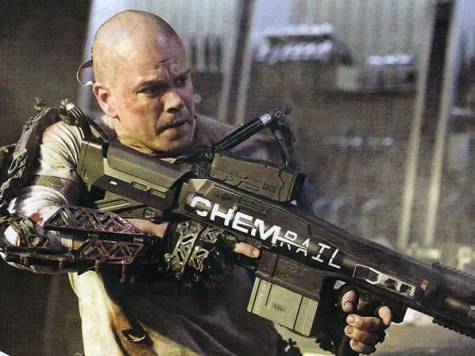

The new movie Elysium, starring Matt Damon and Jodie Foster, is more loaded with liberal politics than an Organizing For America fundraising pitch. It’s more loaded with liberalism than an Ivy League gender studies department. More loaded, even, than an MSNBC roundtable discussion.

Still, it’s a pretty cool movie, featuring an intelligent, if scary, take on the future. And so it merits our attention, because even if one doesn’t agree with its liberal slant, one must realize that liberals have half, at least, of the marbles in American politics–that is, the White House, the Senate, and, of course, the media, of which Elysium is a part.

So if liberals are making noise about something, then conservatives have to think about it, too–if only to react and to combat.

The premise of Elysium is familiar–but updated and special-effected. It’s one of those the-rich-get-richer-while-the-poor-get-poorer stories that Hollywood loves, now moved into the 22nd century. In this film, the rich are not only getting richer, but by the year 2154, they have gotten so rich and so high-tech that they have left the planet. They have ascended to a private wheel-shaped spacecraft orbiting the earth, where they enjoy life in a kind of extraterrestrial Beverly Hills.

Meanwhile, the teeming masses are left behind down on earth–the scenes having been filmed in the slums of Mexico City, to give you an idea of how bad it is–to work in dangerous industrial jobs or to devolve into gangsterism and “Mad Max”-like savagery. The depictions of work are a reminder of what life in 19th century factories was like; as for the depictions of savagery, they are, well, a window into the ways of contemporary narco-trafficking. Indeed, one could compare the Mexico-California drug-gang violence in Oliver Stone’s 2012 film Savages with some of the scenes in Elysium; the earlier film gave the distinct feeling that the brutal future had already arrived.

In Elysium, there are no good rich people, but there also aren’t that many good poor people, either. So this tale shares some elements with the granddaddy of rich-vs.-poor in sci-fi, namely, H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine, published in 1895. In that novella, Wells’ time traveller zooms far into the future, to the year 802,701, where the horrible troll-like Morlocks live and work underground, while the meek, pretty Eloi live and do nothing much aboveground; the catch is that every so often the Morlocks emerge to eat the Eloi. In Wells’ mind, the Morlocks were the stand-in for the oppressed but potentially vengeful proletariat of 19th century England, while the Eloi were the idle rich.

Wells’ point was that oppression would eventually mould the workers into a gnarly and cruel race of beasts, while leisure would eventually turn the upper class into delicate and fragile flowers.

Elysium was made by the South African-born director Neill Blomkamp, who also directed the surprise sci-fi hit of four years ago, District 9, a clever and moving parable of apartheid. Indeed, Elysium is heavy with South Africa-type imagery; there’s even a shot of the South African flag. And since Blomkamp’s class-conscious, liberationist politics seem clear enough, one is left to wonder why he chose to set Elysium so far in the future.

Perceptive critics have already made that point. As Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter notes, the future looks a lot like the now:

The fancy mansions of Elysium and their inhabitants’ wardrobes are exactly what you’d find in Malibu or Miami today, while the rough-hewn down-and-outers sport tats and attitude and would look right at home in a Fast and Furious film.

In other words, if much of the film looks like today, why not set it in today? Or at least sooner than 2154? The dystopic sci-fi classic Blade Runner, released in 1982, touched on many of these same themes, and yet it was set, more daringly, in 2019.

John Nolte of Breitbart News takes the point further, emphasizing that while Hollywood might decry the rich-poor split, Hollywood is actually a part of the problem; perhaps no city in America today better epitomizes that split than Los Angeles. And so what are Angelenos doing about this split, other than trying to profit from it by making movies?

