Fourth of July is known as Independence Day mostly because it is emblazoned on the Declaration of Independence.

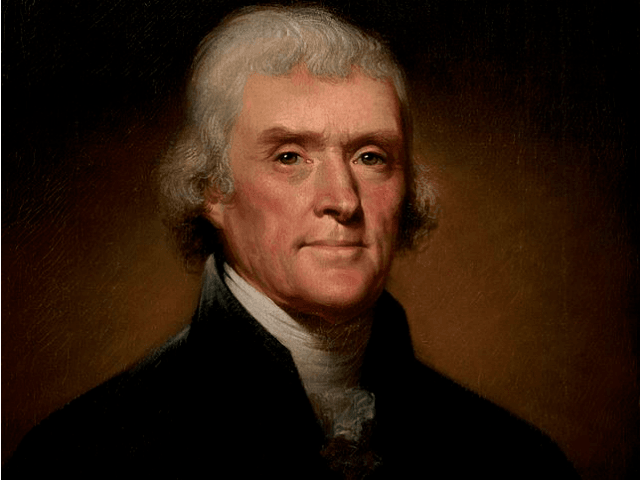

The Continental Congress actually voted for independence two days earlier, on Tuesday, July 2nd, 1776 and prevailed on Thomas Jefferson to draft a statement. The delegates then spent the next two days debating Jefferson’s language, finally agreeing on Thursday, July 4th.

The first publication of the Declaration of Independence did not occur until the following day, in the print shop of John Dunlap. His work was overseen by the “Committee of Five”—Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert R. Livingston—which was charged with making sure only the approved text made it out to the 13 colonies.

John Adams initially thought that the day of the vote would echo through the ages as the day the American colonies declared a new epoch had dawned on the earth. But a year later, Philadelphia held a party to commemorate America’s independence on July 4th and we never really looked back.

One of the overlooked sources for Jefferson’s early draft was a now largely forgotten pamphlet written by Judge Samuel Sewall in 1700 titled , “The Selling of Joseph: A Memorial.” It is a remarkable document, one of the earliest antislavery declarations published in the American colonies.

It’s very much a religious essay. The odds are that Sewall, a prominent Boston Puritan, actually read it in his church, the Old South Meeting House, on Sunday, June 23rd, the day before its publication. Eight years earlier he had done something very similar, publicly declaring his repentance for his role in the Salem witchcraft trials.

In his famous diary, which is the best contemporaneous record we have of Puritan life in New England, Sewell wrote that he had long been “much dissatisfied” with what he describes as “the Trade of fetching” slaves from Africa. Eventually, events in Boston—a lawsuit to free two slaves “unjustly held in Bondage” and a motion to impose a steep tariff on imported slaves—spurred him to publish his objections to slavery.

The title of Sewall’s pamphlet is a reference to the story in Genesis of Joseph being sold by his brothers into slavery in Egypt. “Forasmuch as liberty is in real value next unto life: none ought to part with it themselves, or deprive others of it, but upon most mature consideration.”

Perhaps the bit that will sound most familiar to contemporary American ears comes next. “It is most certain that all men, as they are sons of Adam, are coheirs; and have equal right unto liberty, and all other comforts of life,” Sewall wrote.

Abstract the religious sentiment a little and add a bit more music to the phrasing, and this sounds a lot like Jefferson’s phrase: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Sewall’s argument against slavery is very much the argument of the Declaration of Independence: that all men are by nature equally free and independent. Just as Jefferson’s argument hinged on the idea that no man has a natural right to govern another, Sewall uses this as a basis of his attack on slavery.

“Originally, and Naturally, there is no such thing as Slavery,” Sewall writes.

Although Sewall’s position was supported by some of the leading Puritan intellectuals of his age, it would not become widespread on American soil for several decades. But the early seeds of abolitionism were planted in his pamphlet and, it appears, from his pamphlet into the Declaration of Independence.

The church where Sewell likely read his pamphlet on the Sunday before publication would later be the same one where Ben Franklin was baptized. Samuel Adams became a deacon there.

The Sunday before its publication was June 23rd under the Julian Calendar in use in Boston back in 1700. That calendar officially went out of use on September 2, 1752 in the British colonies. Twelve days were lost in the change over to the Gregorian calendar, so that the following day was September 14th.

If the Gregorian calendar were in place in Sewell’s time, the day he would have read his antislavery argument would have been July 4th and his pamphlet would have been published on July 5th.

Sometimes in the course of human events we detect what looks like the fingerprints of Providence.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.