Lee Iacocca, the auto industry executive and master pitchman who put the Mustang in Ford’s lineup in the 1960s and became a corporate folk hero when he resurrected Chrysler 20 years later, has died in Bel Air, California. He was 94.

In the words of the Detroit Free Press, Iacocca was the “[f]ather of the Mustang, midwife to the minivan, rescuer of Chrysler Corp., [and] restorer of the Statue of Liberty.”

Two former Chrysler executives who worked with him, Bud Liebler, the company’s former spokesman, and Bob Lutz, formerly its head of product development, said they were told of the death Tuesday by a close associate of Iacocca’s family.

In his 32-year career at Ford and then Chrysler, Iacocca helped launch some of Detroit’s best-selling and most significant vehicles, including the minivan, the Chrysler K-cars, and the Ford Escort. He also spoke out against what he considered unfair trade practices by Japanese automakers.

Chrysler Chairman Lee Iacocca, right, waves as he steps into the first K-Car at ceremonies in Detroit, MI, on August 6, 1980. (AP Photo/Dale Atkins)

The son of Italian immigrants, Iacocca reached a level of celebrity matched by few auto moguls. During the peak of his popularity in the ’80s, he was famous for his TV ads and catchy tagline: “If you can find a better car, buy it!” He wrote two best-selling books and was courted as a presidential candidate.

But he will be best remembered as the blunt-talking, cigar-chomping Chrysler chief who helped engineer a great corporate turnaround.

Liebler, who worked for Iacocca for a decade, said he had a larger-than-life presence that commanded attention. “He sucked the air out of the room whenever he walked into it,” Liebler said. “He always had something to say. He was a leader.”

In recent years Iacocca was battling Parkinson’s Disease, but Liebler was not sure what caused his death.

He remembers that Iacocca could condemn employees if they did something he didn’t like, but a few minutes later it would be like nothing had happened.

“He used to beat me up, sometimes in public,” Liebler remembered. When people asked how he could put up with that, Liebler would answer: “He’ll get over it.”

In 1979, Chrysler was floundering in $5 billion of debt. It had a bloated manufacturing system that was turning out gas-guzzlers that the public didn’t want.

When the banks turned him down, Iacocca and the United Auto Workers union helped persuade the government to approve $1.5 billion in loan guarantees that kept the No. 3 domestic automaker afloat.

In his book Car Guys vs. Bean Counters, Lutz recalled how Iacocca faced tough questioning from members of Congress when he went to Capitol Hill to request the loan guarantees.

According to Lutz, “One inquisitor asked (this isn’t an exact quote, but a reconstruction from memory), ‘Mr. Iacocca, why should we ask this of the American taxpayer? Wouldn’t the money be better allocated to new rail systems and subways? Those, Mr. Iacocca, are affordable transportation for the masses!’ In one nanosecond, Iacocca shot back, ‘And what the hell do you think the Chrysler Corporation is?’”

“Chrysler got the loan guarantees, paid everything back early, brought a return of over $40 million to the U.S. taxpayer, and went on to decades of success,” Lutz noted.

Liebler said Iacocca is the last of an era of brash, charismatic executives who could produce results. “Lee made money. He went to Washington and made all these crazy promises, then he delivered on them,” Liebler said.

Iacocca wrung wage concessions from the union, closed or consolidated 20 plants, laid off thousands of workers, and introduced new cars. In TV commercials, he admitted Chrysler’s mistakes but insisted the company had changed.

The strategy worked. The bland, basic Dodge Aries and Plymouth Reliant were affordable, fuel-efficient and had room for six. In 1981, they captured 20% of the market for compact cars. In 1983, Chrysler paid back its government loans, with interest, seven years early.

The following year, Iacocca introduced the minivan and created a new market.

Lee Iacocca cuts the ribbon during a ceremony introducing the 1981 Chrysler imperial, on Friday, October 11, 1980 in New York. (AP Photo/Kaye)

