The mainstream media’s verdict is in: Reporters want everyone to be happy that the Jones Act has been suspended for Puerto Rico, in the wake of Hurricane Maria.

The Jones Act—formally, the Merchant Marine Act of 1920—is aimed at bolstering U.S. shipping, by requiring that cargo between U.S. destinations be carried on American-made ships with American crews.

To some, that might seem like an innocuous requirement—Buy American. However, to the self-styled “best and brightest,” Buy American is a gross violation of globalist, free-trade principles. And so even if the Jones Act helps American ship-owners and American workers, well, to the elite mind, that’s not a worthy consideration—and, in fact, to some, maybe that’s even a good argument against Jones. (Most workers, after all, voted for Donald Trump.)

Reflecting, as always, elite opinion, the MSM has led the anti-Jones Act stampede. Here’s just a sample: An opinion piece in The New York Times: “The Jones Act: The Law Strangling Puerto Rico.” The author of that op-ed went on to label Jones as “a shakedown, a mob protection racket.” (Needless to say, the Times did not run a piece reflecting the pro-Jones side.)

Meanwhile, speaking for the D.C. Beltway, The Hill printed its demand: “Lift the Jones Act.” And US News & World Report argued that the right solution is not just a waiver, but to “repeal or substantially reform the Jones Act.”

President Trump was obviously influenced by this anti-Jones onslaught. Oh sure, for a few days after Maria, he hesitated. As he said on September 27:

A lot of people that work in the shipping industry … don’t want the Jones Act lifted.

But Trump’s resolve didn’t last long, as the pressure kept coming. “Trump is wrong to defend the Jones Act,” snapped The Washington Examiner. As The Los Angeles Times put it on the following day, “Trump has faced criticism that he had not done enough to help provide relief to the battered island”—and the Jones Act was, as always, included in the list of anti-Trump particulars.

Meanwhile, others in the MSM were doing their best to turn Maria into Trump’s Hurricane Katrina, that being the 2005 storm that hit New Orleans and undercut George W. Bush’s presidency. As MSNBC chortled, Trump faces a “Katrina Moment.” So the administration evidently felt that it had to give way—so goodbye, Jones, at least for now.

On September 28, the administration announced that it would agree, after all, to a Jones Act waiver, so that foreign ships, and foreign crews, could deliver cargo to Puerto Rico. Whereupon Slate bannered this snarky headline, communicating the MSM’s attitude of exasperated triumph: “Trump Finally Waives Jones Act to Allow More Aid Shipments to Puerto Rico.” [emphasis added]

So what’s the deal with this Jones Act?

The Merchant Marine Act dates back to 1920, when it was spearheaded by Sen. Wesley Jones (R-WA), as a way of boosting U.S. shipping.

Jones wrote the legislation in the wake of World War One; during that epic conflict, of course, getting men and cargo across the Atlantic was critical, and yet German U-boats had sunk nearly 5,000 U.S. merchant ships, totaling some 12 million tons.

The lesson was clear: America needed a better anti-submarine warfare capacity, of course, but it also needed, pure and simply, plenty of cargo ships to withstand the attrition of combat.

The Jones Act is forthright in addressing the cargo-ship issue. As the legislation declares in its preamble:

It is necessary for the national defense and the development of the domestic and foreign commerce of the United States that the United States have a merchant marine: (1) sufficient to carry the waterborne domestic commerce and a substantial part of the waterborne export and import foreign commerce of the United States … (2) capable of serving as a naval and military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency; (3) owned and operated as vessels of the United States by citizens of the United States.

Those points were plenty persuasive at the time. In fact, the Republican majorities in both houses of Congress agreed with Jones, and on June 5, 1920, a Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson, signed the bill into law.

Yet ever since, free-traders have hated it. “Sink the Jones Act” was the Heritage Foundation’s headline in 2014. And the following year, the Cato Institute, too, joined in the Jones-trashing. And these were only some of the latest volleys in nearly a century’s worth of anti-Jones volleying.

Finally, in the wake of Maria, the anti-Jonesers saw their opening. Sen. John McCain, always a globalist and long a critic of the law, teamed up with Rep. Nydia Velázquez (D-NY) and others in Congress to demand the waiver, allowing foreign ships to enter the market. As we have seen, they got what they wanted.

So is that all there is to the story? Are we to conclude that the Jones Act was a bad idea whose time has finally ended?

One who strongly disagrees is Rep. Garret Graves, Republican from Louisiana. As Graves told The New Orleans Times-Picayune, “This is a solution in search of a problem. There are several thousand shipping containers sitting at the docks in [Puerto Rico] today.” In other words, the problem isn’t a lack of shipping to Puerto Rico, it’s a lack of distribution capacity within Puerto Rico.

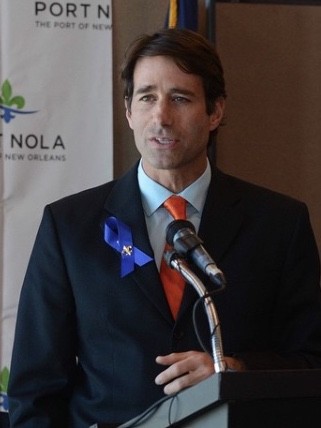

Rep. Garret Graves (R-LA) speaking at the Port of New Orleans.

