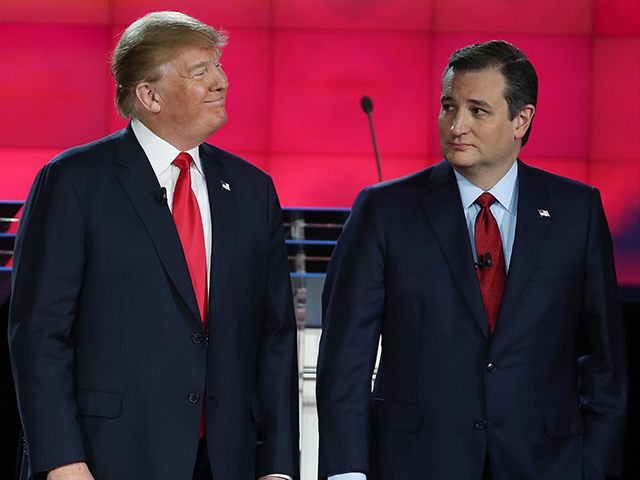

When the votes were finally counted, the Iowa caucus wasn’t that close at all. Texas Sen. Ted Cruz cruised to a 4-point win over national frontrunner Donald Trump and bested late-rising Sen. Marco Rubio by 6 points.

With a record-high Republican turnout in the caucuses, Cruz captured the lead early in the evening and never relinquished it.

The real surprise is that it was surprising at all.

On the day of the caucus, Politico’s “Insiders,” a loose group of political and campaign professionals, predicted that Trump and Clinton would easily win the caucuses on Monday night. A few who thought Cruz could win said his victory margin would be thin.

This is the same group of mandarins who confidently stated last July that Trump had peaked in his race for the Republican nomination.

This wasn’t just a case of political “experts” getting the race wrong, however. The final 13 public polls released in the race all showed Trump leading, some by strong margins. Not one poll released in the final 10 days of the campaign showed Cruz in the lead.

The truly stunning thing about modern polling isn’t that they often get races wrong. It is that they get them unanimously wrong. Simple probablity would suggest that at least a few would get the race wrong in the opposite direction.

Obviously, even the best polls simply reflect a snapshot in time. They don’t predict, they just measure where a race stands at the time the poll is taken.

According to entrance polls taken before the caucus, 45 percent of voters decided whom to support within the last week. This isn’t some aberration. In 2012, 46 percent, and in 2008, 40 percent decided in the last few days.

Late deciding voters is a feature of the Iowa caucus, where voters pride themselves on spending considerable time evaluating the candidates. Inside the caucus, campaigns get to make a final appeal for votes, even before voting starts. It is impossible to quantify, but some people likely change their minds as a result of these appeals.

Because late-deciding voters are a significant block of voters in Iowa, both the Cruz and Rubio campaigns adjusted their tactics accordingly. Donald Trump, however, didn’t seem to take this into account. At several caucus sites, in fact, the Trump campaign failed to deploy surrogates to make a final pitch for the frontrunner.

There are myriad reasons why a campaign wins or loses on election night. Entire political-science departments will pick through the debris of this campaign to glean new insights or observations. Some factors are unknowable, though, and reside in some psychological matrix between voters and candidates. In this particular case, however, there are four clear reasons for Cruz’s massive victory.

2. Evangelicals

The evangelical vote has always been particulary significant in Iowa. In 2008, 60 percent of caucus-goers described themselves as evangelicals. In 2012, 57 percent were evangelicals. On Monday, even more voters, 64 percent, described themselves as evangelicals.

Inexplicably, the public polls of Iowa all significantly undercounted the expected number of evangelicals in the caucus. The final Des Moines Register poll estimated evangelicals would make up 47 percent of the voters. The final Quinnipiac poll put the number of evangelicals in the high-30s. Unsurprisingly, the Register poll had Trump up by 5 points and Quinnipiac had Trump up by 7 points.

Although Cruz was not the only candidate with an appeal to evangelicals — Ben Carson, Mike Huckabee, and Rick Santorum all had support with these voters — he captured 34 percent of their vote, 12 points more than Donald Trump. Cruz actually captured a larger share of the evangelical vote than Rick Santorum in 2012, who faced less competition for those votes.

Trump banked on a high profile endorsement from Jerry Falwell Jr. to help with evangelicals. While he edged out Marco Rubio with evangelicals, after Rubio spent the final days of the campaign talking openly about his faith, the outreach was probably too late for Trump. Cruz had spent months courting this powerful block of voters.

Perhaps the most stunning fact about the size of the evangelical vote is that it dominated a caucus with record turnout. Republican turnout on Monday was 50 percent higher than 2012 and 64 percent higher than 2008. Yet, the share of evangelicals voting actually increased over those two elections.

This flies against conventional wisdom, which assumed that as the number of voters increased, the share of evangelicals would go down. The fact that the opposite happened is a testament to Cruz’s voter targeting operation and ground game.

2. Organization

Even when political insiders were predicting a Trump victory, they acknowledged that Cruz had an impressive ground operation. Countless stories marveled at the data mining, targeting, and ground operation built and employed by the Cruz campaign.

It was the most open secret in all political campaign coverage. It was universally noted that Cruz had the most sophisticated get-out-the-vote effort of any Republican campaign. Ever.

It is odd, then, how much this was dismissed. In post-election autoposies, almost every news organization explained Cruz’s upset as due, at least in part, to his superior ground operation. It is weird this wasn’t really factored in before the votes were cast.