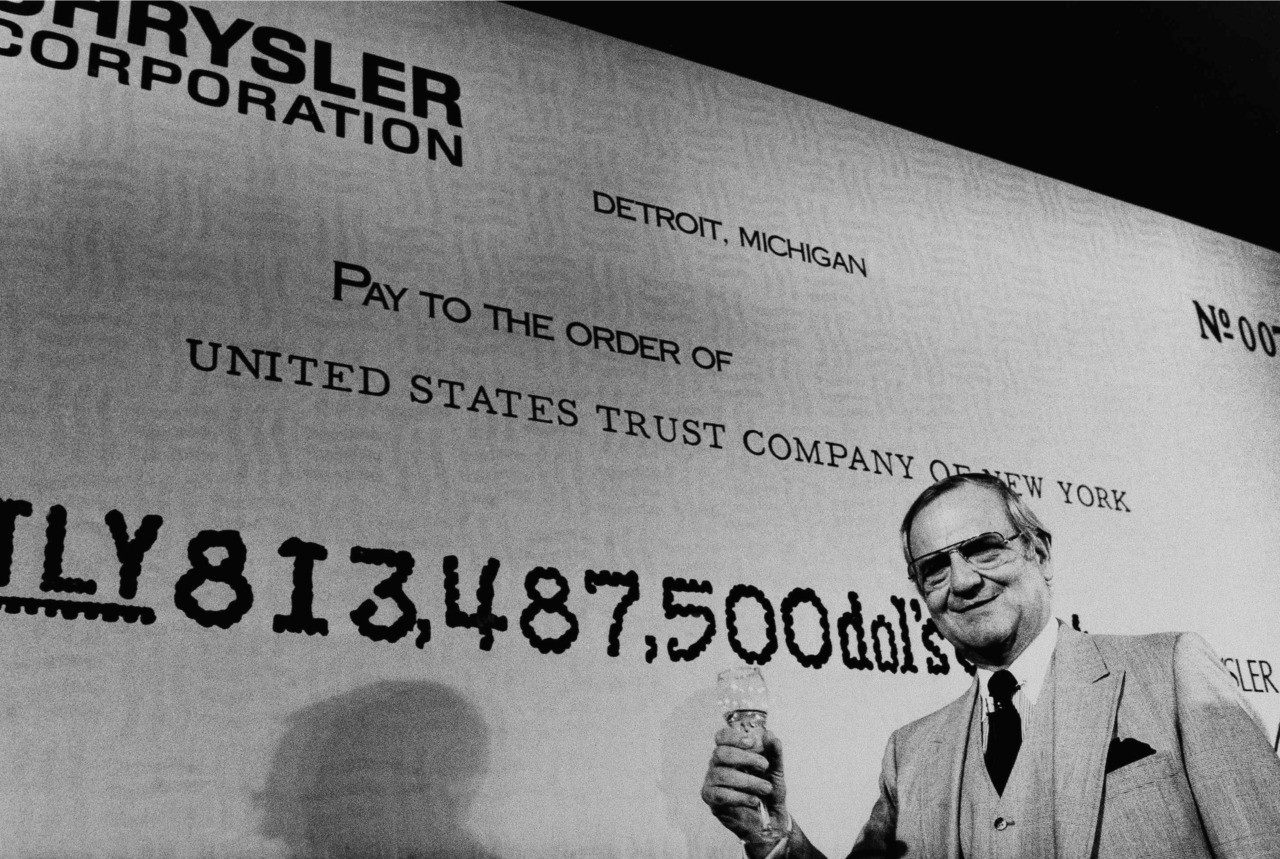

In this photo from August 12, 1983, Iacocca lifts a glass of champagne while standing in front of an enlarged version of the check for $813,487,500, which was the amount of the loan, plus interest, that Chrysler borrowed from the federal government. Iacocca handed the check to the government that day, paying U.S. taxpayers back seven years ahead of schedule. (AP Photo/Marty Lederhandler)

But in the years before his retirement in 1992, Chrysler’s earnings and Iacocca’s reputation faltered. Following the lead of Ford and General Motors, he undertook a risky diversification into the defense and aviation industries, but it failed to help the bottom line.

Still, he could take credit for such decisions as the 1987 purchase of American Motors Corp. Although the $1.5 billion acquisition was criticized at the time, AMC’s Jeep brand has become a gold mine for now Fiat Chrysler Automobiles as demand for SUVs surged.

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles issued a statement Tuesday night praising Iacocca’s “historic role in steering Chrysler through crisis and making it a true competitive force.”

President Ronald Reagan meets with auto industry executives, including GM President Roger Smith, to Reagan’s right, Ford President Phillip Caldwell, center, and Chrysler President Lee Iacocca, left, on Friday, December 19, 1981, at the White House. (AP Photo/Dennis Cook)

Iacocca was born Lido Anthony Iacocca in 1924 in Allentown, Pennsylvania. His father, Nicola, became rich in real estate and other businesses, but the family lost nearly everything in the Depression.

After earning a master’s degree in mechanical engineering at Princeton University, Iacocca began his career as an engineering trainee with Ford in 1946. But the extrovert quickly became bored and took the unconventional step of switching to sales.

