Arguably the first world heavyweight championship bout took place between two Irishmen hailing from such diverse and distant corners of the world as the South End of Boston and Somerville, Massachusetts, now located eight stops from each other on Boston’s Red Line.

“[John L.] Sullivan versus [Long Island-born Jake] Kilrain would be the last bare-knuckle championship fight,” Paul Beston writes in The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled the Ring. Fought under the London Rules—which allowed throws and compelled knocked-down men to resume at the “scratch” in the center of the by-then square “ring”—Sullivan-Kilrain lasted two hours and sixteen minutes under the sweltering heat of the Mississippi sun. “Coming out of his corner to begin Round 44,” Beston informs, “Sullivan vomited in the center of the ring, leading some who knew him well to joke that he had thrown up the tea but retained the whiskey.” The brutality at once explains the illegality of boxing in every state at the commencement of the pugilistic pair’s careers and the presence of Bat Masterson and Luke Short in Kilrain’s corner, which threw in the towel (actually a sponge) at the beginning of Round 76.

Who would voluntarily participate in such savagery?

Hard men who experienced the ring as a respite from the hard lives they endured.

Boxing’s rules evolved. But, as gifted storyteller and expert on and enthusiast of boxing Paul Beston conveys, this one rule of thumb—the kings of boxing wore no crowns before their in-ring coronations—remained.

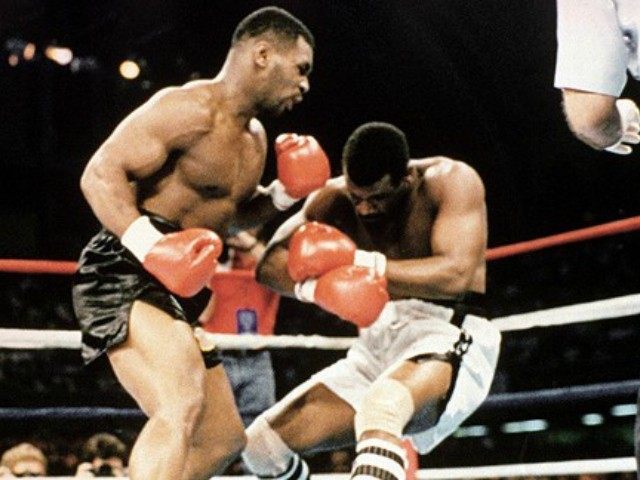

Jack Dempsey, whose hobo haircut under his heavyweight crown advertised an earlier, less glamourous existence on the rails, dropped out of grammar school, left home at 16, and earned his daily bread by entering bars and challenging the local tough in exchange for a vigorish on the bets. Mike Tyson, whose haircut and peekaboo style evoked Dempsey, “never met the man listed on his birth certificate as his father.” He went to reform school at 12, boasted three times the number of arrests as years on earth at 13, and lost his mother at 16. Even the gentlemanly Floyd Patterson, whose fighting style if not his patty-cake power mirrored Tyson’s and Dempsey’s, “became a familiar figure in juvenile courts” and ended up at reform school.

While the bookish Gene Tunney and the chess-playing Ph.D. Vitali Klitschko wore the belt, they proved the exceptions to the rule, next to which appears a picture of Sonny Liston, the illiterate 24th child of a sharecropper who became locally infamous in St. Louis as “the Yellow Shirt Bandit” before becoming internationally famous as the heavyweight champion of the world.

Paupers becoming princes meshed nicely with Horatio Alger stories that made up the stuff of the American Dream. “The champions themselves occupied a public office not unlike the presidency, though they were often better known and better liked than the man in the White House,” Beston writes. Even today, Mike Tyson enjoys greater name recognition than Millard Fillmore and Muhammad Ali’s approval rating certainly bests James Buchanan’s. Americans may struggle to name the current heavyweight champion. But their ability to rattle off a half-dozen champions during the sport’s heyday validates the “when American heavyweights ruled the ring” subtitle of Beston’s book. They still rule our imaginations.

