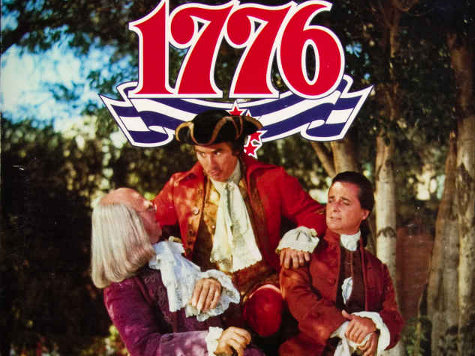

In my home, Independence Day doesn’t go by without our annual viewing of the landmark 1969 Broadway musical “1776.”

Written by Sherman Edwards and Peter Stone, it ran for 1,217 performances. It’s hard to believe that forty-three years ago, it was still popular to write an unabashedly patriotic musical that openly celebrated American exceptionalism and painted the founding fathers not just as humans but as the intellectual and moral giants that they were. Because the 1972 film version is tantamount to a filmed version of the play rather than a Hollywood re-interpretation, its original intent and form is easily accessible to today’s audience. It deserves a good look and therefore, on this July 4th, let’s take some time exploring and enjoying this American musical about America:

“1776” uses the character of John Adams as the protagonist, telling the story of his legendary fight to convince the continental congress to adopt a resolution calling for independence from King George. The show follows the journey of Adams’ victories convincing congress to form a committee to draft the Declaration of Independence, the ensuing debate over the contents of the declaration, the conflict between the Northern states and the Southern states over slavery, and, finally, the climactic scene depicting the signing of the declaration.

The brilliance of the drama in this show is not “will they do it?” since everyone in the audience knows they will. The drama lies in “how are they gonna pull this off?” The show uses a simple but very theatrical and dramatic device by showing a giant day calendar on the wall above John Hancock’s desk. Each new scene shows the calendar page ripped away revealing what day we are witnessing. Everyone with at least a first grade education knows we are all counting down to July 4th, and the tension genuinely builds as we see the day coming closer and yet it doesn’t seem like Adams and his coalition will get all of the states to favor a declaration in time.

“1776” is unique in many ways. Most striking is the fact that the stage is populated by many, many men, and there are only two women in the show: Abigail Adams and Martha Jefferson. And Abigail only appears through her letters with John; she does not actually interact with the rest of the cast. Martha only appears for one scene, a somewhat apocryphal moment when Franklin and Adams send for her to provide Jefferson a much needed conjugal visit so he can re-focus on the writing of the declaration.

So, other than that, it’s a 2 & 1/2 hour-long musical with a bunch of wig-wearing guys sitting around debating in 18th century aristocratic costumes. No chorus, no dancers, no special effects, no leggy dancers… not really the recipe for musical theatre success.

Because the film was such a faithful replica of the stage production, using most of the same principal actors, clips from the film should provide you with a great taste of what it was like to witness this show live at the 46th Street Theatre (now the Richard Rodgers) 43 years ago. Here is the great opening number, “Sit Down John!”:

How great is that? “One useless man is called a disgrace, two are called a law firm, and three or more become a congress!” That’s the great William Daniels playing John Adams, a role he will always be associated with. And what brilliant writing as the congress is in a great debate over the pros and cons of opening a window? They all agree it is too hot, half want the window open, the other half don’t want to let in any flies, Thomas Jefferson forms a coalition trying to strike a compromise… it seems the only thing the entire congress can agree on is their hatred of Adams.

In one opening number, Sherman Edwards defines the character of Adams and his single-minded focus on pushing the issue of independence, plus he illustrates the ineffectiveness of congress and their antagonism to Adams–all put to song. I’ve said it before: great musicals are often defined by their opening number.

Another thing to note as these clips keep coming: one of the most thrilling things to hear on stage is a full male ensemble singing robust songs in multiple parts. There is something about hearing great male singers in full voice with close layers of harmony. “Guys and Dolls,” “Les Miserables,” “The Music Man,” and “1776” all feature songs like this, and it never fails to please the audience.

One of the great surprises of “1776” is how much humor there is in it. At first glance, it’s pretty dry stuff, but Edwards and Stone take great liberties with facts about the characters of these men, then expand upon those traits to make the comedic elements of their personalities as broad as possible.

Here’s an example. It’s no secret that the Lee family of Virginia was historically prominent and influential. Dating their origin to the Jamestown colony in 1639, they became established in the colonies through tobacco farming and politics. They were the Kennedys of their time–rich and political and not a little pompous.

