WARSAW, Poland (AP) — In the decades since the end of World War II, reminding Germany of its Nazi past has become a temptation whenever tensions arise over current events in Europe.

So recent assertions by politicians in Warsaw that Germany owes Poland reparations for the mass atrocities and destruction the brutal Nazi occupation of the country are being met with skepticism from some, even though many Poles support the calls.

The Polish government has not named a sum, but lawmakers and sympathetic media outlets estimate Germany owes Poland anywhere from hundreds of billions to several trillion dollars for the six years the Nazis occupied Poland, set up death camps and killed nearly a fifth of the population.

“Poland is only asking for justice … The injury has not been repaired in any way at all. Just the opposite,” Prime Minister Beata Szydlo said last week. This week, however, she said the government hasn’t yet decided whether to make an official demand.

Germany says the matter of financial compensation was settled long ago, and international legal scholars agree Poland has no legal claim to compensation at this point. What’s more, the demand has emerged amid rising tensions between Poland and Western European powers.

The timing has caused some political observers in Poland to accuse Szydlo and her ruling Law and Justice party of fomenting anti-German sentiment to distract voters from other problems, mainly criticism from the European Union and prominent members Germany and France over the party’s erosions of rule of law.

“For Law and Justice, it’s good to show in this moment that the Germans owe us something,” said Agnieszka Lada, an expert on Polish-German affairs with the Institute of Public Affairs in Warsaw. “The point isn’t money. The point is that Germany should not dare lecture Poland.”

File-In this Oct. 1, 1945 file photo, a solitary cyclist contemplates a panorama of total destruction in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, months after World War II. (AP Photo,file)

Ryszard Czarnecki, a Law and Justice member and vice-president of the European Parliament, told The Associated Press that the ruling party, more popular now than when it won the 2015 general election, has no need for diversionary tactics.

“The current Polish government has a feeling that this is the will of Polish citizens and that we are owed this historically, legally and morally,” Czarnecki said.

The calls for reparations started in July when Law and Justice leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski said that “Germany for many years refused to take responsibility for World War II” and the Polish government was preparing “a historical counteroffensive,” renewing calls that have emerged in the past, also in times of tensions with Germany.

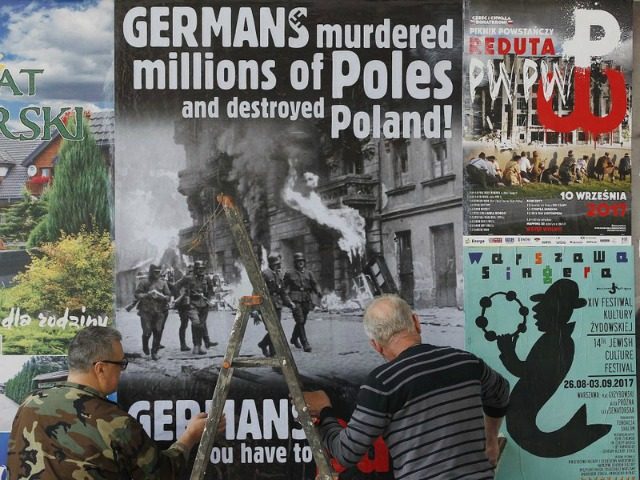

Within days, party lawmakers, pro-government media and other groups joined the campaign. One group plastered pro-reparations posters on the sides of some buildings in Warsaw. Surveys show a majority of Poles think Germany still owes them.

“They got rich. They robbed Poland completely of gold, money, everything,” said Bogumila Tkacz, 75, who was born during the war. “Where is all of that? We had so many cultural goods, paintings, everything. Everything is gone, no one returned anything.”

Berlin says the issue of reparations was settled in 1953, when Poland’s communist government renounced its right to war-related compensation, a position Warsaw reconfirmed over the years. Individual Poles — including Polish slave laborers and victims of scientific experiments and Polish-Jewish Holocaust survivors — have received compensation from Germany. In the postwar redrawing of borders Poland was given substantial territory previously in eastern Germany, though that wasn’t strictly considered reparations because Poland had to renounce territory in the east to the Soviet Union.

Some government critics think it is no coincidence that restitution calls have resurfaced as Poland faces mounting criticism from the EU over issues such as new laws giving the ruling party greater control over the judicial system, and widespread logging in the primeval Bialowieza Forest.

Grzegorz Schetyna, leader of the main opposition party, Civic Platform, says he sees Kaczynski’s reparations calls as a “sham” issue aimed at creating anti-European feelings as part of “an attack on the European Union.”

Those sentiments are mainly aimed at Germany, the largest and most dominant EU country. Relations between Berlin and Warsaw have been steadily worsening since Law and Justice’s election.

The Polish government vehemently opposes German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s refugee policies and has refused to accept any migrants in an EU resettlement plan, prompting the European Commission to launch a lawsuit against Poland.

Law and Justice is planning a law this fall that would nationalize dozens of Polish newspapers, magazines and news websites owned by German publishing companies, saying it objects to massive foreign control in the nation’s media sector.

Kamila Gasiuk-Pihowicz, a prominent member of Poland’s liberal Modern party, said the antagonistic stance would only sour ties and discourage new German investments in the country.

“These actions hurt Poland,” she told the AP.

This isn’t the first time — and probably won’t be the last — that the atrocities committed by the Nazis have come up in contemporary European politics.

Germany faced demands from Greece two years ago for multibillion-euro reparations amid tensions over pushing austerity on the Greeks during their financial crisis. Greece, also subjected to a brutal wartime occupation, even threatened to seize German-owned property, but never followed through.

In 2004, as some Germans sought to reclaim property on land that was given to Poland after WWII, then-Warsaw Mayor Lech Kaczynski, who would go on to become president, calculated that Germany owed $45 billion dollars for the destruction of Warsaw alone.

More recently, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused Merkel of using “Nazi” methods amid tensions between Berlin and Ankara.

These are mostly exercises in political rhetoric 78 years after the start of the war, an anniversary Poland will observe on Friday.

Michael Bazyler, an expert in international law and restitution at Chapman University School of Law in California, said the Western allies and the Soviet Union chose not to force a defeated Germany to pay massive reparations, having seen how the punitive conditions of the Treaty of Versailles after World War I contributed to the rise of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi party.

“Does Germany owe compensation? Yes. But will (Poland) be able to get it? Absolutely not,” Bazyler said.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.