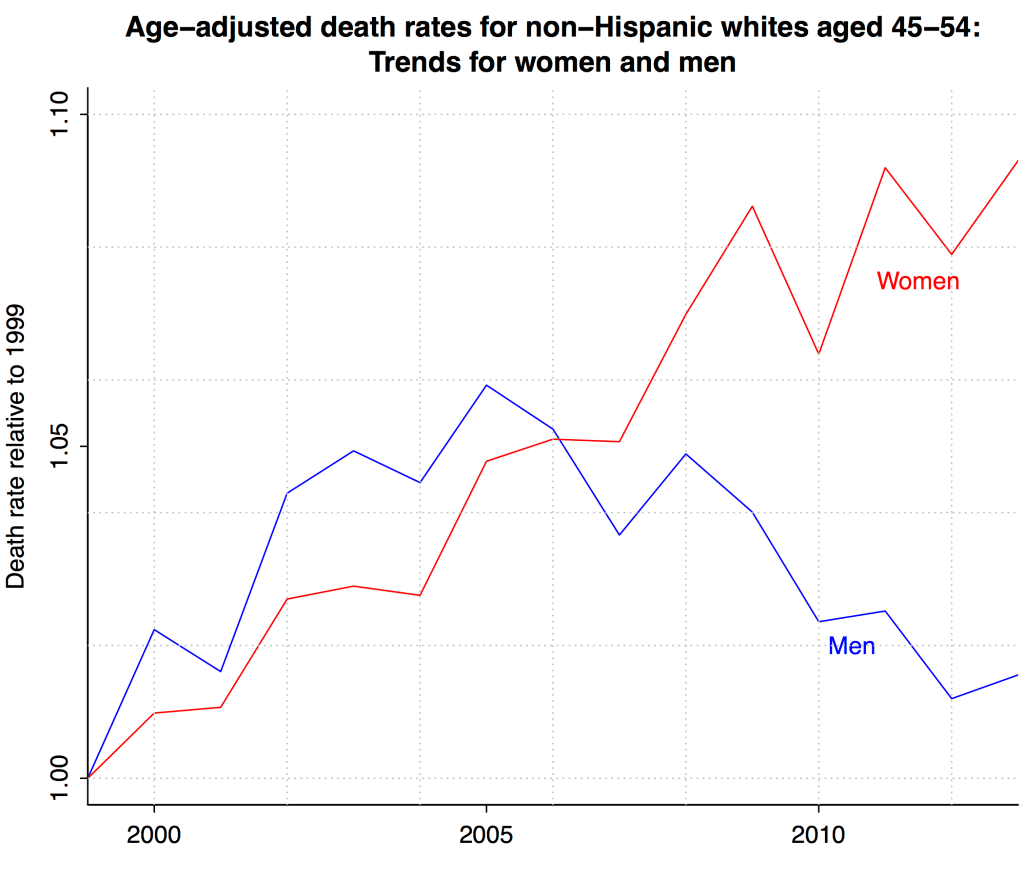

A researcher who investigated the new study that shows increased death-rates among middle-aged, middle-class whites has revealed something even more jarring — since 2005, all the extra dead were women, not men.

“The death rate has been rising for middle-aged white women and declining for middle-aged white men” since 2005, said the author, Andrew Gelman, a statistics professor at Columbia University. “Not by a lot – we’re talking a change of 4% over a decade – but this is what we see,” he added.

Middle-aged white males have seen a slight decrease in mortality over the past decade, but that gain has has been offset and hidden by rising death rates for middle aged white women, he said.

Mortality rates for men in this age group were rising from 1999 through 2005, but appear to have leveled off and turned downward since then, Gelman showed.”We’re so used to the narrative that things are getting worse for men, ‘It’s so hard to be a guy in the modern era,’ etc.,” Gelman wrote.

But “it’s the middle-aged women who are doing worse” in the trend lines, he wrote.

“We’re so used to the narrative that things are getting worse for men, ‘It’s so hard to be a guy in the modern era,’ etc.,” Gelman wrote. But “it’s the middle-aged women who are doing worse” in the trend lines, he wrote.

His charts show the trends clearly;

Still, as always, men still tend to die younger than women, he said. “Of course the absolute death rates remain much higher for men than for women, that’s just how things always are,” he said.

Men die earlier for a host of reasons, including reckless behavior, more workplace accidents and injuries, and less use of health-care services.

Gelman is not trying to debunk the bombshell study by Princeton economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case. Those authors have always encouraged further exploration of their data.

Gelman discovered the higher female-death rate while using the study for additional research. For example, Gelman says statistical analysis can be skewed by the chosen definition of “middle age.” That’s because death-rates start rising at age 45, and have doubled nine years later, at age 54. As the U.S. population ages, and the number of people from the Baby Boom age into their fifties, researchers should expect a correspondingly higher numbers of deaths in the 45 to 54 demographic.

Deaton looked over Gelman’s age-related critique and responded that adjustments for an aging population could explain some, but not all, the surge in middle-age mortality.

Deaton and Case theorized that over-medication might be a major cause of rising middle-age mortality rates. They pointed out the dramatic increase in patients who reported chronic pain to their doctors, and the higher availability of prescription drugs for the middle-aged white demographic. This could still be a valid hypothesis if Gelman’s take on the data is correct. Women are said to be generally more likely than men to seek medical advice, particularly for mental-health issues.

On the other hand, suicide was mentioned as a possible cause for elevated middle-age mortality rates, perhaps in conjunction with prescription drug dependency. But while middle-aged people commit suicide more often, women have far lower suicide rates than men.

Women are also at least as vulnerable as men to the social forces that have been considered as factors in rising mortality rates: the decline of marriage and traditional families, fading career prospects, and economic anxiety.

Since 2008, for example, women have been hit harder by the collapse of the government-pumped real-estate bubble in 2007. For example, Breitbart reported in August 2015 that the population of U.S.-born working women had still not recovered all the jobs lost in the 2008 crash.

“All net employment gains among women since the beginning of the recession have gone to foreign-born women, according to data released Friday from the Bureau of Labor Statistics… [Since December 2007] native-born women lost a net 64,000 jobs… 59,322,000 employed native-born women [were employed] at the beginning of the recession and last month’s [data showed] 59,258,000 employed native-born women.”

After the Deaton and Case study was published, it was suggested that women might be better able than men to cope with middle-age malaise, because they tend to have better social support networks.

What if that isn’t really true any more in the social-media age? What is women have traded some of their intimate friendships for more remote, less fulfilling “Facebook friends?” The development of Internet culture would track fairly well with the beginning of the mortality-rate climb, as did the increase in prescription drug use.

The loss of community amid growing diversity is a well-documented phenomenon, with a wide variety of suspected causes, ranging from increased mobility and declining home ownership (making people less likely to put down roots in stable neighborhoods) to the political drive for ethnic diversity which deliberately breaks up communities that share values and tend to have more well-developed social networks.

The decline of organized religion also leaves many people feeling less connected to a supportive community.

It remains troubling that in a time of rapidly advancing medical technology – and, society would like to think, increased awareness of preventive health measures, including diet and fitness – a particular demographic would either display increased mortality, or lag substantially behind a generally improving trend.

Something started happening to middle-aged whites around the turn of the century, and there is no single obvious cause.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.