The collapse in oil prices over the last seven months looks to destabilize the world stage by redirecting over $1.8 trillion in spending if current prices hold. While worldwide demand exceeds 92 million barrels per day, the drop in price from over $105 this past summer to under $50 translates into sizable savings for the average American.

Who Gains vs. Who Loses

Spread out across all industries, U.S. consumers could be looking at an extra $300 billion in savings this year, since oil touches just about every aspect of daily life in one form or another.

The working poor, in particular, will be the largest beneficiaries, since energy expenses constitute a greater percentage of household income for them than for any other group. They will likely feel as though they are getting ahead, for a change, rather than continuing to slip further into the abyss.

The impact of “less pain at the pump” is closely correlated to positive confidence figures. When the general public is confident, spending shifts to larger and more discretionary purchases, creating a positive feedback loop. This loss of confidence is a large part of what the Fed has been battling since Depression 2.0 began. In order to begin a real recovery, those with tight wallets must feel that safer conditions merit some loosening. Just how important this development really is becomes evident when recognizing that more than half the working population is making less than $30,000 a year.

Already, sentiment has drastically changed, which can help explain much of the improvement in the President’s recent approval numbers, surging upwards by more than 22 points since the November midterms. Low gas prices make people very happy, and happy people tend to spend money.

There will be huge losers to make up for the public’s big win. Many states heavily reliant on the oil sector—states which for years benefited from the much higher manipulated prices—could now be facing economic and social collapse if the lower prices drag on for any significant period of time. The duration of this downturn is the key to how the geopolitical and economic inversion plays out between consumers and producers. It’s like a hot stove: touch it for a short time and you’ll fare all right, but hold your hand there for a while and you’ll be badly burned.

Large crude oil suppliers, like Saudi Arabia, Russia, Venezuela, Canada, and even the great state of Texas, are now in flux as budgeted revenue streams dry up. Most major Wall Street sources are calling for the excess supply to last for the next 12-18 months. But what if they are wrong, just like they were wrong before the prices began to crash?

Supply and Demand

The world’s current demand is estimated to grow from 91.39 million barrels a day to 92.39 in 2015. This daily overcapacity seemingly will add no more than 800K to 1.5 million barrels to the preexisting record level supplies, for the time being.

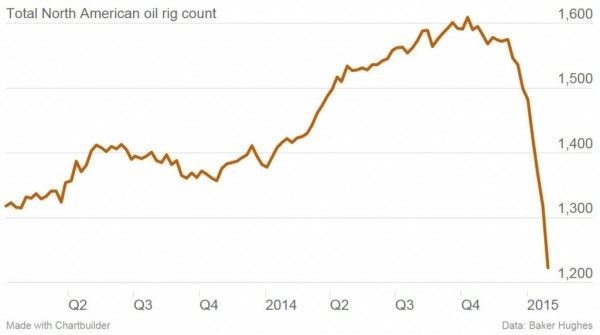

Future production numbers are highly suspect now that U.S. and Canadian firms are aggressively reducing new drilling. Since 2005, it has been North America’s horizontal drilling and fracking firms which have been responsible for much of the new supply (thank you, Texas, Canada, and the Dakotas). These roughnecks are quick and nimble operators compared to most national oil companies and private industry giants. Unfortunately, the fracking-enabled oversupply, which is being taken for granted, could easily disappear within six months.

The fact that a small 1 to 2 percent (maximum) oversupply has led to a correction in crude oil prices of more than -50 percent is not normal. Price declines of this magnitude can easily reverse if demand increases by just 2 percent in response. With much of the world’s increased demand coming from third world countries, rather than mature economies, the sensitivity to lower prices is amplified to the upside as poorer people of the world change their day-to-day usage.

Emerging markets’ auto sales could be the canary in the coalmine as to what’s to come. A small percentage change in sales volumes in markets as large as India and China involve millions of potential new drivers with tanks to fill. The real question going forward is this: how long before the next shortage develops, sending prices higher?

