looks like.” It was the radical left-wing arts and sciences faculty that forced Lawrence Summers out of the Harvard presidency in 2006 over benign comments he had made at a conference on women and science.

But the students are different today. Ten years ago, the Harvard students rallied around Summers, recognizing that he was the victim of an assault on academic freedom by leftist professors of a generation to whom they could barely relate. Today, students are often more radical than their teachers. They are inspired by the “community organizer” in the White House, who supports the demonstrations at Missouri, and celebrated the resignation of its president.

A recent survey by the William F. Buckley Jr. Program at Yale–a student-run free speech organization now also under physical attack–showed just how radical students have become: “By a margin of 51 percent to 36 percent, students favor their school having speech codes to regulate speech for students and faculty….One-third of the students polled could not identify the First Amendment as the part of the Constitution that dealt with free speech.”

In the 1960s, voters shocked by student unrest elected Ronald Reagan in California and Richard Nixon nationwide. But the youth of that era, and the next, grew up to believe in protest for its own sake.

The White House’s Josh Earnest said the lesson of Missouri is that “a few people speaking up and speaking out can have a profound impact.”

Yet these “few” reject the freedoms of the many–freedoms in which their elders stopped believing long ago.

Opening paragraph edited for clarity.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.