CARACAS, Venezuela – Of all the woes bought upon us by Venezuela’s “Socialism of the XXI Century,” this is the one where my life took the heaviest blow, and the one where the government’s hypocrisy and indolence shine the most.

Venezuela used to boast a dual public and private health system, neither of which were close to perfect, but you always had the choice.

My parents were doctors that worked in both sectors in tandem. My grandmother was a humble nurse that retired before I was born. My mother, an anesthesiologist (with five extra medical specialties) was the head of the reference Pain Management and Palliative Care Unit in the Miguel Perez Carreño Hospital in Caracas, Venezuela, for sixteen years. So I was very familiar with the limitations and hardships of the public health system before socialism. I’ve lived in three different cities in Venezuela and I often walked through the corridors of hospitals as a child.

Still, despite all the shortcomings that the public sector has had, it always functioned as best as possible in my youth. That is not the case anymore. Our health crisis has claimed the lives of so many. I will always have the utmost respect for our doctors and health professionals because, despite all of the hardships they face – even having to perform surgery without power – they still work tirelessly and save lives.

The continued collapse of the country has affected the private sector as well. You have to bring your own supplies to surgeries, from gauze to bandages or antiseptic products — that’s how bad it’s gotten.

In 2015, a word changed our lives forever: Leiomyosarcoma.

My mother was diagnosed with this rare form of cancer in her liver after months of misdiagnosis. What followed was a long two-and-a-half-year fight against this atypical cancer with the country’s collapse stacking all odds against her. She fought as hard as she could but, without access to proper chemotherapy and treatment, she passed away on March 31st, 2018.

I hadn’t had a good night’s sleep since her initial diagnosis. Ever since she passed away I sleep even less.

My mother never received proper treatment from day one due to the lack of supplies that weren’t just related to her chemotherapy, but the meds involved in the post-treatment that followed each round of chemo as well. Foreign supporters of dictator Nicolás Maduro love to blame “U.S. sanctions” for our woes, but this was in 2015 – Donald Trump wasn’t even the Republican candidate yet, and the Obama administration took a more laid back attitude towards Venezuela than its successor.

More often than once we had to go to the Venezuelan Social Security Institute’s high-cost pharmacy to find her chemotherapy meds when the private suppliers had none. The mistreatment government employees offer to patients there is abhorrent (many of which are elderly). Long lines and despair were all I could see in each of our visits to that place.

An image of Hugo Chavez is pictured in a reception office -now used to place old stuff- at the Dr. Miguel Perez Carreno Hospital, in the west of Caracas, Venezuela on December 31, 2018. (Photo by YURI CORTEZ / AFP)

By 2016, Human Rights Watch revealed that 76 percent of public hospitals lack basic medicines, including some that are listed on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) List of Essential Medicines.

Even finding antacids for her was an odyssey on its own; the government added them to the list of banned import items simply because they can be used to neutralize the effects of tear gas in protests. As a result of antacid shortages my mother had to drink water mixed with baking soda.

In 2017, her tumor had stabilized and would’ve gone into remission had she received proper chemo, but she was only receiving a partial treatment due to the unavailability of the other half; thus, another treatment was tried, much harder to find as well, but it wasn’t effective because it was too late.

Her last option at that point was Votrient (Pazopanib), a last-resort choice that had shown very positive results for others. The problem was that this medicine wasn’t found anywhere in the country. The last known box (at the time) owned by a private supplier was sold out to another person in another town.

We spent the rest of 2017 desperately trying to obtain it to no avail. Since the treatment that could’ve saved her life was not available, her friends were able to procure another type of chemo that wasn’t the ideal one, but it was better than nothing.

The side effects were numerous, to the point that it started to affect her mobility. In spite of that, we tried our best to have a normal New Year’s celebration all things considered — little did I know was that it would be our last together. Her condition worsened so fast through the first months of 2018, her 60th birthday was a very bittersweet one.

I had to take her to Perez Carreño’s emergency room on March 9 when she started to retain fluids and wasn’t able to breathe properly. It wasn’t the best of days.

When we arrived, I saw a crowd of people in an exterior waiting area next to the gates of the emergency room since companions are usually no longer allowed inside. The hospital’s gates had long since been militarized. My mother was taken inside in a derelict and worn-out wheelchair as I found a place to park her vehicle.

As we waited inside for her to be admitted in, one of the nurses demanded the wheelchair back because there’s a shortage of them – you heard it right, a hospital with a wheelchair shortage. I refused, my mother said that the other seat was very uncomfortable for her breathing.

I even pleaded with the guy saying that she had given sixteen years of her career to the hospital so the least they could do was let her use it. We were close enough to fighting that we were split. A doctor finally attended her and said she needed blood tests that they couldn’t do. I didn’t want to leave her alone, but she assured me that she’d take care of herself. I took the samples and drove in search of an open lab that could do them (yes, a hospital that can no longer do blood tests).