Graves added:

The problem isn’t the Jones Act. The problem is that there was a hurricane. Logistical systems are destroyed. Trucks, highways and other transportation systems are gone. They can’t get food and supplies to hurricane victims.

Continuing, the Pelican State lawmaker declared:

Anyone [who] thinks this waiver just solved the problem is confused. I’d argue that it just did more harm than good. We have a huge shipping industry on the Gulf Coast that needs the jobs and economic activity now to help economies recover from their disasters. You just took American jobs and sent them overseas. [emphasis added]

So that’s the real story: The globalist forces are using the disaster in Puerto Rico—a disaster that’s one-part the result of the hurricane, one-part the result of an an antiquated and overwhelmed infrastructure, and perhaps, too, as Trump has said repeatedly, as recently as September 30, one-part the result of local incompetence—as an opportunity to get what they’ve always wanted, namely, an end to the Jones Act.

As an aside, we can observe that this is a familiar pattern. That is, the elites are usually in favor of crushing the rights of working people, because, well, that’s how elites prove that they’re the boss.

Yet the purpose of a nation is not to slake the ego of its upper-crust grandees. Instead, the first purpose of a nation is to survive. And that’s where the Jones Act comes in, because the idea behind it—American ships, with American crews that can be called into service to America if need be—is a key part of U.S. national security.

Indeed, loyal ships and loyal crews are a key part of any seafaring nation’s defense. And there’s no need to take Virgil’s word for it; we can look to world history.

In Britain, for example, a Jones Act-type law was on the books as far back as 1381. Once again, the logic was both simple and inescapable: Britain’s security was dependent on its seafaring capacity, and a domestic merchant marine was a crucial capacity-builder, in terms of both ships and, just as importantly, trained crews.

Interestingly, one Briton who agreed with this argument was the economist Adam Smith, author the famous 1776 tract, The Wealth of Nations. Smith is typically remembered as a free-trading libertarian ideologue—remembered that way, of course, by free-trading libertarian ideologues.

Yet in fact, Smith was a nuanced thinker who cared about, more than anything else, the expansion of British wealth and power.

In Smith’s view, free trade was a tactic, not an end in itself. That is, Britain should use free trade when it was to its national advantage, and not use it, otherwise. (The free traders, of course, choose to overlook the frankly protectionist component of Smith’s thought.)

In fact, within pages of The Wealth of Nations, Smith praised the Navigation Act of 1650, as well as similar proto-Jones Act-type laws passed by Parliament, for the simple reason that British security required them. Free trade was a nice theory, but Britain’s safety was nicer. In his words:

As defense, however, is of much more importance than opulence, the Act of Navigation is, perhaps, the wisest of all the commercial regulations of England.

So we can see: It’s good to be rich, but it’s better to be safe. And safety requires a robust maritime capability.

Some might argue, of course, that the world has changed since Adam Smith’s time, or since the time of Sen. Jones. That is, nowadays we have airplanes, and drones, and computers and whatnot, so why worry about clunky old ships? Why worry about “old” transportation when we have new transportation—even cyber-virtualization?

Yet as long as there are oceans, navies will need ships to patrol them. One outfit that has learned that the hard way is our own U.S. Navy. As we all know, the Navy has suffered a series of humiliating and tragic accidents of late, including, just this year, two mid-sea collisions that left 17 sailors dead.

Only now, the Navy has discovered, to its horror, that it lacks the sort of deep technical competence needed to keep its vessels safely afloat. In the words of one sea salt, former Navy surface officer Steven Stashwick, today’s fleet suffers many challenges, including overwork and underfunding. And yet, he concludes, the ultimate problem is that not enough sailors know how to be good sailors:

Beneath these issues are more long-standing factors that have left the surface fleet’s officer corps proficient as warfighters, but lacking in skill as professional mariners. [emphasis added]

To its credit, the Navy itself has absorbed the lessons and is once again focusing on basic seamanship; in fact, to get its navigation right, it’s going back to old-fashioned pencils and compasses. Thus we are reminded: Some times, the old way is still the best way.

In the meantime, the rest of us can observe: The teaching of essential seamanship, of course, is the natural result of having American crews on American ships—just as the Jones Act has always intended. That was an important principle in 1920, and it’s just as important a principle in 2017.

Okay, so one last point: If we were to keep the Jones Act because our national security requires it, then what should we do about the disaster Puerto Rico, or any similar domestic disaster in the future? The answer, of course, is that we should always be ready to safeguard our fellow citizens by doing whatever it takes—whether it be direct relief in the wake of a disaster, infrastructure rebuilding, or direct logistical coordination in the moment of a crisis. That’s the way of a strong nation: Its citizens have each other’s backs. And so if it costs a little more to do it right, well, we should pay a little more and do it right.

Thus we can see: The Jones Act is part of the solidaristic mutuality that all of our citizens—including our fellow citizens in Puerto Rico—very much need. What Ben Franklin said three centuries ago is still true in its blunt truth: If we don’t hang together, we could all hang separately.

If the Jones Act were in place, as it should be, we could help the people of Puerto Rico without hurting Rep. Graves’ constituents in Louisiana, and all the other hard-worker seafarers in the U.S., as well as our essential shipping capacity.

This is a rich country: In times of disaster, we can afford to take care of our own, while not sacrificing the working wages of our own—or the safety of all of us.

And that’s why we need the Jones Act.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.