Wall Street Pundits are Wrong Again

The tectonic shift in prices has caught the entire world by surprise. Next to no one saw this coming this past summer (watch CNBC YouTube clips if you don’t believe it). No major publicly known player was calling for this type of correction. No one. Many of the so-called “experts” that were paraded out last spring kept forecasting stable or higher prices. No one claimed prices would fall below $45 a barrel, so why would anyone listen to these experts’ predictions now?

Geopolitical Aspects

Many governments around the world owe their very existence to the presence of abundant crude supplies within their borders. Without the constant inflow of oil revenue, their ability to function economically will be severely impaired, as they’re essentially one-trick ponies.

Economists, for decades, have written about the curse of oil wealth and how it creates these dependent societies that have no other means to generate wealth. In fact, over 30 percent of Saudi Arabia’s population is foreign workers who, in many ways, function as serfs. Recently the Kingdom decided to increase the bribes to its citizens by an additional $30 billion to keep the Saudi family in power. There are limits to this official practice, as budget surpluses quickly turn to budget deficits.

Excess is too mild of a word to describe the situation in many Middle Eastern countries; much of their society doesn’t even work in a traditional sense. How will these countries, those which rely on guest workers, pay their bills on half a paycheck? Many could, with time, look like ghost towns, as the Golden Goose of high energy prices stops laying eggs.

Those OPEC members that are burdened by higher production costs than the others are already at a breaking point, with Venezuela teetering on the edge of collapse. If just one of these weaker states falls into chaos, the oversupply could quickly become a severe shortage, to say nothing of the risks of ISIS. The President should be topping off the Strategic Petroleum Reserve by adding another 36 million barrels to the existing spare capacity as a precaution. Half-off sales usually don’t last very long.

In the past, when prices were too low for OPEC’s members to pay their sovereign obligations, Saudi Arabia could always be counted on to reduce supply in order to prop up the market. This burden fell on Saudi Arabia because other members could never be counted on not to cheat.

What the Saudis did was outright manipulation, a crime which would land you in jail in the U.S. Arresting the heads of state who currently supply one-third of the market’s daily demand wouldn’t be easy, so they can get away with it.

Economics of Oil Production

The conventional oil fields of the world (which are dwindling in number as well as production totals) deplete at around a 5 percent rate per year, with a 50 percent recovery rate. The new fracking fields deplete at over 50 percent in the very first year, and recover less than 10 percent. This means that over 90 percent of the tight oil freed by fracking and horizontal drilling is left behind. Supply is always available for the right price, but because of the manipulation of the past, no one really knows what the real price would be—until now.

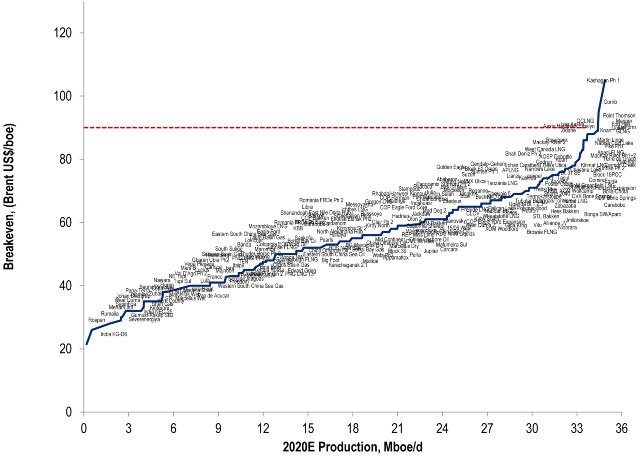

Saudi Arabia’s refusal to decrease production has opened the formerly closed market to price discovery. Having each country and company producing without the safety net of price support should clear out the marginal players very quickly. It appears that $82 a barrel is the industry’s magic number to render added supply economical, given current demand, but no one can really know for sure until producers are put to the test.

Below are the typical production costs for a barrel of oil, taken from various sources:

● Middle East $27

● Offshore Shelf $41

● Heavy Oil $47

● Onshore Russia $51

● Deepwater $52

● Ultra Deepwater $56

● North American Shale $65

● Oil Sands $70

● Arctic $75

Here is a chart from Citi that is a bit more specific. The key is to understand that those extra barrels cost significantly more as demand increases at the end of the curve.

