This year marks the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta. For many, such as British parliamentarian and best-selling author Daniel Hannan, the anniversary represents “an event of truly planetary significance.” A time when the English people rose up against Norman tyranny to reestablish the freedoms and liberties of their Anglo-Saxon forefathers. A moment that would eventually guarantee the rights of all “freeborn Englishmen” from the tyranny of absolute and arbitrary rule. An event that, up until the last century, was celebrated as reminder that the rights of the individual were superior to the needs of the state and that no man, not even a king, was above the law.

Yet, in 2015, the signing of the Magna Carta will pass with barely a whimper. The primary reasons for this is the claim by revisionist academics and historians that the Magna Carta is nothing more than a myth. That the document did very little for the rights of the common man. That it was nothing more than a struggle between the King of England and the barons who made up England’s wealthy ruling class. They point to the fact that the majority of the barons themselves were Norman and had no interest in the traditional rights of the Anglo-Saxons. That the few rights granted in the Magna Carta to the common people were weak, completely ignored, and discarded before the English people were able to benefit from them. It is, they argue, a fairytale that no longer deserves to be honored. As a result of this revisionist history — inspired by what Cambridge Professor Dr. Alan MacFarlane called “vulgar Marxist interpretations — one of the pivotal points in the age-old struggle against absolute tyranny has been erased from the cultural consciousness of the very people who created it.

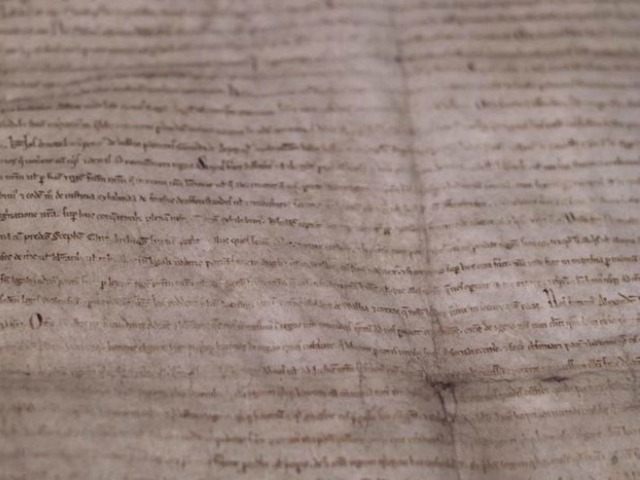

According to Alexis de Tocqueville, the Magna Carta had a ‘magic’ that allowed it to be more than the words scribbled on parchment. He, like most pre-revisionist historians, understood that myths have a uncanny way of developing a life of their own. This is especially true when the myth reflects or symbolizes the ethos of the society. This is exactly what happened with the Magna Carta. As Montesquieu points out, the Saxons whose social and political ethos would come to dominate post-Roman England were “free, and they put such restrictions on the authority of their kings, that they were properly only chiefs or generals. Thus…they never endured the yoke of the conqueror.” They so fiercely resisted tyrannical power that one Roman general was driven to remark that the Saxons fought as if “life without liberty is a curse.”

Whether a Roman general actually made that statement or not is irrelevant. What is relevant is that stories such as these created the ethos that was at the heart of English society at the time of the Magna Carta. That, like their Saxon forefathers, liberty was a birthright of all Englishmen and that no man had the authority to deny them of it. In fact, the ethos was so ingrained into the character of English culture that, by 1215, the barons were culturally more Anglo-Saxon than they were Norman. In today’s vernacular, “they went native.”

In a time when authoritarianism and absolutism would come to dominate Europe, the English regarded their Great Charter as something very unique and extremely special. It reinforced the idea that they were a free people; destined to free themselves from the yoke of tyranny. They understood that only a people dedicated to the philosophy of individual freedom, limited government, representative democracy, and the rule of law could produce such a document in the thirteenth century. This is the “magic” that Tocqueville was thinking of when he wrote:

“They [the English] see the whole English Constitution in it; the two houses; ministerial responsibility; taxation by vote and a thousand other things that are no more there than in the Bible… [Yet] from then onwards a great many men marched under the standard of the great charter without knowing or caring what it had enacted.”

This magic, gave the Magna Carta the power of being a self-fulfilling prophecy. The principles that it came to symbolize would become the foundation of freedom of every English-speaking nation. The ideas it represented would create such monumental documents as the Declaration of Rights of 1688, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution of the United States. Documents that are at the heart of what we consider today to be fundamental human rights.

This is what makes the success of the revisionists to characterize it as nothing more than a power-sharing agreement between elites so tragic. The fact is, while the common people of most of Europe suffered under the servitude and the wretchedness of the poverty produced by absolutism, the ideas encapsulated in the Magna Carta kept economic and political freedom in England alive. This would allow the English-speaking peoples to create the first nation-state, to establish the first modern government, be the first to industrialize, and, with final victory over absolutist Spain and authoritarian France, dominate the world for the next 400 years. Thus, making the rights of Englishmen rights that many people all around the world take for granted as being “universal”.

Power alone did not make Britain and then the United States leaders of the free world. As Rudyard Kipling noted, “any other peoples would have used such power to enslave others.” Guided by the principles of freedom, liberty, and individual rights, Britain would stamp out slavery and its most successful progeny, the United States of America, would go a war against itself to end the scourge of that evil institution. Four hundred years of global dominance by the English-speaking people would usher in an age which would be the most freest and prosperous the in the history of man. No longer would the state of the common man be one of poverty and servitude.

Instead of neglecting the 800th anniversary of the Magna Carta, it should serve as a reminder that the struggle of the individual against arbitrary power has been a long one and it is still not over. We are now halfway through the second decade of the twenty-first century and the forces of tyranny, slavery, despotism and state-ism are once again attempting to exert itself on the free peoples of the world. The English-speaking peoples have always been able to resist the external threats to their liberty, but now we have among us many who insist that freedom and human rights can only be achieved when the individual is subservient to the state. They profess that socialism — or a variant of it — will usher in a new age of freedom, liberty, and equality. On this anniversary it will do us good to remember the words of the Tocqueville when he warned us that, socialism “is a new form of servitude” and that “despotism often presents itself as the repairer of all the ills suffered, the supporter of just rights, defender of the oppressed, and founder of order. Peoples are lulled to sleep by the temporary prosperity it engenders, and when they wake up, they are wretched.”

Avi Davis is the President of the American Freedom Alliance in Los Angeles. John L. Hancock is the author of Liberty Inherited ( CreateSpace,2011) and a fellow of the American Freedom Alliance. They are the co-ordinators of the international AFA conference Magna Carta: The 800 Year Struggle for Human Liberty ( Los Angeles – June 14 -15)

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.