There is irony in the convergence of two story lines this month.

In the aftermath of a contentious U.S. presidential campaign, the first involved concerns over the rise of fake news stories online. As one critic notes, they “proliferate on social media… often shared more than real news is.”

That critic suggests, “To remove the appeal of fake news, people need to value debate and discussion with those who hold opposing views.” Sadly, as the presidential campaign demonstrated, the public leaves its education to the Internet and not debate.

But such fake news stories are not an evolutionary evil of the Internet. The rise of fake news stories to manipulate public sentiment existed long before the Internet became a gleam in Al Gore’s eye. Late 19thcentury America bore witness to “yellow journalism”—the practice of sensationalizing stories to stir up public sentiment and newspaper sales.

The second storyline this month involved the death of Cuba’s nonagenarian former president and dictator, Fidel Castro, 90, who unabashedly took credit for having long ago fed the New York Times (NYT) fake news.

In 1952, a coup by General Fulgencio Batista overthrew the democratically elected Cuban government. The following year, Castro and a small group of followers formed “the Movement.” The group undertook sporadic guerrilla operations against Batista.

By 1957, the Cuban Revolution had stalled. The NYT began publishing a series of pro-Castro articles portraying him as a freedom fighter seeking to restore democracy to the island nation.

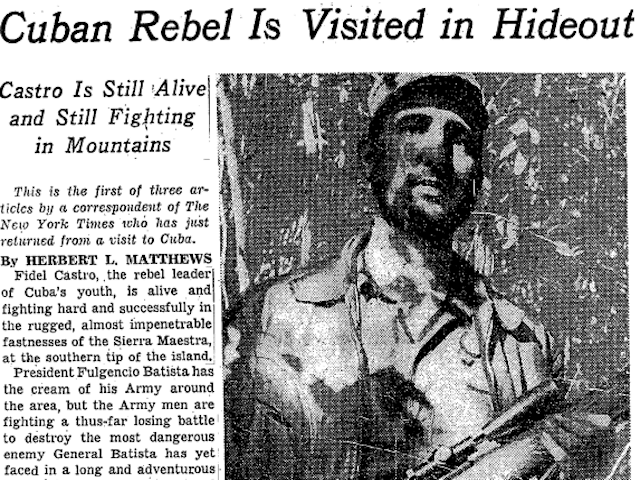

When questions surfaced in early 1957 regarding whether Castro was even alive, Fidel agreed to a NYT interview, at his mountain hideout, with reporter Herbert Matthews. Matthews’ article gleefully reported Castro was still alive and the Cuban government was fighting a “losing battle” against him. Matthews described an abundance of activity and troop movements in and out of Castro’s hideout.

The articles elevated Castro’s profile, giving him credibility both at home and abroad and helping propel his rise to power. In January 1959, the Batista government fell—and Fidel, the avowed democratic leader, established a revolutionary socialist state. In 1965, the Movement revealed its true colors, becoming the Communist Party.

During a triumphant 1959 visit to New York City, Castro claimed his “greatest ploy” was fooling Matthews. Castro said he only had twenty men left at the time but convinced Matthews he had control of a huge army. Matthews’ observations supported this as he wrote, “From the look of things, General Batista cannot possibly hope to suppress the Castro revolt.”

Castro accomplished this ploy by marching “the same group past Matthews several times and also stag(ing) the arrival of ‘messengers’ reporting the movement of other (nonexistent) units.”

Former NYT correspondent Anthony DePalma wrote a biography about Matthews. DePalma suggests while Matthews was “guilty of sloppy reporting,” he believes Castro’s fake story that he allegedly fed Matthews may, in itself, be fake, as he questions whether Matthews was really “duped.”

Nonetheless, it is clear one or the other fielded a fake news story.

But what is being written now about the dictator by Western journalists in the wake of Fidel’s death leaves an educated reader wondering whether the fake story mill is still at work or whether it is just sloppy reporting again.

Perhaps taken in by Matthews’ glorification of Castro almost sixty years earlier, the NYT continues the propagandist line as to Fidel’s accomplishments.

Despite the NYT’s post-U.S. presidential election demands for more responsibility monitoring fake news, in writing about Castro, its reporting staff failed to get the word. The newspaper pays tribute to the brutal dictator as “the fiery apostle of revolution” who “bedeviled 11 American presidents…” Only buried deep therein is any reference made Castro wielded power “like a tyrant.”

In a final Castro salute, the NYT suggests: “His legacy in Cuba and elsewhere has been a mixed record of social progress and abject poverty, of racial equality and political persecution, of medical advances and a degree of misery comparable to the conditions that existed in Cuba when he entered Havana as a victorious guerrilla commander in 1959.”

This salute stands in stark contrast to a book written by the “Cuban Solzhenitsyn,” as Armando Valladares is known, who spent 22 years in the country’s dungeons. Titled Against All Hope: A Memoir of Life in Castro’s Gulag, his book is credited with revealing Cuba’s communist tyranny to the same extent Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago revealed Soviet despotism. Dictators’ names may differ but the suffering of the ruled under communism did not.

Sadly, the NYT was not alone in its tribute to the tyrant. Other reporters have spoken glowingly of Castro, comparing him to “George Washington.” MSNBC’s Chris Matthews (surprisingly unrelated to the NYT reporter) asserted Castro was “a romantic figure when he came into power…(who) was almost like a folk hero to most of us.”

Castro was known to be a verbose orator. A speech given at the U.N. General Assembly lasted four-and-a-half hours; another, to the Communist Party Congress, logged seven. Undoubtedly, his gift of gab has Castro still droning on at this very moment, trying to convince Saint Peter to allow him entry. If so, Castro will encounter at least one listener unwilling to buy into his fake story.

Lt. Colonel James G. Zumwalt, USMC (Ret.), is a retired Marine infantry officer who served in the Vietnam war, the U.S. invasion of Panama and the first Gulf war. He is the author of “Bare Feet, Iron Will–Stories from the Other Side of Vietnam’s Battlefields,” “Living the Juche Lie: North Korea’s Kim Dynasty” and “Doomsday: Iran–The Clock is Ticking.” He frequently writes on foreign policy and defense issues.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.