For Americans searching for a patriot this Fourth of July, they needn’t look back to 1776. This week will do. On Wednesday, Louis Zamperini, U.S. Olympic track star and World War II hero, died at 97. It wasn’t the first time The Zamp’s obituary had been written.

In 1943, Zamperini crashed into the Pacific on a defective B-24 Liberator ironically sent to find airmen missing in action. Zamperini survived the collision of ocean and airplane along with two others on the eleven-man crew only to face a more harrowing experience lost at sea. He dodged sharks, starvation, drowning, and bullets from a strafing Japanese plane. During this ominous encounter with the skies, a bomb that dropped near the men didn’t explode. As biographer Lauren Hillenbrand summed up his thoughts of that moment of realization, “If the Japanese are this inept…America will win this war.”

When a Japanese boat finally came upon Zamperini and his raft mate–the third passenger had died at sea–the 155-pounder’s weight had descended into the double digits. The pair had drifted 2,000 miles in the open ocean. But 47 days after Zamperini’s ordeal had begun, his ordeal had barely begun.

The Japanese shipped him to a place called Execution Island, which lived up to its billing. The captors at the various camps invariably beat the prisoners of war viciously, forced them into labor, withheld food, mandated silence, and pilfered Red Cross care packages intended for their wards. When the American bombers rolled overhead, a guard nicknamed the Bird brutally rolled the prisoners. When the Olympian begged the Bird for work in exchange for full rations, the sadistic soldier allowed him to clean the pig sty on the condition that he forgo tools. Lauren Hillenbrand explained in her bestseller Unbroken that “he was condemned to crawl through the filth of a pig’s sty, picking up feces with his bare hands and cramming handfuls of the animal’s feed into his mouth to save himself from starving to death. Of all of the violent and vile abuses that the Bird had inflicted upon Louie, none had horrified and demoralized him as this.”

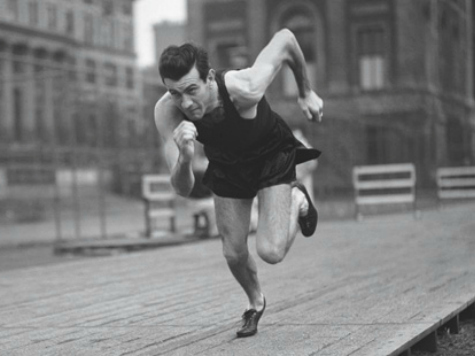

In 1944, after Torrance, California had named an airport for their presumed-fallen son, Radio Tokyo aired a startling message from the former USC track star. The sports hero who had set a collegiate record running a 4:08 mile and competed at the Berlin Olympics channeled his will to win into an indomitable will to live. More than a third of Americans held in Japanese camps died there (compared to about one percent of American prisoners of war in European camps). But a man who persevered for more than a month at sea perhaps stood a better chance than most.

When the war ended, captors and captives switched roles. But the liberated Zamperini still felt imprisoned by his experience. The man who had spent two Independence Days enslaved behind enemy lines and another one dependent on a tiny raft in a giant ocean assimilated poorly into peacetime. He found escape in the bottle to such a degree that his new bride nearly sought escape from the marriage. After Billy Graham issued a challenge from the pulpit, Zamperini traded the bottle for the Bible. “I dropped to my knees and for the first time in my life truly humbled myself before the Lord,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I made no excuses.”

Surely he had plenty from which to draw. A son of Italian immigrants who spoke broken English growing up, a track star cheated by war out of a return trip to the Olympics, a cast away lost at sea, two years a prisoner of war in Japanese camps–Louis Zamperini, on the running track and in life, endured, adapted, and overcame.

Daniel J. Flynn, the author of The War on Football: Saving America’s Game (Regnery, 2013), edits Breitbart Sports.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.