On Monday, an angry mob of vandals sought to pull down the famous equestrian statue of Andrew Jackson, our seventh president, from its place in the center of Lafayette Square, just across Pennsylvania Avenue from the White House.

The mob also wants to create an “autonomous zone,” modeled after the one in Seattle—except that this will be called the “Black House Autonomous Zone.” Of course, if such a “BHAZ” were ever to be created, President Jackson would have to go.

Protesters attempt to pull down the statue of Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Square near the White House on June 22, 2020, in Washington, DC. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

Fortunately, on the night of June 22, the D.C. police protected the statue and prevented the creation of any such BHAZ. Although we might note that in days past, the statue had been spray-painted, as have all the other statues in the square, dedicated to a quartet of foreign-born heroes of the American Revolution: France’s Marquis de Lafayette and Jean de Rochambeau; Poland’s Tadeusz Kościuszko; and Prussia’s Baron Frederich Wilhelm von Steuben. (These four men risked everything to sail across the Atlantic to help liberate the colonies.)

Yet in the middle of those four greats is an even greater figure, the American Andrew Jackson. Old Hickory, as he was known, earned his accolades the hard way: as a volunteer patriot, as a war hero, as a political leader, and as a staunch champion of American sovereignty.

Born in South Carolina in 1767, he joined the American Revolution at age 13. Later, he moved to Tennessee and was elected to the U.S. Senate. And when the War of 1812 erupted, he led an army of volunteers—Tennessee is known, of course, as the Volunteer State—to defend Louisiana. Over the next three years, in the swamps and bayous, Jackson’s men fought both the British and their Native American allies.

Then on January 8, 1815, Jackson led his troops in America’s greatest victory of the war, the Battle of New Orleans. (That feat of arms was later recalled in a song by Johnny Horton, “The Battle of New Orleans,” which rose to #1 on the Billboard chart in 1959.)

The Battle of New Orleans by painter Edward Percy Moran (1910). General Andrew Jackson is shown standing on the parapet of his defenses as his troops repulse attacking Highlanders. (Wikimedia Commons)

After that military triumph, Jackson became a national hero. Appointed as a commanding general by President James Monroe, and then as territorial governor of Florida, he led Americans to victory again in the First Seminole War.

And here we might pause over an historical criticism that’s always raised about Jackson: that he was an “Indian fighter.” And it’s true, he was indeed. And so for that fact alone, many among the Woken would “cancel” him. Yet if we think about Jackson’s actions in the context of his time, they are vastly more justifiable than they have been made out to be in today’s politically correct school textbooks.

In the early 19th century, the North American continent was occupied, not just by Americans, but also by the British in Canada, as well as the Spanish in Florida and most of the American West. Meanwhile, the French were lurking around too, operating from bases in the Caribbean.

Also, let’s not forget the Russians, who had already colonized Alaska and were working their way down the coastline of the Pacific Northwest. Later in the 19th century, other countries, too, including Germany and Japan, would go nosing around America. And why not? It was valuable territory, and so if the Americans hadn’t filled the vacuum, other nations would have. (For all the difficulties we are having today, they would be unimaginably worse if we had been sharing this continent with rival, even hostile, powers these past few centuries.)

In the complicated geopolitical mix of Jackson’s time, Native Americans were sometimes on the side of the Americans and sometimes on the side of foreign rivals. Thus, the general policy of the United States throughout the 19th century was to clear away those Indian tribes that were hostile to white settlement. This clearance policy extended into and after Jackson’s presidency with Congress’ passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830. That act led to the forced relocation of some 60,000 Indians from the Southeast to places further west, most notably Oklahoma territory, in an event that became known to history as the “Trail of Tears.” Interestingly, many of the native tribes actually owned African American slaves and took them with them on the forced trek west.

Is such a relocation policy tolerable today? Of course not, just as slavery imposed by anyone is not tolerable. However, the world was different then—and in any case, we should learn history first and then judge it. After all, if the violent simpletons of today win, we’ll be left with nothing; that is, we’ll be left with nothing to guide us, nothing to inspire us, nothing even to resolve never to repeat.

