Mark Levin — author, radio host, executive editor of the Conservative Review, and star and producer of LevinTV — joined SiriusXM host Stephen K. Bannon for the American Revolution Special on Breitbart News Daily.

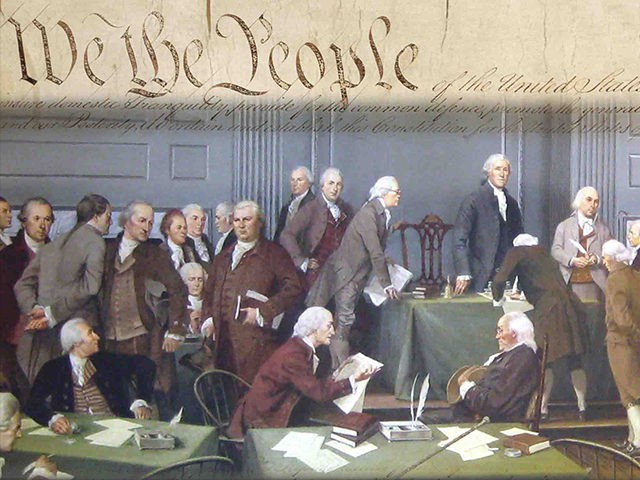

Levin, as a scholar of the Constitution, spoke of how the Founders emerged from the Revolutionary War knowing that a great intellectual and philosophical battle lay ahead. A gathering of warriors, philosophers, and lawyers who were deeply skeptical of centralized government were now tasked with creating one.

“They were very possessive of their state authority, as former colonies, and you can understand that,” he said. “They had these Articles of Confederation, and the Articles of Confederation were fine, except for the fact that the new country was going bankrupt with its war debt. The British, the French, other countries were killing us when it came to trade and so forth, because we had our states fighting with each other — fighting over navigable waters, where they shared rivers, and borders, and so forth, taxing the hell out of their own goods.”

The British were rather literally interested in killing the new country that had broken away for their empire, and as Levin observed, they eventually concluded the time was right for “another bite at the apple,” the War of 1812.

Transforming a loose confederation of states into a functioning nation, without inadvertently creating an autocracy, was a delicate task for men who had inherited John Locke’s fear of centralized power, but Levin said they found inspiration in another philosophical muse, Montesquieu, who had the idea of separating government into three separate and equal branches.

“Madison had a plan, and Sherman had a plan, and others had plans,” Levin said of the Constitutional Convention. “Madison was working behind the scenes, trying to convince Washington and others, because Washington was, in many respects, the great hero. They wanted to convince him that there should be a Constitutional Convention, and he agreed. They wanted him to attend, and be the president of it, and he pretended to reluctantly agree, but he really wanted to do it. He knew his presence there was very important.”

With the esteemed George Washington serving as a quiet referee, a melee between heavyweight philosophers ensued. “They duked it out,” said Levin. “They were creating a brand-new country. They were doing it in secret, but they couldn’t impose it in secret — at some point, the states would have to ratify it. The only state that didn’t send delegates was Rhode Island. It held out to the very, very end. And in the end, the delegates signed off — but not all of them.”

“One of the delegates who didn’t sign off on the Constitution was, of all people, George Mason — one of my favorite of the Founders and the Framers,” Levin said. “He was the architect of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, and he had a lot of say about what was going on. He spoke up a lot about the Constitution. He was the one who argued most vociferously against a listing of rights.”

“People need to understand, the Bill of Rights came later. There was no Bill of Rights, it wasn’t called the Bill of Rights. It came later, at the insistence of the ratification conventions in the states,” he explained.

Levin said Mason voted against the Constitution because “even though he owned slaves, he was an anti-slave delegate, and as much as they tried to resolve that issue there, Georgia and South Carolina threatened to walk out, and they reached the conclusion: ‘Look, we’re not going to have a country here if we try to tackle every single issue, even these big issues. We have to tackle the issues that we can tackle.’”

Clad in heavy wool clothes and wigs, the delegates endured a hot Philadelphia summer in the same building where the Revolution was declared, with some of the same men in attendance. Levin organized them in two camps, the Federalists and Anti-Federalists, warning that the first and most confusing thing to understand about their conflict was that “the Federalists were really the anti-Federalists.”

“The Federalists were pretty good at marketing, because the Federalists were really more the nationalists,” he explained. “The Anti-Federalists — you know, the Patrick Henrys and the Masons, and by the way Monroe, and to some extent Jefferson — they were really the ‘federalists,’ who believed in federalism.”

“They didn’t agree on everything, but they all believed in the notion of individual sovereignty,” Levin stressed. “They all believed that states should have a certain area of sovereignty. I can tell you, as somebody who has studied this his entire life, if the government as it exists today, with an all-powerful Supreme Court, an all-powerful President, Congresses that pass omnibus bills — if that had been up for a vote by the States, it would have been defeated, and it would have been easily defeated.”

“The ratification debates in New York were so brutal, that’s how we got our Federalist Papers,” he said. “Two of them were from New York: John Jay and Hamilton. They started writing essays, as did Madison of Virginia, to persuade the states to adopt the Constitution. New York, the Constitution ratification was expected to lose. Virginia — Virginia! — it was expected to lose. New Hampshire was a close call. Adams and Madison eventually speak to each other, and they say, ‘we’re going to lose this thing.’”