Citi (Full Size)

The new sources of supply that the world is counting on will not last without heavy investment. The flaring rigs lighting up the Dakota nights’ skies burn bright—but have very short lives.

Although technology is forcing the costs of extraction lower, much like Moore’s Law doubles computing power every few years, the days of simply drilling a shallow well and tapping into the next Ghawar for pennies on the dollar are essentially over.

New supply is like the difference between planting an apple tree and planting corn. Conventional apple tree fields have upfront costs and minimal upkeep, but the supply lasts decades. On the other hand, corn and fracking fields require constant high investment in order to maintain supply.

This merry-go-round of constantly having to replenish world demand with fracking rather than conventional sources significantly drives overall costs higher. The Peak Oil believers from a few years ago were not wrong as much as they were off in their assumptions.

There is no Peak Oil, just Peak Low Cost Oil. There will always oil available as new sources are constantly found and technology advances. This reality is best represented by an upward sloping parabolic curve. The variable, once prices reach equilibrium, is what will the next additional barrel cost in the future?

The once bitten, twice shy lenders are well aware of the pricing structure of additional supply, but they are being forced to readjust their models to reflect the higher volatility and added risk.

Much like the Internet crash and housing bubble, what were once viewed as sure things are now seen as a possible financial Ebola, where every cough of borrowers will be seen as a possible death sentence for loans that are souring.

Borrowing costs are going up. A year ago, a bank that would have loaned money to a firm with the market price at $80 a barrel, may today require a $100 price as a condition on the very same project. This added risk premium should lead to much higher future prices, exceeding what saber rattling from Iran ever could. Many firms that were once viewed as prime credit are now seen as junk bond time bombs that could explode at any time. Bankers are nervous.

How much does your home insurance bill go up after a hurricane? This storm of low prices may set in motion a vicious cycle whereby we could be facing a painful rebound as existing supply fails to be replaced. Future financing terms on energy projects will most likely require much higher oil prices, as well as carry much higher interest costs, to compensate for the increased instability. Bankers don’t like to gamble, and taking steps to mitigate as much risk as possible will build in a new higher cost to future production.

Short of some earth-shattering technological energy alternative, the increase in future oil supply will be heavily dependent upon higher and higher investment costs. The world, which will never run out of oil (cheap oil is another story), continues to consume more and more energy each year. The public must remember that in order to keep the supply steady and less volatile, the constant reinvestment merry-go-round must be maintained.

Consumer Behavior is Changing FOR THE WORSE

Consumers should not get comfortable with current pricing. By this December it appears that prices could once again rise above the magic $80 a barrel, as new supply fails to materialize and demand heats up across the globe.

U.S. consumers in December 2014 used over 4 percent more oil daily than they had a year earlier. This increase works out to be an extra 800,000 barrels per day, which, if continued at the same pace through the rest of the year, will make the IEA’s forecast almost a million barrels too low.

Consumers appear to be getting too comfortable with $2.00 a gallon gas. Data shows that $3.00 a gallon is the tipping point for Americans’ choice in vehicle type. With current prices being so low, it should not come as a surprise that SUV sales are increasing and electric vehicle sales are slowing. Unfortunately, these current purchases don’t reflect a scared consumer but instead a naïve one who is assuming low prices will last over the life of their new gas guzzler.

Figures in the next quarter of boat and RV sales, along with airline travel, should be closely monitored. Once these types of purchases start increasing significantly, then you know the public has grown complacent in the face of current tolerable gasoline prices.

What Does This All Mean?

The last seven months have been a financial game of chicken between the old-school crowd in the Middle East, and the roughneck frackers of North America, who are now rewriting the playbook of the last half-century. As commercial hedges fall off, and nimble North American production shuts down, the Invisible Hand of the marketplace will finally be free to disclose the real price of oil that has been hidden by OPEC’s grasp. At the end of the day, it will be the American public that will come out the big winner. We will finally learn, after more than 40 years of not knowing, what the free market supply/demand price of crude truly is. This knowledge will make it harder for secretive governments and corporations to manipulate prices in the future, while strengthening domestic production to weather supply shocks in the future.

Author’s note: This article in no way should be viewed as a solicitation to buy or sell any security.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.