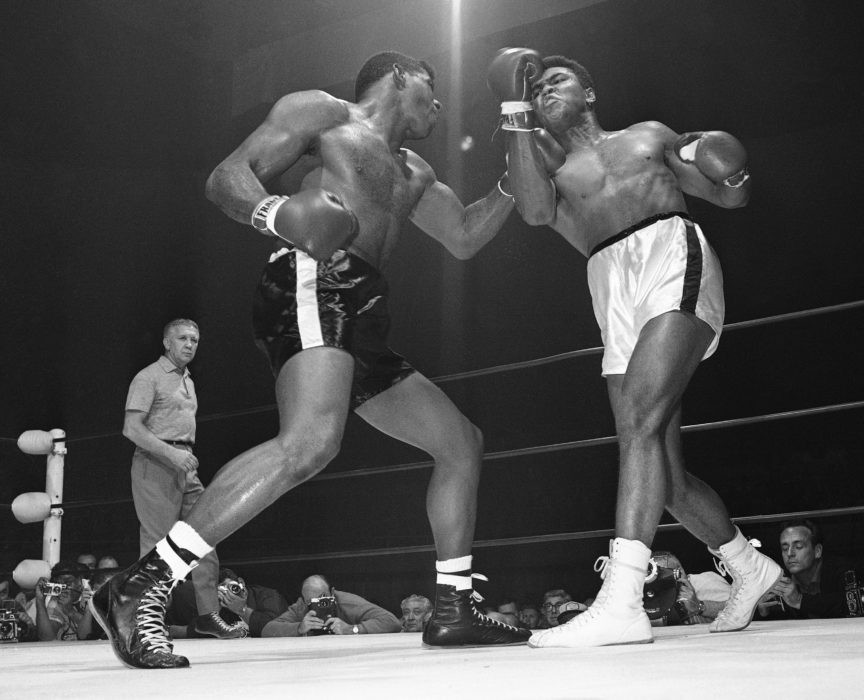

The story Beston tells the story of twentieth-century America through twentieth-century American heavyweights. Jack Sharkey (birth name: Joseph Paul Zukauskas), Rocky Marciano (birth name: Rocco Marchegiano), and other children of immigrants held the most coveted title in sports, mirroring the upward mobility of the children of newcomers. War, which took so much more from others, robbed Army E-6 Joe Louis and conscientious objector Muhammad Ali of prime years of their athletic careers. The lives of Jack Johnson, Ali, and others serve as microcosms of racism and race relations. More so do the nameless African-Americans denied their chance at glory by a de facto ban on them challenging for the title between Johnson and Louis. Tellingly, these two black men gained their glory when foreigners—a Canadian and a German—gave them a shot. But America, and the sport of kings, progressed.

But this is a book about fighters and fights, not war and peace and politics and all the rest. Though Beston understandably devotes more words to three-time champion Ali than, say, flash titlist Leon Spinks, he teaches the reader more about the life and fights of Ezzard Charles, or Larry Holmes or Max Baer for that matter, than one can glean from a Wikipedia entry or a 3 a.m. viewing on ESPN Classic. Who’s the best? Beston wisely ducks a question whose right answers include silence and a shrug but little else. The best, borrowing Rocky Marciano’s toughness, Jersey Joe Walcott’s footwork, Larry Holmes’s jab, Mike Tyson’s explosive power, Floyd Patterson’s hand speed, Jack Johnson’s defensive skills, Muhammad Ali’s ring intelligence, and Lennox Lewis’s physique, does not exist. But, here and there, this guy’s quality or that guy’s skill ranked as the best. What makes the figures examined in The Boxing Kings so compelling, however, are their many flaws and not the few ways in which they appeared perfect.

The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled the Ring, a 313-page chronicling of that golden age of American heavyweights, reads as history of heavyweight boxing that reads as a history of the heavyweight nation claiming the sport’s, and perhaps sports’s, most prestigious title more than any other nation. Between Bob Fitzsimmons and Lennox Lewis, foreigners—most of them among the weakest heavyweight champions in history—claimed the legitimate, lineal heavyweight belt for about seven out of 100 or so years. It was the “American Century” for reasons beyond why Henry Luce dubbed it so.

“With only a few exceptions, all the champions of the twentieth century came from the United States—American kings in the American century,” author Beston writes. “And then, almost right on schedule, when the century passed, so did they.”

Men do not fight in and around Boston as they did in the days of John L. Sullivan and Jake Kilrain. And Americans do not fight all about the globe as marvelously as they did in the days of Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Is today’s frustrating search for the Great American Hope a sign of the United States becoming a land of Eloi or evidence that it no longer sees so many Morlocks in its midst? This Rorschach test of a question tells us more about the answerer than it does about America or boxing.

The Boxing Kings reads like Ali-Frazier III, Holyfield-Bowe I, Louis-Conn, or Dempsey-Firpo (11 knockdowns in five minutes and fifty-seven seconds of violence). The boxing fan, even the sweet science novitiate, cannot look away.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.