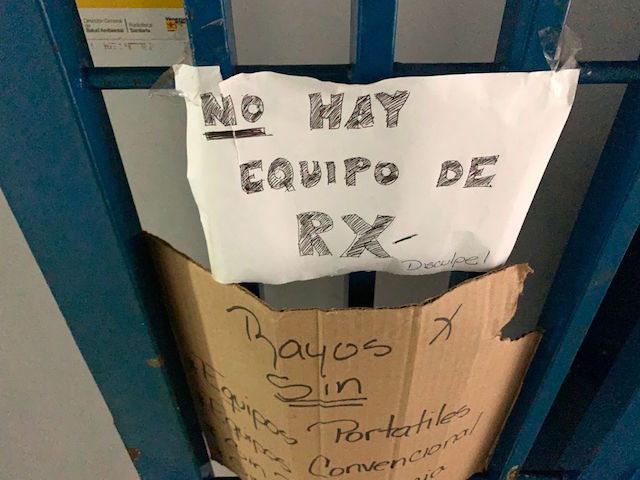

A sign reads “No X-Ray Machine” in the Jose Manuel de los Rios Hospital, the main public pediatric hospital in Venezuela, in Caracas, on May 24, 2019. (Photo by Marvin RECINOS / AFP)

Picture of damaged medical equipment taken in a deteriorated area of the Jose Manuel de los Rios Hospital, the main public pediatric hospital in Venezuela, in Caracas, on May 24, 2019. (Photo by Marvin RECINOS / AFP)

A patient looks out from a window at Miguel Perez Carreno hospital, in Caracas, during the worst power outage in Venezuela’s history, on March 8, 2019. (MATIAS DELACROIX/AFP via Getty Images)

Three weeks later, she lost the fight against cancer. A friend of my mother’s had to smuggle morphine into the hospital so that she could spend her last hours without pain.

Nothing could’ve ever prepared me to see my mother’s body, covered in the same bedsheets I bought for her (you must supply your own bedsheets and the hospital doesn’t have those fancy bags), in a row of corpses, devoid of refrigeration.

Hospitals do not have proper refrigeration for the dead.

The person attending the morgue used to operate one of the hospital’s elevators. She knew my mom in life and expedited the paperwork because my mom helped with her sister’s palliative care, providing her with painkiller cocktails and whatnot. Sparing her body from decomposition was a last “thank you” on her behalf.

My mother never deserved to go through any of this. It wasn’t fair for her. But, then again, that’s how life goes in Socialist Venezuela. It’s been a year and I still feel devastated by all the things she had to go through. Proper sleep still eludes me. My blood boils every time I see the regime’s politburo brazenly state that there’s no health or humanitarian crisis here — we all know it’s a lie.

My mother’s last email was addressed to a contact of hers at Pfizer that went unanswered, in which she asked for info regarding those pills that she needed to live.

Just like my mother, there are so many cases of people dying due to a lack of medicine or treatment, many of which could’ve been prevented. Transplant recipients have begun losing their organs because, without treatment, their bodies reject the transplant.

My mother wrote, “Cancer is a word, not a sentence” in her bible, but the government’s stubbornness and refusal to admit its mistakes is definitely turning any medical condition into a death sentence.

I recently talked to the nurse that worked with my mother all those years. She tells me that the pain and palliative care postgraduate that my mother used to run has been shutdown. The unit that my mother built from the ground up is still working, albeit at a very reduced capacity, with barely any supplies and with only two doctors left – one of which is poised to leave the country soon. Perez Carreño’s Cardiology, Level III Trauma, and High-Risk OBGYN departments have been shut down.

My father, who lives in another town, tells me that the Department of Pathology that he runs has been placed in a technical shutdown. They do not have the materials and reactives required to process biopsies and to perform cytology tests. The only answer he received from the hospital’s directive is that he should contact other hospitals and barter what he has for what he needs.

His long-overdue retirement has been placed on hold until a replacement is found. My mother went through a similar situation, forcing her to play the “cancer card” to get a special retirement that amounted to less than what a regular one entailed. With a large bulk of Venezuela’s doctors fleeing the country due to the dire situation of everything, how dangerous things have become for doctors, and the absurdly low wages, my father is not expecting his retirement to happen anytime soon.

Another related anecdote that I will never forget took place in 2017, amidst the heavy protests of the time. I was accompanying my mother in “BADAN,” a private pharmacy chain that specializes in antineoplastic treatments.

Of course, there was a large line, so large that they had decided to add an expedited line for those that simply wanted to ask about the availability of meds; a resounding “no” or “we ran out of it” was almost always the answer.

There was a young brown-skinned woman to my left, definitely younger than me. She was very distraught. Her anguished face is something I won’t ever forget.

When it was her turn to ask, she pulled a piece of paper from her backpack and began to recite a list of medicine that she needed for her seizures. Not a single one of them was available. She broke down in tears, saying that she had been without treatment for weeks and this place was her last hope.

I pray to God that she’s safe and sound.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

This article is the fourth in a series on life in Venezuela. Begin the series here. Continue the series here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.