As Nolte observes, if you travel to the flats of LA and look up,

You can see Elysium; and if you squint real hard, you can see the eternally young Matt, Ben, Jack, Brad, Meryl, Julia, and George sitting by shimmering pools, sipping drinks, and using million dollar bills to wipe away socialist tears borne of the horror show playing out below them.

Of course, as almost every interview with a Hollywood type about politics reminds us, as soon as stars delve into the world of policy, they also slip into the realm of hackneyed cliche and self-deluding hypocrisy. Matt Damon, for example, champions the public schools, but sends his kids to private school. So we shouldn’t be surprised in the least that moviemakers make a film decrying inequality, and then go home to their gated mansions and await their profits.

But wait! There’s more–more liberalism! There’s also the film’s sci-fi-y treatment of illegal immigration. Elysium is rife with references to “citizens,” “non-citizens,” “undocumented aliens,” and so on. To drill the point home further, the people on the orbiting space pleasure dome are all white or Asian, while the folks on the ground are mostly Hispanic. And so righteous revolution is inevitable.

The movie’s message is clear: Just as the wretched of the earth must end up sharing the wonders of orbiting Elysium, so, too, the border between Mexico and the US must be opened. No word as to whether or not that open-border policy will include an invitation to stay over at Barbra Streisand’s Malibu estate.

As noted, the earth scenes of “Elysium” were filmed in Mexico City, and they are so, uh, gritty looking that one might say that the movie’s liberal messaging is undercut: Do we really want to open the border and see, for example, Los Angeles or Phoenix or Houston turn into that?

Yet despite the film’s on-its-sleeve liberalism, it offers a weirdly inspiring vision of technological transformation.

Most spectacularly, the orbiting Elysium, seemingly modeled after the “space cylinders” envisioned by the Princeton astrophysicist Gerard O’Neill in the 70s, would be more than cool; they would be a breakthrough for humanity. Yes, even those humans who couldn’t go up to live in space would still benefit, because all of humanity would be better off if we could emancipate ourselves from mere earth.

We might hope that the politico-economic system that builds an Elysium-like orbiter would be more egalitarian and participatory than what’s depicted in the movie, but above all, let’s hope that somebody builds it. It would be great if Uncle Sam were to establish a national colony in space, but if he won’t, then let Richard Branson or Jeff Bezos build an astral hotel or condo–and charge whatever they want for it.

In addition, the film imagines a miraculously effective “re-atomization” machine that rearranges the molecules of those who are sick–or, in one case, those who get their faces blown off. A few seconds under the machine, a little re-atomizing, and all’s well. Is there any basis in real science for such a device? Sure there is, because all scientific invention is based on imagination. And as nano-science, in particular, advances, it becomes all the more easy to imagine a machine that rearranges atoms and thus rearranges the medical problem out of existence. In fact, the proper question should be, why isn’t the government–say, DARPA–working on just that? Maybe it is, of course, and that’s a good thing, because a lot of people here on earth would benefit.

A final point: The film imagines some pretty nifty robots. And once again, one needn’t wait more than a century to see cool ‘bots. The present-day reality is that machines can make machines, and if we can expand that process of self-replication, then scarcity itself will become a thing of the past. Precious metals such as gold and silver might always be scarce, but steel and aluminum are abundant, and in the genius hands of skilled fabricators–human or not–they can be made into life-saving and life-enhancing machines. Ask yourself: Which would you rather have–a gold ingot that just sits there, or a re-atomizer that makes the cancer go away? And we haven’t gotten yet to other inexpensive materials, such as silicon, plastics, and ceramic.

So that’s the irony of Elysium: If we ever reached the point of techno-possibility envisioned in the movie, there won’t be any need for scarcity, because everybody will have a robot, a supercomputer, a 3-D printer–in short, everybody will have plenty. That’s been the lesson of the hundred-fold increase in our global standard of living over the last half-millennium, and there’s no reason that the same increase won’t happen again in the years to come.

Unless, of course, the Hollywood’s precious liberal mentality prevails. In which case, the rich will have a lot, others will have only a little–and somebody will make a movie about it.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.