Chris Cuomo may have only a middling show on CNN, but he seems destined to be an eternal “winner” in pop-culture mockery and notoriety. Cuomo’s outburst, revealed on August 12, was a little bit newsworthy for its threatened violence; the CNN anchor told another man who had accosted him, “You’re going to have a problem . . . I’ll [bleeping] ruin your [bleep]. I’ll [bleeping] throw you down these stairs.”

Okay, so plenty of people in public life lose their cool in the midst of random confrontations. And no doubt there will be another such incident, somewhere, tomorrow.

Yet what made Cuomo really stand out was his embrace of a particular movie reference, one that hits the funny bone of popular culture. That is, Cuomo got unglued by the comparison of himself as “Fredo,” one of the fictional Corleone brothers in the Godfather movies of 1972 and 1974. To hit the point harder, Fredo was the incompetent, jealous, and, ultimately, treacherous brother. As the character says, helplessly and dishonestly, in the second Godfather film, “I can handle things, I’m smart! Not like everybody says.”

So if we turn from reel life to real life, we can see that Breitbart News’s John Nolte has been gleeful in slapping the “Fredo” label on Cuomo. And obviously, the comparison has gotten under Cuomo’s skin; hence on that video, he is seen yelling at a stranger, as if the volume of his voice will refute the Cuomo = Fredo analogy:

No punk-ass bitches on the right call me Fredo. My name is Chris Cuomo. I’m an anchor on CNN. Fredo is from The Godfather. He was the weak brother.

Defensive, much? As Ronald Reagan, who knew a thing or two about both movies and public life, liked to say, “If you’re explaining, you’re losing.” In other words, in the battle to separate himself from the Fredo trope, Cuomo simply defeated himself.

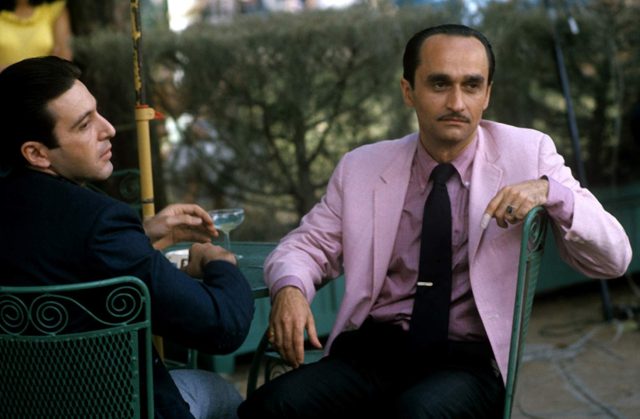

Actor John Cazale as Fredo Corleone. (IMDB)

From a PR perspective, Cuomo dug himself even deeper when he tried to argue that “Fredo” was a slur against Italian-Americans, akin to the “n-word.” That reach of a defense drew heavy fire from Trevor Noah, the African-born host of Comedy Central’s Daily Show. Moreover, other wiseguys pointed out that “Fredo” has been thrown around a lot on CNN, even on Cuomo’s own show—and the host hadn’t objected to this supposed mortal insult. Indeed, Cuomo has even used the reference on himself.

Powered by such delicious hypocrisy, the Cuomo-Fredo meme took on more prominence, aided by butt-kicking tweets from Donald Trump Jr. and Donald Trump Sr. As the President said, “I thought Chris was Fredo also. The truth hurts. Totally lost it! Low ratings.” (The Trump campaign is now even selling a “Fredo Unhinged” tee shirt.)

On August 13, “Fredo” was the number one “Trending in USA” topic on Twitter.

And the following day, the New York Post piled on with a cover, “The Godbother: Chris Cuomo Fury at ‘Fredo’ Insult,” showing a doctored photo of Chris Cuomo, his late father Mario, and his brother Andrew. Mario and Andrew, we might note, were both elected multiple times to the governorship of the Empire State, whereas Chris has his . . . TV show.

In the snarkily triumphant tweet of conservative activist Candace Owens, “I am warmed by the fact that @ChrisCuomo will be known as Fredo in perpetuity.”

Yet beyond the catastrophic optics of Cuomo’s rant, joined by damage-control that did more damage, there’s the interesting question of how it was that the Godfather movies gained so much prominence in our culture, such that so many people would pick up instantly on the Fredo reference.

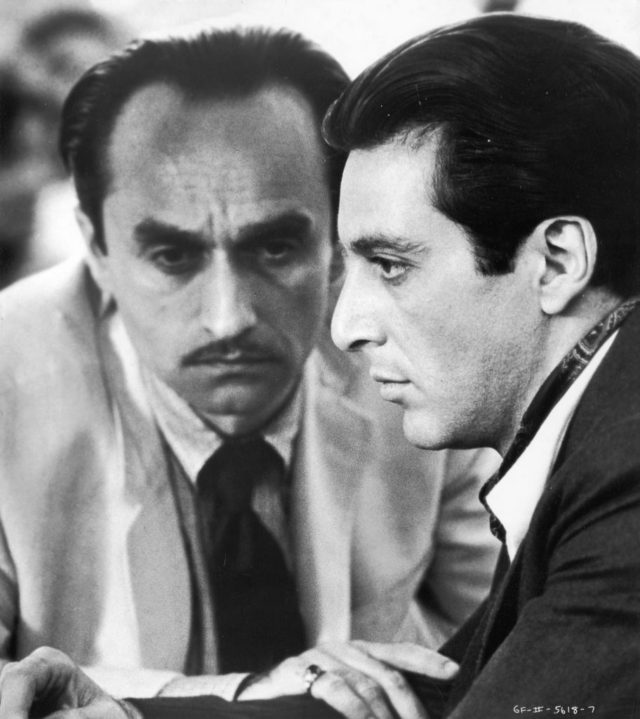

James Caan, Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, and John Cazale. (IMDB)

Back in 1972, The Godfather was a massive hit; the gangster epic was nominated for 11 Oscars and won three—for best picture, best actor (Marlon Brando), and best adapted screenplay. Even in that pre-Internet era, memes from the film flowed fast and furious; for instance, the phrase, “Make him an offer he can’t refuse,” became a common quip, said with humor, or menace—or both. Not coincidentally, the Godfather’s Pizza chain was founded in 1973.