He said a turning point in his career came in 1956, when he was assistant sales manager of the Philadelphia district office ranked last in Ford sales nationwide. Iacocca devised a financing plan called “56 for 56,” under which customers could buy a 1956 Ford for 20% down and payments of $56 a month for three years. The district’s sales shot to the top, and Iacocca was quickly promoted to a national marketing job at company headquarters in Dearborn, Michigan.

By 1960, at age 36, Iacocca was vice president and general manager of the Ford division.

“We were young and cocky,” he recalled in his autobiography. “We saw ourselves as artists, about to produce the finest masterpieces the world had ever seen.”

Iacocca’s first burst of fame came with the debut of the Mustang in 1964. He had convinced his superiors that Ford needed the affordable, stylish coupe to take advantage of the growing youth market.

As the Detroit News recounts:

With a group of like-minded young executives, [Iacocca] formed what became known as the Fairlane Committee named for the inn where they met for brainstorming dinners to discuss how to design a low-cost, sporty car that would entice younger, more affluent families to become two-car households.

“It had to be a sports car but more than a sports car,” Iacocca wrote in his memoir. “We wanted to develop a car that you could drive to the country club on Friday night, to the drag strip on Saturday and to church on Sunday.”

The Mustang, introduced at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York, was an unqualified hit. Iacocca and the car appeared on the covers of Time and Newsweek, with Time calling him “the hottest young man in Detroit.” As for the car itself, Time swooned: “Priced as low as $2,368 and able to accommodate a small family in its four seats, the Mustang seems destined to be a sort of Model A of sports cars, for the masses as well as the buffs.”

Ford sold more than 400,000 Mustangs during the first model year. The car’s styling captured young buyers, and Mustang clubs sprang up around the country.

In 1970, Iacocca was named Ford president and immediately undertook a restructuring to cut costs as the company struggled with foreign competition and rising gas prices. His relationship with Chairman Henry Ford II became strained, and in 1978, Ford fired Iacocca. Henry Ford II later described Iacocca as “an extremely intelligent product man, a super salesman” who was “too conceited, too self-centered to be able to see the broad picture,” according to interview transcripts published by the Detroit News.

Iacocca got the last laugh. He was strongly courted by Chrysler, and he helped cement its turnaround in the 1980s by introducing the wildly successful Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager minivans.

In a statement Tuesday, Ford Motor Company’s Executive Chairman Bill Ford acknowledged Iacocca’s “central role in the creation of Mustang” and praised him as a “bigger than life” and “one of a kind” figure who “left an indelible mark on Ford, the auto industry and our country.”

— Ford Motor Company (@Ford) July 3, 2019

As history would show, Ford’s loss of Iacocca was Chrysler’s gain. It was Iacocca’s role in the Chrysler turnaround in the ’80s and his charismatic business leadership that made him a media star. His Iacocca: An Autobiography, released in 1984, and his Talking Straight, released in 1988, were bestsellers. He even made an appearance on the hit television series Miami Vice.

Pope John Paul II greets American businessmen, left to right: Bill Fugazy, George Steinbrenner, and Lee Iacocca at the end of his general weekly audience at the Vatican on January 25, 1989. (AP Photo/Arturo Mari)

A January 1987 Gallup Poll of potential Democratic presidential candidates for 1988 showed Iacocca was preferred by 14%, second only to Colorado Sen. Gary Hart. He continually said no to the “draft Iacocca” talk.

In 1982, Iacocca was tapped by President Ronald Reagan to head the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, where he raised over $700 million for the restoration of these American treasures and presided over the renovation of the Statue of Liberty, completed in 1986, and the reopening of nearby Ellis Island as a museum of immigration in 1990.

Lee Iacocca, chairman of the Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., left, meets with New York Mayor Ed Koch at the Waldorf Astoria, on October 29, 1985, New York. The two were there to discuss plans for the July 7, 1986 unveiling of the Statue of Liberty. (AP Photo/Ed Bailey)