In the context of the era, Jackson’s military leadership helped build America as a strong continental power, pushing away potential rivals for national territory. Indeed, Jackson’s military success in Florida persuaded Spain to cede that peninsula to the U.S. in 1819.

In other words, while the moral issues involved in Jackson’s policy can be seen clearly now, at the time they were clear in a different way.

In 1823, admiring Tennesseans once again elected Jackson to the U.S. Senate. Then, in 1824, running for the presidency of the nation; he won the popular vote by more than 10 points—although he lost in the electoral college and thus was denied the White House.

Four years later, Jackson ran for president again, leading a newly configured party, now known as the Democratic Party. He won the popular vote again, this time by almost 13 points, defeating incumbent John Quincy Adams. Indeed, the 1828 election has been called the “revolt of the rustics,” as Jackson enabled and inspired a broad increase in voting, thus creating a populist-minded “Jacksonian Coalition,” including both Northerners and Southerners. That’s a coalition that wins elections to this day.

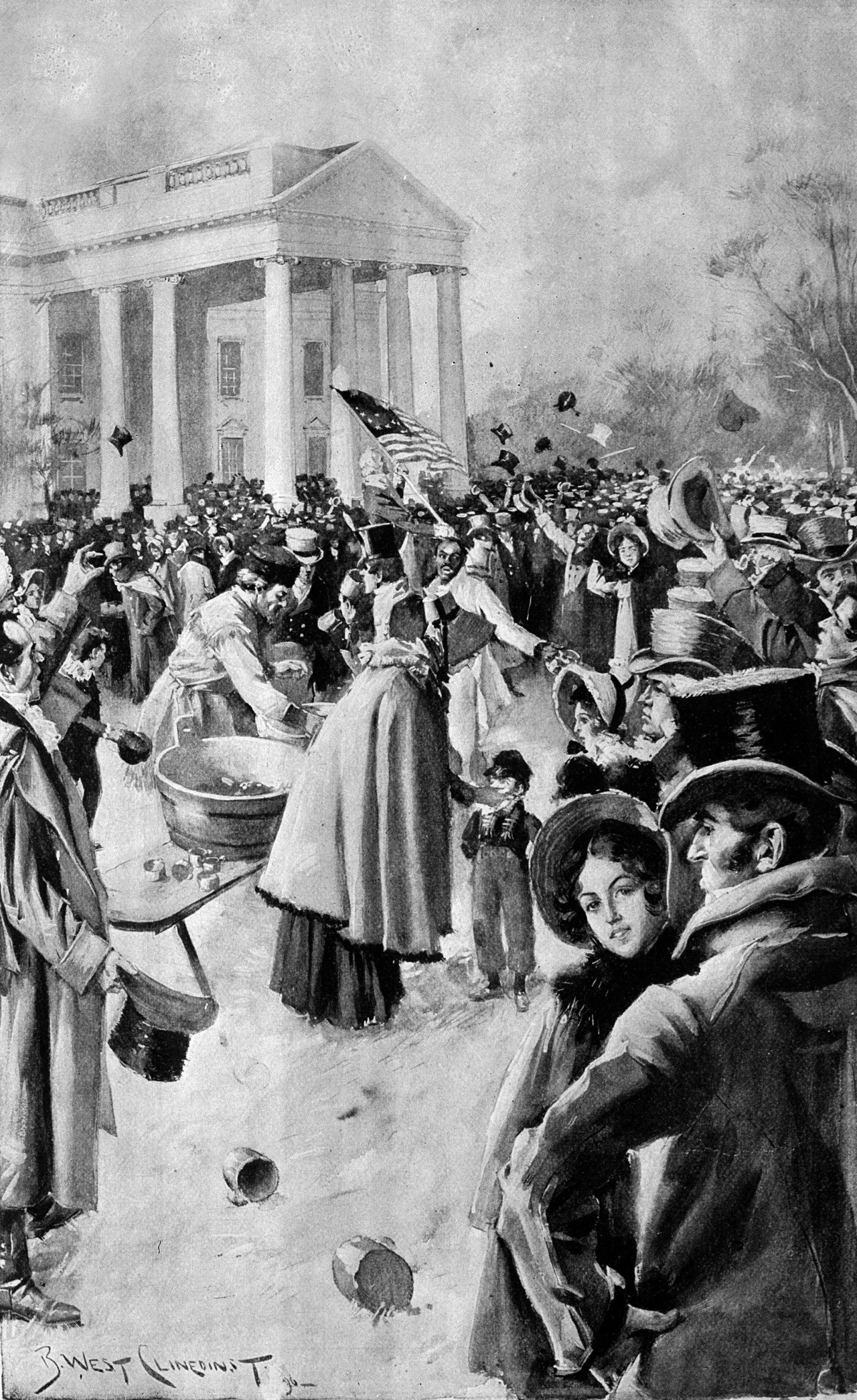

This artist’s rendition shows the crush of people after President Andrew Jackson’s inaugural ceremony, held on the East Portico of the Capitol building for the first time, in Washington, D.C., on March 4, 1829. More than 20,000 well-wishers came to the White House to meet President Jackson following the inaugural. (AP Photo)

Indeed, upon his inauguration in March 1829, the new president threw open the doors of the White House, so those same rustics could join him in person for the festivities. Four years later, he was re-elected by an even bigger margin–almost 17-points.

We might add that during his eight years in the White House, Jackson was true to his word–he governed as a populist. One of the raging controversies of his time was the existence of the Bank of the United States (BUS), a sort of forerunner to the U.S. Federal Reserve. Jackson was intensely suspicious of the BUS, seeing at as unfair concentration of economic power in Philadelphia, then the nation’s largest city. So President Jackson allowed the BUS’ charter to lapse, thus dissolving it, to the delight of his supporters. Moreover, Jackson actually succeeded in paying down the national debt to zero. He is the only president to have done so.

