The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has likely paid millions in American taxpayer funds for nonexistent schools, students, and teachers in Afghanistan, as part of America’s estimated $115-billion ongoing nation-building efforts in the war, reports the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), a watchdog agency.

Meanwhile, in the United States, some schools and universities are suffering major budget shortfalls.

In SIGAR’s report, released Thursday, John Sopko, the inspector general notes:

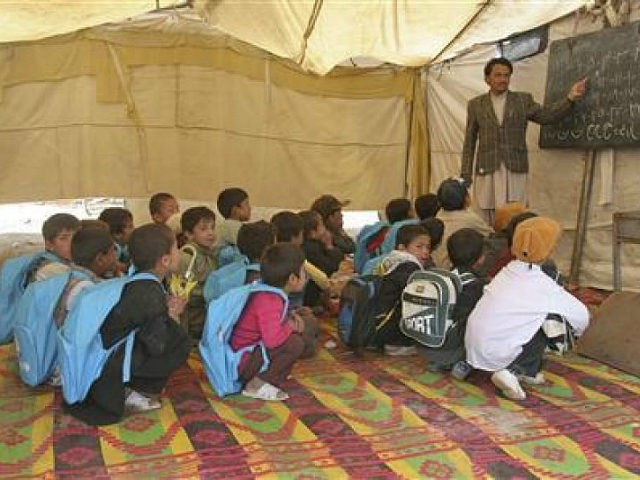

Our observations from these site visits indicated that there may be problems with student and teacher absenteeism at many of the schools we visited in Herat [province] that warrant further investigation by the Afghan government. We also observed that several schools we visited in Herat lack basic needs including electricity and clean water, and have structural deficiencies that are affecting the delivery of education.

On average, SIGAR found that only 23 percent of all students reportedly enrolled have been in attendance and 30 percent of the total number of teachers reportedly assigned have been on-site at each of the 25 schools it inspected in just one province, Herat.

While U.S. watchdog agency officials found only one percent or less of the reportedly enrolled students to be in attendance at four of the inspected schools, it discovered that only 20 percent or less of the teachers reportedly assigned could be found at work at seven schools.

Moreover, the watchdog agency found that one of the 25 schools had been listed as up and running by the Afghan Ministry of Education (MOE), but when SIGAR staffers made a visit to it in the middle day, it had been found to be closed.

Since the war in Afghanistan started in October 2001, USAID alone has spent at least $868 million for education programs in Afghanistan. Despite the endemic and widespread corruption that continues to afflict nearly all components of the Afghan government, the United States has pledged an additional estimated $800 million, part of which is expected to be used on education programs.

SIGAR explains that its finding that “there appear to be extreme discrepancies between reported and observed students and teachers” is based on visits it made to 25 USAID-funded schools in Herat province that lasted between one to two hours.

“While a single site visit, during one of two shifts at a school, cannot substantiate claims of ghost teachers, ghost students, or ghost schools, it does provide valuable insight into the operations of a school on a normal school day,” acknowledges SIGAR.

“Although we cannot draw any firm conclusions based on our observations, because our site visits only represent a snapshot in time, inflating enrollment figures is not without precedent in Afghanistan,” it adds.

Some former Afghan government officials have denied the existence of ghost schools, teachers, and students.

In July 2015, the administration of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani launched a probe into allegations of corruption within MOE.

SIGAR notes, “In January 2016, Afghan media sources began publishing results of the investigation, which included allegations of embezzlement, inconsistent and under-reporting of nonexistent ‘ghost’ schools, thousands of ‘ghost’ teachers on official rolls, ‘ghost’ training seminars, and discrepancies in student enrollment and attendance records.”

The amount of U.S. taxpayer funds distributed to schools across Afghanistan is contingent upon the students enrolled and the teachers employed, among other factors.

“Given that USAID has spent millions of dollars on the construction and rehabilitation of Afghan schools, and continues to spend millions of dollars on teacher training and salaries (through the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund), the agency has a clear interest in ensuring that the improvements it reports in the Afghan education sector are based on actual attendance, rather than on potentially inflated figures,” points out SIGAR.

Despite the nearly $1 billion that the U.S. has spent on the Afghan education system, concerns abound over unqualified teachers, inadequate general education curriculum, students’ lack of access to textbooks, and unbalanced educational services, according to Afghan Minister of Education, Dr. Asadullah Hanif Ba lkhi, notes the watchdog agency.

He noted that Afghanistan’s MOE needs an improved and precise ministry’s management system — the Education Management Information System — used for tracking the number of functioning schools.

The teacher recruitment system, like nearly all components of the Afghan government, is vulnerable to corruption, reported the Independent Joint Anti-Corruption Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (MEC) in June 2015, adding “that the education of Afghan students was being significantly undermined by bribery and nepotism.”

Nonexistent teachers have been a long-standing problem across Afghanistan, noted the MEC report, adding that in most provinces, including the Afghan capital of Kabul, teacher attendance sheets are ignored or frequently forged.

In responding to the report, USAID said, “it is no longer building new schools in Afghanistan and that it had transferred these 25 schools to the Afghan Ministry of Education by 2006,” adds SIGAR.

“A single 1-2 hour site visit during only one of two or potentially three shifts during a school day cannot substantiate claims of low attendance,” argues USAID. SIGAR agrees.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.