The Congress of Peru voted to oust President Martín Vizcarra on Monday using a constitutional provision that allows it to do so when it deems the president “morally incapable” of running the country.

Peruvians will vote for a new president in a special election in April, to be inaugurated in June.

It is the third Congressional ouster of a president since 2018, when lawmakers prepared to impeach and remove President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, prompting him to quit before he could be fired. That measure made Vizcarra president. In 2019, Congress also voted to remove Vizcarra, but did so after Vizcarra used his powers to dissolve Congress and call for new elections, so the lawmakers did not actually have the power to remove him.

That power struggle left Peru without a clear president for nearly a week as, even among those who believed Congress had the power to remove Vizcarra, disagreements erupted between whether Vizcarra’s vice president or the president of the Congress, the third person in the line of succession, would take over. Ultimately, neither did.

Unlike in the United States, the Peruvian constitution allows for Congress to remove the president without an impeachment trial — simply by vote. Article 113 of the Constitution grants Congress to declare that the president is either physically or “morally” incapable of continuing to execute his duties. Opponents to Monday’s move are demanding the nation’s Supreme Court issue a ruling limiting Congress’s ability to use this provision.

Vizcarra is widely considered a corporatist, center-right politician like Kuczynski, who won a close election against conservative Keiko Fujimori in 2016 to become president. Peru will swear in its new president, lawmaker Manuel Merino de Lama, at 10 a.m. local time Tuesday. As Vizcarra has not had a vice president since his failed removal from power in 2019, Merino, the president of Congress, will take over. Merino is a member of the left-wing Popular Action party.

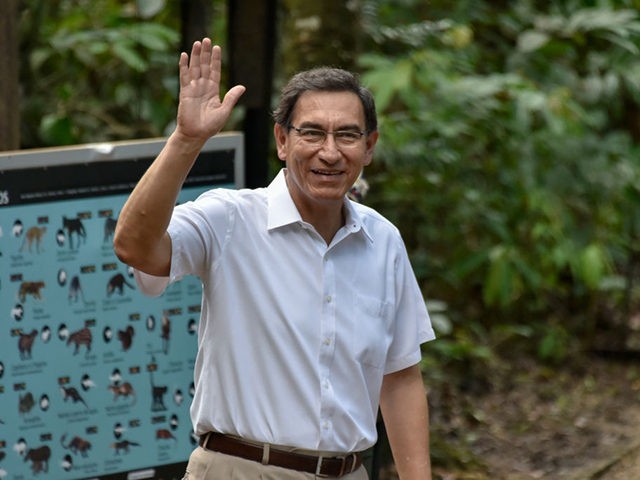

Vizcarra accepted Congress’s decision and went home past midnight on Tuesday, where neighbors welcomed him with applause.

Allegations that Vizcarra, while governor of the department Moquegua, accepted kickbacks in exchange for giving out public infrastructure contracts surfaced in September. A month later, an unnamed “witness” surfaced, speaking to Peru’s El Comercio, stating that the firm Obrainsa-Astaldi paid Vizcarra hundreds of thousands of dollars to secure a public works contract. The accusation was unique in Peruvian politics in that no one accused Vizcarra of taking the money from Odebrecht, a Brazilian contractor believed to have bribed nearly every significant Latin American leader.

Kuczynski’s resignation followed accusations that he took money from Odebrect. His predecessor, left-wing ex-President Ollanta Humala, spent time in prison for allegedly taking Odebrecht money, as did Keiko Fujimori. The president before Humala, Alan García, shot himself in the head in April 2019 when police investigators visited him to discuss Odebrecht-related corruption allegations.

Vizcarra aggressively denied the accusations and claimed that Merino had launched a “conspiracy” to become president.

The accusations did not deter Congress from removing Vizcarra. Peru’s La República, which has branded the removal a “coup d’etat,” reported that the move to oust Vizcarra enjoyed broad support in the legislature. Lawmakers needed 87 votes to push it through; the impeachment received 105 votes from a wide variety of parties. Peru’s government runs on a multi-party system that allows the nation’s wealthy and political factions to rapidly create or destroy many parties as they please. Among the parties voting for Vizcarra’s removal were Popular Force, Keiko Fujimori’s conservative party; the left-wing Popular Action; the Agricultural People’s Front of Peru (Frepap) — simultaneously considered a left-wing populist and Christian conservative party — and the center-right Alliance for Progress (APP). A Frepap spokesperson told reporters on November 2 that its members would not “be part of this political game” to oust Vizcarra.

Only 19 lawmakers voted against removing him. Four abstained.

“First of all, I must say that these are false facts and, secondly, they are uncorroborated,” Vizcarra said in his defense on Monday. “Under no circumstances, regarding accusations of alleged crimes that are still under investigation, can one make definitive decisions — much less vacating the presidency of the Republic.”

Vizcarra also reminded Congress that 68 of its members are facing criminal charges, asking, “do they have to leave their posts, too?”

The accusations against Vizcarra did not allegedly take place during his presidency and are not as well-documented as those against his predecessor Kuczynski, from which he took over after the latter’s resignation. In that case, the conservative Popular Force party, run by Keiko Fujimori, published a video allegedly showing Kuczynski officials trying to bribe Keiko’s brother, lawmaker Kenji Fujimori, to get him to vote for Kuczynski proposals. Kenji Fujimori had recently resigned from Popular Force after reports surfaced that Keiko had taken bribes from Odebrecht.

Kenji Fujimori responded to the video of his alleged bribery by calling its publication “low class.”

The Fujimori siblings are the children of former President Alberto Fujimori, heralded for defeating the Shining Path Marxist terrorist insurgency in the 1990s. The public feud between the brother and sister cost Popular Force a decisive loss in Congress in elections this year that Alberto, convicted of a variety of crimes but serving time at home due to health issues, appears to be attempting to reverse with family photos and claims of unity.

Vizcarra received a warm welcome upon leaving the presidential palace and returning to his neighborhood in the early morning hours of Tuesday. Vizcarra moved his belongings out of the palace immediately after the vote to remove him.

“Obviously I wanted to be there [in power] until the end of the term that the Constitution dictates, through June 28, 2021; despite this, it seems like democracy has been suspended in the dictatorship of votes.”

“Of course it hurts to me, like to all Peruvians,” he lamented.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.