In order to get the Constitution passed, and avoid a fresh round of debates that might have left the convention back at square one, Levin said the delegates agreed that “when the first Congress would meet, they would go back and consider a number of these objections that were raised by the states, and this, in essence, is how we got the First, Second, Fourth, all these amendments to the Constitution.”

The initial crop of seventeen proposed Amendments to the Constitution from the House of Representatives was whittled down to twelve the Senate, of which ten were ratified by the states. Levin cited that process to support his fierce declaration that We, the People “own this Constitution.”

“It belongs to us. It doesn’t belong to the Supreme Court, which has almost no power under Article III of the Constitution,” he pointed out. “The federal appellate courts and federal district courts, they’re not even in the Constitution. They were created by Congress through various judiciary acts. Their jurisdiction is given to them by Congress. Meanwhile, we sit back, and we say there’s nothing we can do when some court issues some decision. Congress can do something. It just won’t do something.”

“When you look at the power of the President, executive orders — the purpose of an executive order is to institute, for the Executive Branch, some statutory requirement or some management requirement. It’s not to be in lieu of legislative activity,” Levin asserted.

“The Supreme Court and the courts have their power,” he continued. “Basically, their power was seized. You have a lot of conservatives who disagree with me, and a lot of liberals for sure, in the Marbury vs. Madison decision which I reject, in 1803.”

In that landmark decision, as Levin described it, Chief Justice John Marshall, “claims essentially that the Supreme Court can get involved in Constitutional issues, and make decisions about Constitutional issues, so where we had implied judicial review, now we have outright judicial review.”

Marbury vs. Madison had “an enormous effect on this country, in terms of what has become, in my view, a judicial oligarchy,” said Levin, noting that Thomas Jefferson would eventually come to view the lifetime appointments of the Supreme Court as the “undoing” of Constitutional order. Levin himself advocates, in his book The Liberty Amendments, that a supermajority of state legislatures should be empowered to overturn Supreme Court decisions.

“The Constitution is inspiring. It is a magnificent document,” Levin pronounced. “And if we would adhere to it fifty percent, even thirty percent, what a different society this would mean, for the better. We have this massive bureaucracy with two million employees, it’s not even in the Constitution. For the most part, that came about as part of the New Deal. We have these all-powerful courts, not only Marshall but Woodrow Wilson talked on, and on, and on — particularly in 1908, before he became President – that real revolutionary change from the Left, from his perspective, was through the courts.”

He pointed to the Supreme Court’s most recent session for more examples of “preposterous opinions that come down, and we’re told to move along.”

“I say hell, no, I don’t want to move along,” Levin declared. “So we need to address it. Our history is full of liberty. It’s full of common sense. It’s full of wisdom. It’s such a special, different country than any other country on the face of the Earth.”

“How many times, anywhere, in any country, any government, would you have a meeting of the men who just won a revolutionary war, trying to figure out how to ensure that nobody has too much power?” he asked. “That’s never happened. It never happens. Usually you’ll get some hunta stepping in, or something like that. These guys met, and they said we have got to figure out how to make sure the purpose of the Revolution, the principles that we have, are enshrined in our governing document, to ensure that we don’t have to go through what we went through before, and to ensure that there isn’t centralized power.”

What they came up with was a system that divided power both vertically and horizontally, with different branches and levels of government holding each other in check. “What’s happening today is, the government is devouring the civil society – exactly what the Framers and the ratifiers rejected,” said Levin.

He likes to contrast the American Revolution with the French Revolution, which he described as “mobocracy.”

“The American Revolution was different,” said Levin. “The American Revolution was about God-given natural rights. The American people, all the way back to the colonists themselves, have always been a beneficent and tolerant people, as we are today.”

The road back from our post-Constitutional society will be a long one, stretching across several generations to come. Levin said he was heartened to see more resources than ever for helping young people appreciate the history and wisdom of the Constitution, thanks to the Internet.

For example, he recommended The Avalon Project, which has many links to important historical documents. He commended historian Pauline Maier’s book Ratification as an excellent narrative about how the Constitution was debated and ratified.

For Levin, the study of the Constitution is a passion, a recreational activity, and a compulsion.

“What kind of a republic is it, where we all sit around, in the early weeks of June, wondering if we have our liberty?” he asked, referring to sessions of the imperial Supreme Court. “What kind of a republic is it, where one man or woman can vote one way, or the other way, and we either have a fundamental right, or we don’t have a fundamental right. Can somebody please point out to me in the Constitution, or anyplace in American history, where such a grant of power is supported? Of course not.”

“We revere the Constitution. We don’t revere what they’ve done to it,” Levin said. “The problem is, tyranny is easy. Liberty is hard. Once liberty is lost, it’s very difficult to get it back, particularly when it’s taken from within by a government – a government that’s supposed to be a republic.”

He warned that it was difficult to fight back against “a government that uses the power of the law to destroy the law.”

Breitbart News Daily airs on SiriusXM Patriot 125 weekdays from 6:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. Eastern.

LISTEN:

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.