WASHINGTON, DC – The Supreme Court unanimously ruled on Wednesday that the Constitution’s protection against excessive fines blocked Indiana from seizing a high-end vehicle, but Justice Clarence Thomas would have reached the same result by another route, with Justice Neil Gorsuch signaling support for Thomas’s originalist argument.

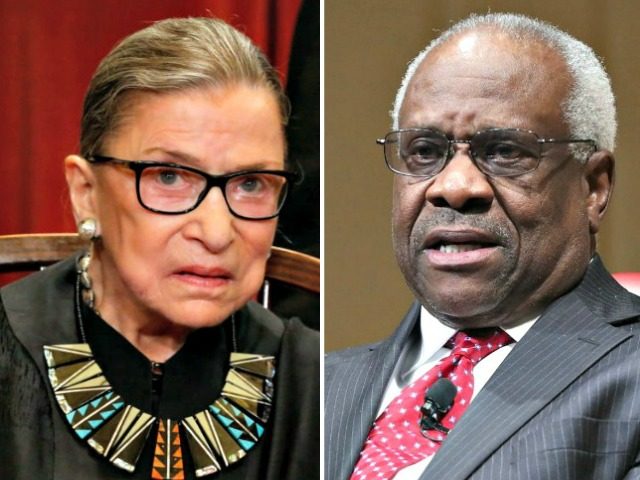

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg wrote the opinion for the Court, summarizing the facts as follows:

Tyson Timbs pleaded guilty in Indiana state court to dealing in a controlled substance and conspiracy to commit theft. The trial court sentenced him to one year of home detention and five years of probation, which included a court-supervised addiction-treatment program. The sentence also required Timbs to pay fees and costs totaling $1,203. At the time of Timbs’s arrest, the police seized his vehicle, a Land Rover SUV Timbs had purchased for about $42,000. Timbs paid for the vehicle with money he received from an insurance policy when his father died.

The Constitution’s Eighth Amendment provides, “Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” It applies only against the federal government.

But that middle part, called the Excessive Fines Clause, would be relevant here if that right applies against state and local governments through the Fourteenth Amendment, because the maximum fine under the Indiana law is $10,000, yet the Indiana Supreme Court allowed seizing a $42,000 vehicle as punishment.

Ginsburg wrote for eight of the nine justices that:

… the protection against excessive fines guards against abuses of government’s punitive or criminal- law-enforcement authority. This safeguard, we hold, is fundamental to our scheme of ordered liberty, with deep roots in our history and tradition.

“The Excessive Fines Clause is therefore incorporated by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,” the Court held, and then delved into history to justify its holding.

The Court noted that the concept of fines not being too large goes all the way back to Magna Carta in A.D. 1215, where the English adopted as a rule of law that economic sanctions “be proportioned to the wrong” and “not be so large as to deprive an offender of his livelihood.”

The concept eventually ended up in the English Bill of Rights of 1689, which included in relevant part, “excessive Bail ought not to be required, nor excessive Fines imposed; nor cruel and unusual Punishments inflicted.”

Ginsburg noted that this English concept also ended up in several legal provisions in the laws of eight states when the Constitution was adopted, including Pennsylvania.

“The State of Indiana does not meaningfully challenge the case for incorporating the Excessive Fines Clause as a general matter,” she continued, essentially complimenting Indiana Solicitor General Thomas Fisher with understanding that the right definitely applied against the states, and just trying to find a narrow ground for victory for Indiana. “Instead, the State argues that the Clause does not apply to its use of civil … forfeitures because, the State says, the Clause’s specific application to such forfeitures is neither fundamental nor deeply rooted.”

The Court sent the case back to the Indiana Supreme Court for rehearing.

Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote a concurring opinion that should excite conservatives, acknowledging more than a century of Supreme Court precedent but adding that the Constitution’s original public meaning would reach the same result through a different route:

The majority faithfully applies our precedent and, based on a wealth of historical evidence, concludes that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the Eighth Amendment’s Excessive Fines Clause against the States,” wrote Gorsuch. “As an original matter, I acknowledge, the appropriate vehicle for incorporation may well be the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause, rather than, as this Court has long assumed, the Due Process Clause.

“But nothing in this case turns on that question,” he continued, possibly suggesting that he might have voted differently if the right in question could be claimed by U.S. citizens in a way that foreigners could not.

“Regardless,” Gorsuch concluded, “there can be no serious doubt that the Fourteenth Amendment requires the States to respect the freedom from excessive fines enshrined in the Eighth Amendment.”

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote separately, quoting heavily from his concurring opinion in McDonald v. Chicago, the 2010 case that extended the right to bear arms to the states. Taking an originalist approach, he began:

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” On its face, this appears to grant . . . United States citizens a certain collection of rights—i.e., privileges or immunities—attributable to that status. But as I have previously explained, this Court marginalized the Privileges or Immunities Clause in the late 19th century by defining the collection of rights covered by the Clause quite narrowly. Litigants seeking federal protection of substantive rights against the States thus needed an alternative fount of such rights, and this Court found one in a most curious place—the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, which prohibits “any State” from “depriving any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

“Because this Clause speaks only to ‘process,’ the Court has ‘long struggled to define’ what substantive rights it protects,” Thomas continued. The Supreme Court over the years had invoked substantive due process to invent various rights not found in the Constitution, like the right to abortion.

“Because the oxymoronic ‘substantive’ ‘due process’ doctrine has no basis in the Constitution, it is unsurprising that the Court has been unable to adhere to any guiding principle to distinguish ‘fundamental’ rights that warrant protection from nonfundamental rights that do not,” Thomas reasoned.

“And because the Court’s substantive due process precedents allow the Court to fashion fundamental rights without any textual constraints, it is equally unsurprising that among these precedents are some of the Court’s most notoriously incorrect decisions,” he observed.

Thomas cited Roe v. Wade as an example of a notoriously incorrect substantive due process decision. He also cited Dred Scott, the 1857 case where the Supreme Court held that black people are not U.S. citizens and therefore that federal courts lack jurisdiction to hear their cases.

Dred Scott is widely considered the original substantive due process case, and is among the most infamously wrong decisions ever handed down by the Court.

Thomas then pivoted to the Excessive Fines Clause, making the case for why it applies to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause, rather than the Due Process Clause.

“For all the debate about whether an explicit prohibition on excessive fines was necessary in the Federal Constitution, all agreed that the prohibition on excessive fines was a well-established and fundamental right of citizenship,” Thomas began.

“The prohibition on excessive fines remained fundamental at the time of the Fourteenth Amendment. In 1868 [when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified], 35 of 37 state constitutions expressly prohibited excessive fines,” he continued.

“The right against excessive fines traces its lineage back in English law nearly a millennium, and from the founding of our country, it has been consistently recognized as a core right worthy of constitutional protection,” added Thomas. “As a constitutionally enumerated right understood to be a privilege of American citizenship, the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition on excessive fines applies in full to the States.”

Justices who say that provisions from the Bill of Rights apply to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause can still do so through a principled lens. Justice Samuel Alito has repeatedly demonstrated a profound commitment to the rule of law, yet wrote that the Second Amendment applies to the states through due process. Alito relied upon the doctrine of stare decisis, recognizing that the Supreme Court had been applying rights through the Due Process Clause for more than a century, and concluded that the Second Amendment should be treated no different than the First Amendment in that regard.

However, Thomas was alone when he mentioned the Privileges or Immunities Clause in 2010. Now there are two out of nine discussing it. Thomas is gaining ground regarding a constitutional provisions with broad implications for constitutional rights.

The case is Timbs v. Indiana, No. 17-1091 in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Ken Klukowski is senior legal editor for Breitbart News. Follow him on Twitter @kenklukowski.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.