History tells us that one of the strategies Benjamin Franklin and John Adams used to move the Declaration of Independence along was to get Richard Henry Lee to make the motion in congress. He was so respected and carried so much weight that he would be accepted as the sponsor of the resolution (where as Adams was hated by all). It was up to Lee to ride to Virginia to get the approval of the House of Burgesses to make the motion. Here’s how “1776” portrays the man and the moment:

I’m glad the scene is included before the song as well. You can see how brilliantly Stone uses actual quotes from giant men like Franklin and incorporates them seamlessly into the dialogue. Also, Stone clearly has a reverence and love for these men and what they did. Make no mistake, this is “American Triumphalism, the musical,” and there are no apologies made. You see this show and you learn one thing: America is great. Period.

Okay, gotta show a little more of the humor and then we’ll move on to the meatier stuff. Here’s a brilliant song depicting the debate within the committee over who should write the Declaration of Independence. Again, pay attention to the clever lyrics.

Franklin:

Mr. Adams, but, Mr. Adams

The things I write are only light extemporania

I won’t put politics on paper; it’s a mania

So I refuse to use the pen in Pennsylvania

Sherman:

Mr. Adams, but, Mr. Adams

I cannot write with any style or proper etiquette

I don’t know a participle from a predicate

I am just a simple cobbler from Connecticut

By the way, yes, that’s Ken (The White Shadow) Howard as Thomas Jefferson.

So, the aforementioned conjugal visit between Jefferson and Martha occurs, and Franklin and Adams wait for him to emerge from his chamber. What follows is a wonderful scene between the two of them speculating about how history will (or will not) view them, and then comes Martha to sing the praises of Tom. On Broadway, it was a young Betty Buckley wowing Broadway audiences for the first time. Here on film, it’s the sumptuous and aptly named Blythe Danner. Oh, how I miss seeing her on stage, and how superior she is on film to her daughter.

And there you have it. All Jefferson needed was one night with Martha, and the next morning he cranks out the Declaration of Independence! Who knew? If I had one night with a young Blythe Danner, who knows what great writing I’d be capable of?

So, now things get a little tricky. You see, the block of voters who oppose the declaration and wish to keep their allegiance with the King are labeled in the show as “Conservatives.” This was a real sticking point in 1969 when the show came out and in 1972 with the film. In fact, the Nixon Administration complained at the characterization of those against the creation of our country as being the forefathers of the modern conservative movement.

Frankly, knowing that the vast majority of millionaires in the Senate are Democrats, and knowing that the ideals Adams, Jefferson, Franklin and Washington represented fit perfectly with the values of the modern conservative movement, I don’t see the problem. But if you think in shallow terms and watch this scene thinking that these guys represent the “Republicans,” then yeah, I think you can see the problem:

I have no idea about Stone and Edwards’ politics, but I do know that as a conservative thinker, I can watch this show and love all that is great about America. I feel pride with my spiritual connection to the forefathers and celebrate their courage and brilliance. I am not forced to defend my modern-day political perspective and I can objectively feel a kinship with these men and respect for the revolution they spawned. If a modern-day conservative sees themselves in that number, it’s more a problem with their own perspective and self-analysis, not a problem with the writing.

So the original draft of Jefferson’s declaration is read and debated, almost line by line. And slowly, Adams wins his votes and Jefferson loses large chunks of his original draft… until the issue of slavery is approached. As we know, Jefferson’s original draft had language decrying the ownership of slaves (modern revisionists overlook this and ignorantly paint Jefferson as nothing more than a racist slave owner). The Southern states refuse to sign on until the language is removed and Adams and Jefferson dig in. Notice the brilliant staging in the way Franklin is positioned, observing:

Franklin convinces Adams to let it go; the issue of independence was too important and they agree to let future generations work out the problem of slavery (four score and seven years in the future, to be exact). The final scene depicts, of course, the signing. When staged properly, it brings chills and cheers:

The good humor and joshing regarding the consequences of their treasonous act is immediately shifted to the weight and reality of the situation upon the reading of the dispatch from General Washington. And with bells tolling and the orchestra swelling, our country is born.

Here’s a bit of trivia about this play: in the first act, scene three, during the initial debate over independence, there is a twenty-two minute stretch of unending dialogue without any music to interrupt it. This is the record for the longest duration of time in a musical without a single note of music. In this day of rock opera and endless, banal recitative, it’s so refreshing to see a musical not be afraid to talk to the audience rather than sing at them.

One more bit of trivia: years later, William Daniels starred in the great and under-appreciated NBC drama “St. Elsewhere.” In the final season, they had a storyline that took his character to Philadelphia. In one scene, he is walking around the grounds of Independence Hall and says, “I don’t know what it is about this place but it makes me want to get up and sing.” Few got the inside joke (good Lord, I really am a geek, aren’t I?).

For our finale, I want to take you back to the opening number. This time, the video is of the Broadway cast of the recent revival as seen on the Tony Awards. Pay close attention to those magnificent male harmonies as they are even more evident in this version versus the film version seen above.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.