We can look at the historical record and see for ourselves that few presidents were as popular in their day as Jackson was in his. There’s a reason why–beyond that mighty, albeit endangered, statue in downtown Washington, D.C.–there are so many places named “Jackson” and why his rugged image graces the $20 bill.

And yet Jackson was a lot more than popular. He was always–and for this he deserves to be remembered–a stalwart patriot.

Jackson was a Southerner and, yes, a slaveholder. And yet at the same time, he never deviated in his loyalty to the nation he served for six decades. He was first and always a strong supporter of the United States of America. In a celebrated 1830 showdown with fellow Southerners, Jackson declared: “Our federal union: It must be preserved!”

Jackson died in 1845, long before the onset of the Civil War, and yet there can be little doubt that that he would have opposed Secession.

And that’s why Jackson’s ringing words—“Our federal union: It must be preserved!”—are inscribed on the base of the statue that sits in Lafayette Square.

So this is the American hero whose memory the howling mob wants to destroy. It’s a safe bet that most of the would-be statue-topplers know little or nothing about Jackson, beyond the fact that some professor told them that he was a racist, genocidalist, and white supremacist.

Moreover, many of the smashers simply want to do harm; after all, as we are told in the Book of Proverbs, the wicked “Cannot rest until they do evil; they are robbed of sleep till they make someone stumble.”

These are the forces of anarchy that we’re up against: the people following some lunatic vision of political correctness, aided and abetted by those who simply want to wreck things.

And we should realize: Even though these vandals were thwarted on June 22, they will no doubt be lying in wait, aiming to strike if the police aren’t on guard.

Thus, the guardians of our order must always know that we, the public, have their back.

In his time, Andrew Jackson had to confront threats to the nation—always defending it with courage and resolve.

Now it’s our turn to show courage and resolve defending him.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.