“Never get out of the boat.” Absolutely goddamn right. Unless you were goin’ all the way…

Why it’s a left-wing film

With a script loosely based on Joseph Conrad’s novella “Heart of Darkness,” co-writer/director Francis Ford Coppola moves Conrad’s existential tale from the 19th Century African Congo to the 20th Century Vietnam War and portrays America’s involvement there, and our military men in particular, in the harshest and most disturbing ways imaginable. At best, we are forever indifferent to everything and everyone, most especially human suffering. At worst we are murderers of women and children and our government is involved in the kind of secret Black Ops the Left was sure Wikileaks would finally reveal when the just the opposite turned out to be true.

We also epitomize the term Ugly American, treating our South Vietnamese allies like children or as though they don’t exist, and there is no amount of brutality we won’t rain down on our enemies in the North. We are borderline terrorists willing to indiscriminately lay down intense air-strikes on villages where children scramble for cover just so we can surf. We use the dead in ways to strike fear into the hearts of the enemy and casually toss around racial slurs to describe anyone who doesn’t look like us.

Coppola’s monstrous vision of the American military has never been equaled, not even by Oliver Stone. In the realized vision of this great director’s cinematic nightmare, the most terrifying boogeyman of all is The American Presence.

Why it’s a great film

Re-teaming with legendary editor and sound design maestro Walter Murch, in 2001 Coppola added 49-minutes to a new cut of the film that he titled “Apocalypse Now Redux.” Though a respectable and still fascinating and impressive achievement, the added minutes and scenes completely change much of the focus of the original and disrupt the overall intensity. In short, “Redux” is almost an entirely different film and not one I find as compelling. So what you’re reading here are my thoughts on the original, which I consider to be the greatest war film ever made.

My personal theory regarding nothing less than what “Apocalypse Now” is about is frequently laughed at and therefore my own. There’s no one to blame for planting the seed of this idea in my little, fevered mind. Thirty years ago, when I first saw Coppola’s living, breathing odyssey into the dark side of the human condition, I came to believe it and nothing has changed my mind in the dozens of viewings since. So here goes.

At exactly the 7 minute, 33 second mark, — the moment Capt. Benjamin Willard (Martin Sheen) opens the door of his seedy Saigon motel room — I believe we have entered Hell. Not figuratively, literally. I believe that just prior to opening that door, Willard either committed suicide or drank himself to death and has subsequently been sent to Hell for his many, many sins … and he doesn’t even know it.

Everything that happens afterwards, the cold human indifference found in every relationship, the complete absence of reason, and the mission itself — a mission to kill a monstrous version of himself and the only person he’ll connect with on any kind of emotional level — is the eternal Hell Willard built during a life lived in the darkest ways imaginable. The fact that he survives the mission is a major giveaway, but early on in the story, Willard outright admits that this mission given to him was for his sins.

Indeed it was.

This is one of the reasons I prefer the original over the “Redux.” The added minutes and scenes in the later cut tend to the ground the story in something closer to reality. This is especially true for the extended plantation sequence, which declares the story as outright political as opposed to the original, which transcends politics like nothing else. We don’t need to be told the political history of Vietnam or watch the supporting characters nail Playboy Bunnies. This is Willard’s spiritual journey, a journey down river meant to become increasingly harrowing as the characters become more tightly wound and events more bizarre. It feels wrong to interrupt that.

Never get out of the boat, remember?

There’s nothing I can add that hasn’t already been written about the incredible visceral experience of Murch’s Oscar-winning sound design and Vittorio Storaro’s breathtaking cinematography. Coppola’s scoring (with his father Carmine) and especially his use of The Door’s song “The End,” sets a disjointing and ominous tone and feel that remarkably doesn’t relent for any one of the 153-minutes to follow. Forget the story and characters, the look and feel alone of this masterwork works like a drug you won’t shake for days. And even though your better nature tells you it’s not exactly a spiritually healthy thing to do, you do keep going back to get lost in what might be the most successful attempt by any director to transfer the purity of his vision on to film.

John Milius co-wrote the script and you can sense his own special brand of madness throughout., especially in the central characters of Willard and Kurtz (Marlon Brando), two men as indifferent to violence as they are to everyone around them. I’ve read more than one complaint about the third act, after Willard arrives in the personal kingdom Kurtz has made himself a god of in Cambodia, but couldn’t disagree more. Coppola shows enormous faith in his script and his skills as a visual storyteller in building up to this coming confrontation, and the result more than keeps its promise. You don’t want to watch what becomes a full blown horror film set in the depths of human depravity, but you can’t stop. Worse, there is no hope accompanying the death of Kurtz, just the bleak feeling it was all part of a larger plan yet to play out.

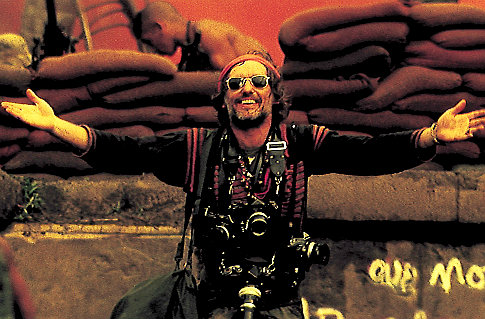

The acting is across-the-board brilliant and almost every scene is a standalone piece of iconography, especially those involving The Mighty Robert Duvall’s Kilgore, an unforgettable and frequently frightening portrait of the ultimate in swaggering charisma and machismo. Just as good is The Mighty Dennis Hopper, who makes the most of a small role as a deranged photographer and disciple of Kurtz. You laugh when you first see him, “I’m an American!”, but that’s only until you realize that his jibberish is really a poetry of black cynicism that comes as close to explaining what’s happening and what hasn’t happened as anything ever will or can.

What really gets under your skin, though is that none of the characters ever bond or connect in any way. Not even the men on the boat. There’s never a single moment of warmth or understanding or relationship growth. As crowded as that boat is, it feels like the loneliest, most emotionally desolate place in the world…

A world without reason, humanity, or logic; a world forever trapped in a cycle of the obscene.

If that isn’t Hell, nothing is.

ADDED: If you want to get a sense for the price an artist pays to bring his vision to life, I can’t recommend the documentary “Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse” enough. If you don’t walk away from this fascinating and frequently cringe-inducing look into the personal toll the making of this film took on Coppola with an understanding that great art doesn’t come easy, then you’re doing something wrong. Anyone who thinks artistic creation at the level of a Coppola just happens or that true artistry doesn’t involve great anguish and isolation, will likely never produce anything close to immortality through their own work… Which might be why they call it “contemporary” art.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.