It seems clear enough that the Trump administration is not pleased with the conduct of the U.N. Human Rights Council. According to the ever-popular roster of unnamed current and former U.S. officials, the administration is considering a complete withdrawal from the HRC, reports Politico.

Politico worries that “discussion of abandoning the council is likely to alarm international activists already worried that the United States will take a lower profile on global human rights issues under President Donald Trump.”

That is speculation and so is virtually everything else in the article, which is based entirely on the word of a former State Department official, name and previous rank unknown, who claims to have been “briefed on the discussions.” One would think the Trump administration might have grown cautious about briefing former officials on anything of importance, given the issue of possible leaks.

It is not implausible that the Trump team would discuss withdrawing from the HRC or perhaps seek to rattle a few cages at Turtle Bay by letting it be known they are contemplating withdrawal. This president and his team have a penchant for winning at least rhetorical concessions by questioning the unquestionable as the first step in negotiations. It is too early to say if those rhetorical concessions will become concrete advantages.

The tenor of the discussions described by Politico’s source also sounds believable:

A former State Department official briefed on the discussions said while the council’s targeting of Israel is likely part of the debate, there also are questions about its roster of members and doubts about its usefulness overall.

Countries known for human rights abuses, such as China and Saudi Arabia, have managed to snag seats on the 47-member council.

“There’s been a series of requests coming from the secretary of state’s office that suggests that he is questioning the value of the U.S. belonging to the Human Rights Council,” the former official said.

In a recent meeting with mid-level State Department officials, Tillerson expressed skepticism about the council, which has a number of powers, including the ability to establish panels that probe alleged human rights abuses.

As Politico notes, the current iteration of the U.N.’s human rights organ only dates back to 2006 when the HRC replaced the even more risible Human Rights Commission, “which had faced severe criticism because countries with poor rights records became members and prevented it from carrying out its mission to the fullest.”

Ironically, speaking up for Israel was presented by the Obama administration as one of the reasons for joining the HRC, but their final act on the international stage was a highly conspicuous refusal to do so.

In fact, as Human Rights Voices president Anne Bayefsky notes in a National Review piece, the ten-item permanent agenda for the Human Rights Council includes one item “devoted to human rights violations by Israel,” plus one “generic agenda item” for the other 192 U.N. member states combined.

“A 2016 Council resolution calls for the creation of a blacklist of all companies that are connected with or do business with so-called Israeli settlements ‘directly or indirectly.’ Not surprisingly, the Council has no comparable boycott scheme for the world’s most heinous regimes,” Bayefsky writes. “The boycott plot is a full-scale assault intended to strangle Israel economically, in order to compensate for successive failed attempts since 1948 by Israel’s enemies to annihilate the Jewish state on the actual battlefield. American companies that do business with Israel are clearly in the Council’s crosshairs.”

The Times of Israel concedes the Human Rights Council has a murky 11-year history but gives it credit for some “successes,” by which it seems to mean humanitarian horrors such as North Korea and South Sudan “remain on the agenda.” Actual improvements in real-world human rights attributable to the HRC are difficult to identify.

Defenders of continued U.S. membership are largely driven by the fear that American withdrawal would send a terrible message to the monsters of the world.

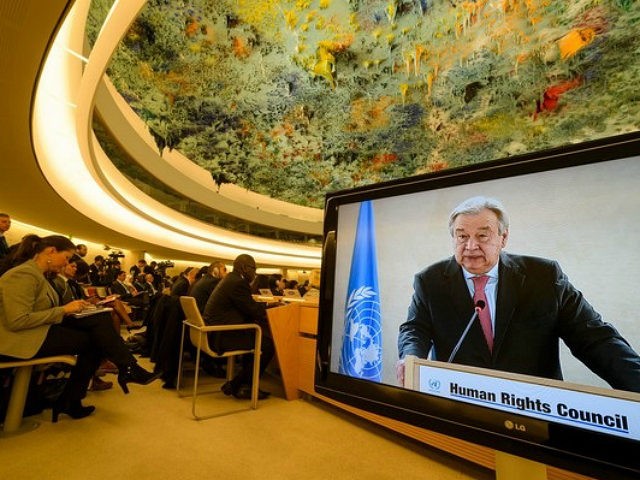

For instance, U.N. Secretary General Antonio Guterres declared, “Disregard for human rights is a disease, and it is a disease that is spreading. The Human Rights Council must be part of the cure.” It is tough sledding when even the most ardent defender of the HRC admits the social disease it was created to fight is still spreading.

“Clearly ‘America First’ does not suggest an approach that (prioritizes) multilateral engagement,” the Times of Israel quotes John Fisher of Human Rights Watch declaring. Why would an American, re-dedicated to pursuing its own interests, not be an effective champion for human rights, able to engage with nations across the globe in that noble pursuit? The sternest critics of the United Nations say its bureaucracy reduces our effectiveness in that role, but accepting that argument would require U.N. defenders to admit America is exceptional on freedom and human rights. They also worry that ineffectual bureaucracies with lengthy “agendas” but little real-world influence effectively provide cover for the worst abusers by creating the illusion of progress.

At the moment, the United States is still part of the Human Rights Council; State Department spokesman Mark Toner made it clear the U.S. delegation “will be fully involved in the work of the HRC session which starts Monday.”

Far too many of the officials and activists who insist upon continued American membership seem to regard President Trump’s executive order on immigration as a more pressing concern than the mountains of corpses or dungeons full of dissidents piled up by the dictators and fanatics of the world. Some of them seem to think the United States, withdrawing from the Human Rights Council or even criticizing it harshly, is a more serious offense than dropping cluster bombs on civilians.

As things stand, despite all the talk of vital probes and investigations launched by the United Nations, the penalty for temporarily suspending immigration from six countries plus one tyrannical terrorism-sponsoring theocracy is roughly the same as the penalty for slaughtering civilians or maintaining torture chambers. The Trump administration might wish to learn if champions of the Human Rights Council can offer some positive inducements for remaining engaged, rather than threatening their severe disapproval in the event of withdrawal.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.