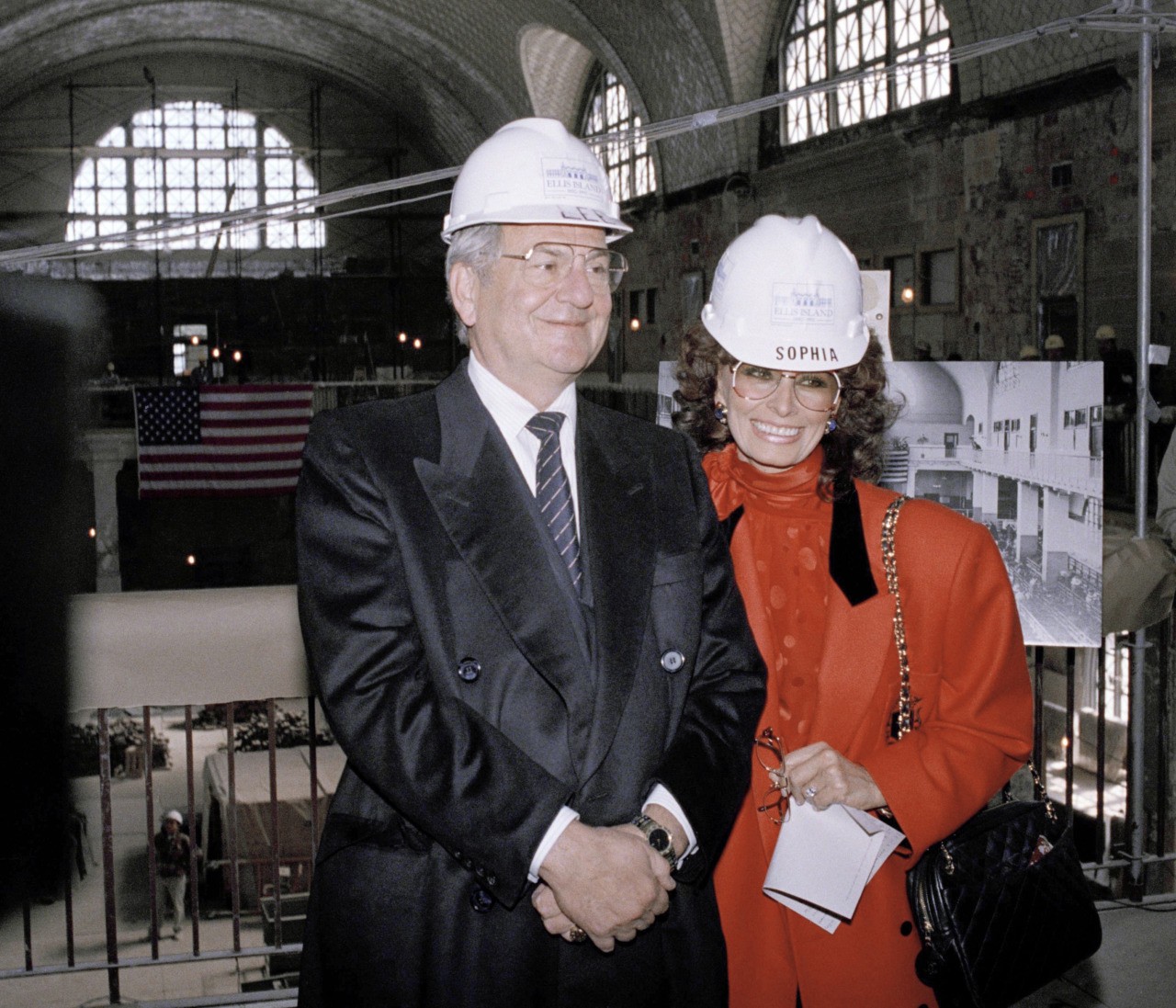

Lee Iacocca, left, and actress Sophia Loren pose in specially monogrammed hardhats at the Ellis Island restoration site, on March 28, 1988, New York. Both made a donation to the Ellis Island American Immigrant Wall of Honor and to the restoration of the islands immigrant museum. (AP Photo/David Bookstaver)

In July 2005, Iacocca returned to the airwaves as Chrysler’s pitchman, including a memorable ad in which he played golf with rapper Snoop Dogg.

Chrysler wasn’t faring well. In his 2007 book Where Have All the Leaders Gone? Iacocca criticized Chrysler’s 1998 sale to Germany’s Daimler AG, which gutted much of Chrysler to cut costs.

As the recession began, sales worsened, and soon Chrysler was asking for a second government bailout. In April 2009, it filed for bankruptcy protection.

“It pains me to see my old company, which has meant so much to America, on the ropes,” Iacocca said.

Chrysler emerged from bankruptcy protection under the control of Italian automaker Fiat. In a 2009 interview with the Associated Press, Iacocca urged Chrysler executives to “take care of our customers. That’s the only solid thing you have.”

Iacocca was also active in later years in raising money to fight diabetes. His first wife, Mary, died of complications of the disease in 1983 after 27 years of marriage. The couple had two daughters, Kathryn and Lia.

Iacocca remarried twice, but both marriages ended in divorce.

The Associated Press contributed to this article.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.