Former Vice President Joe Biden sided with his top donor, the one time credit card giant MBNA Corp., against progressives like Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) on bankruptcy reform during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

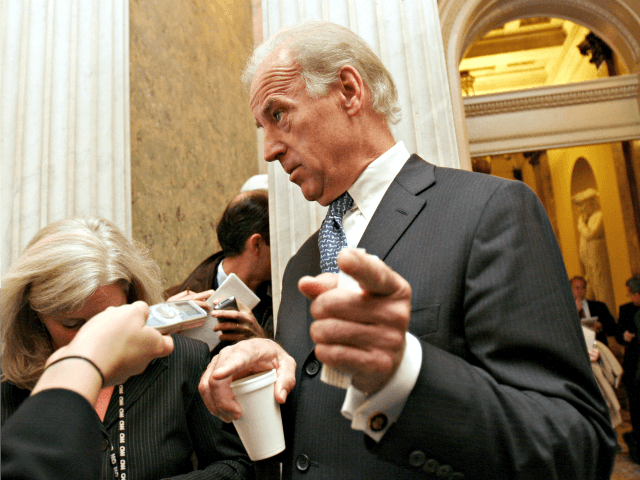

Biden, who has long sought to portray himself as “affable” and “middle class,” has recently come under fire from other 2020 Democrats for his ties to the banking and credit card industries.

Opponents, particularly Warren, have attacked Biden for working to pass the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005. The legislation, which tightened regulations making bankruptcy more difficult, is widely seen to have benefited credit card companies and banks at the expense of consumers. Some have even suggested the law only served to hasten and aggravate the recession of the late 2000s.

Despite the renewed focus, few have drawn lines between Biden’s legislative advocacy and his ties to MBNA, which, prior to its purchase by Bank of America in 2006, was the nation’s largest issuer of credit cards.

Starting in 1996, when Biden was seeking a fifth term representing Delaware in the U.S. Senate, MBNA’s top leadership began donating heavily to his campaign coffers. From 1996 to 2006, individuals employed by the company gave more than $212,000, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. The sum was large enough to make the company Biden’s largest campaign contributor throughout his nearly 40-year career in public office.

The money would not have drawn interest, let alone controversy, if not for the manner and timing of the contributions. In total, more than $63,000 went to Biden between April and October 1996. The total was by far the largest given to any Democrat by MBNA that cycle.

As Byron York detailed in a 1998 widely publicized The American Spectator exposé — titled, “The Senator from MBNA” — the donations arrived in what looked to a be a coordinated pattern.

On April 16 MBNA executive vice-president and chief technology officer Ronald Davies sent in $1,000. Kenneth Boehl, another top executive, also sent in $1,000 on the 16th. And senior vice-president Gregg Bacchieri. And William Daiger, another executive vice-president. And David Spartin, the vice-chairman and company spokesman. The next day, April 17, vice-chairman and chief financial officer Scot Kaufman sent $1,000, as did Bruce Hammonds, MBNA’s vice-chairman and chief operating officer. And John Hewes, senior executive vice-president of MBNA’s credit division. And vice-chairman and chief administrative officer Lance Weaver. On April 18, MBNA general counsel John Scheflen sent in $1,000. On April 20, group president David Nelms sent in $1,000, as did vice-chairman Vernon Wright. On April 22, John Cochran sent in $1,000. So did senior executive vice-president Peter Dimsey. And finally, on April 26, Charles Cawley sent in his $1,000.

York noted a similar pattern emerged after Biden had won his primary campaign that August and was preparing for the general election against a little known Republican. A review of Biden’s campaign finance filings from the time by Breitbart News shows the money flowed mainly in $1,000 increments, the maximum then allowed by Federal Election Commission guidelines.

Since Biden had sworn off political action committees in his bid to pass campaign finance reform, MBNA would have only been able to donate through individuals under its employ. Luckily, as the Wilmington News-Journal reported in 1995, the company already had a protocol in place for exactly such a purpose.

“MBNA Corp. crashed onto the political money scene in 1994 by distributing more than $1 million in campaign contributions, much of it raised through carefully worded memos advising its top executives to give to the bank’s favorite candidates in Delaware and in key races across the country,” the article states.

The memos raised eyebrows among campaign finance experts as they seemed to skirt the limits in place on how much corporations could donate to candidates. MBNA defended its conduct, claiming it had not violated any federal laws or forced its employees to donate against their will. The latter, however, was viewed skeptically, as MBNA had not only requested proof of contributions, but also reasons for refusing to donate.

“The memos were from John W. Scheflen, MBNA’s general counsel,” the News-Journal reported. “He kept records of the contributions and requested confirmation. Instructions read in boldface: ‘Please send me a copy of each of your checks.'”

According to the paper, Scheflen requested in a follow-up memo “to know in writing who wasn’t giving: ‘If you do not plan to make any suggested contributions, I would appreciate it if you would so note.'”

Biden’s 1996 campaign appears to be the first time MBNA made a concerted effort to see him reelected. Despite having relocated its headquarters to Delaware in 1982, MBNA or its employees did not donate to Biden’s campaigns in 1990 or 1984, according to FEC filings. Campaign filings dating back to Biden’s 1972 and 1978 races were not readily available, as the FEC has archived reports from more than 40-years ago.

Even more interesting is that Biden was one of the few Democrats that MBNA favored with its donation. From 1992 until its sale to Bank of America, MBNA and its employees never donated less than 73 percent of their contributions to Republicans. The company’s employees gave more than $575,000 to see President George W. Bush elected in both 2000 and 2004.

Starting in 2000, when Biden took a keener interest in bankruptcy reform, MBNA’s employees began contributing to him regardless if he was on the ballot or not. That year, Biden received more than $69,000 from MBNA, even though he was not seeking reelection for another two years. Similarly, MBNA contributed more than $49,000 to Biden in 2004, albeit he was not on the ballot again until 2008.

Although it is impossible to tell what impact the money had on Biden’s views — especially as he supported efforts to tighten student loan bankruptcy laws throughout the 1970s and 1980s — it is clear that after 1996 he championed MBNA’s legislative agenda with vigor.

In 1999, Biden was one of the lead backers of an initial bankruptcy reform package that held many of the provisions that would eventually end up in the 2005 bill. The legislation was a top priority for MBNA and a conglomerate of other credit card and banking interests.

Biden, along with a cadre of business-friendly Democrats and Senate Republicans, labored to pass the bill in the face of opposition from liberals and consumer advocates. Among those on the opposing side was then-Harvard law professor Elizabeth Warren, a bankruptcy expert who argued the measure favored companies like MNBA over working families.

After an intense back and forth, Biden’s side prevailed and the bill passed in late 2000. It was not signed into law, though, as President Bill Clinton opted to pocket veto the measure on his way out of office.

Biden and his allies were not dispirited, instead seizing the opportunity presented by the incoming-Republican president to pass a bill more favorable to banking interests. They ultimately succeeded in 2005 after MNBA and financial institutions bankrolled an intense lobbying campaign. The following year, the law’s results were evident when bankruptcy filings fell by more than 70 percent across the country.

Although Warren lost the bankruptcy battle in Congress to Biden, she has already signaled an intention to wage it again on the campaign trail.

“At a time when the biggest financial institutions in this country were trying to put the squeeze on millions of hardworking families,” Warren said earlier this year, “Joe Biden was on the side of the credit card companies.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.