The Trump campaign, in fact, tried to counter the assumption that Cruz had a better organization. The Trump campaign claimed it had a comprehensive ground game, although few saw any signs of it on the ground. The fact that the campaign failed to deploy surrogates to several precincts betrays the weakness of the Trump ground ogranization. To the extent that Trump had a ground effort, it belonged in the last century of political outreach.

In 2008, the media and political commentariat gushed at the data techniques and organization of the Barack Obama campaign. Entire professional careers have been made by individuals who were part of that effort. Cruz’s efforts arguably exceeded even Obama’s campaigns in 2008 and 2012 — technology has progressed after all — yet almost everyone seemed to discount the effort.

While the commentariat was obsessed with media coverage, memes, and narratives, the Cruz campaign went about the grueling work of identifying and turning out its voters. The campaign had developed deep profiles of every potential voter in Iowa, even assigning each a type of Myer-Biggs personality score.

The campaign targeted its messaging accordingly. For example, the campaign had identified 9,131 individuals who were deciding between Cruz and Trump, but not considering Rubio. There were 6,309 voters torn between Cruz and Rubio, but had already ruled out Trump.

In the final days of the campaign, Cruz had switched his advertising from attacking Trump to attacking Rubio. Many in the commentariat guffawed at that switch, but it’s clear Cruz was aware of Rubio’s late surge. The Trump campaign probably owes its second-place finish to Cruz’s late attacks on Rubio.

3. Issues/Values

A big factor in Cruz’s win was that he won one the issues voters were most concerned about. He also won on the “values” issue. Most of the political commentariat dismissed Ted Cruz’s “New York Values” attack on Donald Trump. The media even widely praised Trump’s reponse to the “values” attack at the penultimate GOP debate.

Based on the results, however, the “New York Values” attack was neither a mistake nor an accident. More than 40 percent of caucus-goers said a candidate who “shares their values” is the most important quality in deciding their support. Ted Cruz won these voters 38-5 over Trump. Cruz even beat Marco Rubio on this question by 16 points. More devastating for Trump, however, was that he finished behind even Ben Carson and Rand Paul as the preferred candidate for these voters, almost half the total.

Trump dominated among voters who sought a candidate who would “tell it like it is,” but these voters made up just 14 percent of caucus-goers.

In the final Des Moines Register poll, 56 percent of Republicans said they were bothered by Trump’s past statements on abortion. Even more, 60 percent were bothered by his defense of eminent domain. Cruz ascribed both of these in his messaging as relective of “New York Values.” Keep in mind, these Register poll numbers are from a sample in which evangelicals made up less than half the survey. Among actual voters on caucus night, these numbers are probably higher.

Trump’s line of attack against Cruz was weak by comparison. His relentless attacks on Cruz’s place of birth didn’t register with voters. In the final Register poll, 85 percent of Republicans said it wasn’t a significant issue in their vote. A small fraction of voters said Cruz’s place of birth “bothered” them.

Trump’s insistence on attacking Cruz on an issue that voters didn’t care about gave Cruz the advantage of looking strong against Trump. The national frontrunner had successfully landed blows against every other candidate who challenged him. Attacking Cruz on an issue that didn’t hurt him, though, made Trump look weak.

The top issue for voters was government spending. Cruz bested Trump on this by 8 points and Rubio by 6 points. Terrorism and the economy were tied for second and third most imporant issues. Rubio beat Trump and Cruz on handling the economy, a dramatic swing away from Trump. On terrorism, Cruz beat Trump by 12 points and Rubio by 7 points.

The only issue on which Trump bested his two rivals was immigration. These voters preferred Trump over Cruz by 44-34. Only 10 percent of these voters picked Rubio. Unfortunately for Trump, the immigration issue was a distant fourth in voters’ minds. Just 13 percent of caucus-goers listed immigration as their top concern.

4. The debate

Most of the commentariat praised Donald Trump’s decision to skip the final Republican debate in Iowa. They argued that by skipping the event, Trump attracted more attention and focused attention on media bias against him or other candidates. It is a plausible argument.

Voters don’t really pay attention to all the back-and-forth between candidates and the media. In the Register poll, 46 percent of Republicans said Trump’s decision to skip the debate didn’t matter to them. However, 29 percent said they disapproved, while only 24 percent said they approved.

Voters don’t really care about a larger debate over media strategy or media narratives. They want candidates to compete for their vote. Around the same time that Trump decided to skip the debate, he joked that his supporters would stay loyal to him, even if he murdered someone in the middle of Manhattan.

Obviously, Trump’s statement was a joke. It was, at best, ill-timed however. Coming just days before he decided to skip the final debate created an easy impression of someone who was taking his lead for granted. In the final week, Trump was clearly growing his support in the polls, as evidenced by 13 polls showing him with a lead.

With 45 percent of voters making up their mind after most of those polls had been complete, though, the decision to skip the debate can’t be said to have helped him. At the very least, it provided more oxygen to both Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio at the exact moment voters were making up their minds.

Even if skipping the debate didn’t hurt Trump in the traditional sense, it provided a late boost to Rubio at exactly the right moment for his campaign. Rubio’s strategy was built on a late surge in the state. He almost rode it into second place.

As the campaign moves now to New Hampshire, most pundits will recalibrate their political expectations. Cruz’s win, they will argue, is unique to Iowa because of its heavy presence of evangelicals.

A sophisticated data and ground operation is not unique to Christians, however. They same tools can be employed to target and turn out voters in any state. Obama did this successfully in both 2008 and 2012.

In the end, Cruz’s victory was built on old-fashioned political organizing. At it’s heart, politics is still an old-fashioned business, built on one voter contact at a time.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.