Then, in 1974, along came The Godfather: Part II. It was also nominated for 11 Oscars and won six, including, again, best picture and best adapted screenplay.

John Cazale (left) puts his hand on the arm of Al Pacino in a still from Director Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather: Part II. (Paramount/Getty Images)

Thus the drama of the Corleones had become central to the pop-culture canon; Godfather references and quotes have since abounded, not only around barstools and poker tables, but even at the highest levels of corporate America.

Moreover, Roger Stone, the one-time Trump associate who delighted in sporting gangster-ish suits, made reference to the second film when he suggested to a possible Russia-story witness that he consider Frank Pentangeli, a character who refuses to testify against the mob.

So today, one can go to IMDB.com, find the section on movie quotes—all of them posted by admiring fans—and read practically the entire script of both movies. That’s how popular the films are. (We might note that there was a 1990 sequel, The Godfather: Part III; it was a modest financial success, but an enormous critical failure and cultural disappointment. And so Godfather fans, protective of their treasured cinematic “turf,” generally pretend it doesn’t exist.)

Today, the first two films are so integral to our thinking that they can even be said, in large part, to occupy the psychic space once held by The Iliad and The Odyssey, the classic works of the ancient Greek poet Homer, who is generally seen as the father of Western literature.

In earlier eras, educated people were conversant with the mythical characters from those two epics, including Odysseus, Achilles, and Helen of Troy. Indeed, dutiful students could also how to interpret references to Circe and her sirens, Polyphemus the cyclops, and to Penelope and her suitors.

Yet times change, and people don’t read as much as they once did. But they do watch movies. And so, for better or worse, most people today know more about Vito Corleone, Michael Corleone—and, yes, of course, Fredo Corleone—than about any old Greek protagonist. Folks are more likely to get references to “go to the mattresses” or “leave the gun, take the cannoli” than to such Homeric phrases as “rosy-fingered dawn” and “wine-dark sea.”

Still, for all this change, we can pause to consider that in some ways, not much has changed. That is, there’s perpetual fascination with heroes, great deeds—and, yes, evil deeds.

So while the differences across the millennia are enormous, similarities emerge. Achilles died for honor, and so, too, did Sonny Corleone. Indeed, for the last century, since the 1931 film Scarface, movie audiences have thrilled to the operatic lives, and deaths, of mobsters.

In an influential 1948 essay, “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” Robert Warshow wrote of the gangster genre: “From its beginnings, it has been a consistent and astonishingly complete presentation of the modern sense of tragedy.” And who doesn’t love a sad story, especially if it involves rising to the heights, before sinking to the depths?

Continuing, Warshow added, “In ways that we do not easily or willingly define, the gangster speaks for us, expressing that part of the American psyche which rejects the qualities and the demands of American life.” So we can see that gangsterism, in its lethal immediacy, takes us back, in a fashion, to primal combats—even to, as Homer put it, “the windy plains of Troy.”

And yet gangsterism is more than just carnage; it’s also a style of operating. Gangsters might spend much of their lives in violence, and yet at the same time, they are also conspirators—and conspiracy theories, too, are endlessly popular. That’s why, long before the Godfather movies, leaving aside outright criminal gangs, people spoke of “mafias,” referring to organized groups that may, or may not, be skirting the law—a Kennedy Mafia, a Lavender Mafia, and so on.

As for the Godfather movies of the ’70s, they landed in the wake of Vietnam and Watergate, at a time of rising mistrust of authority, as well as of official explanations. Thus when the films offered a sinister interpretation of such historical topics as the revival of Frank Sinatra’s career in the early ’50s, or the rise of Nevada gambling in that same decade, audiences were primed to pay heed.

So now today, nearly a half-century later, are Americans any more trusting? Are they any more likely to take the word of those in power? As we consider the stinky Jeffrey Epstein case, or the equally stinky case of Harvey Weinstein, or the smell still emanating from the Russia investigation, or from the Catholic Church—should we bestow our trust and confidence in any powerful person? Or in any large institution?

Instead, perhaps, as we navigate these moral swamps, maybe we end up believing that it helps to have some cynical, even conspiratorial, wisdom of our own. After all, nobody wants to be a sucker, or to look like a chump. And so, for inspiration, we might cling to the street-wise wisdom of, say, Tom Hagen, the Corleone consigliere.

Marlon Brando, as Don Vito Corleone, gestures as he sits at a table as colleague and compatriot Robert Duvall, as Tommy Hagen, sits behind him in a scene from The Godfather. (Paramount/Getty Images)

In the films, Tom was always so calm and cool, as well as observing and knowing. So when he whispered in the Don’s ear, as he did so often, we knew he had something sage to say–explaining how things really worked.

So in 2019, even after so much has changed, the Godfather movies are still vital, serving as cynical guides for a cynical age. Yes, they speak to us, with dark wisdom, in this very dark epoch.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.