Here’s a headline that got some attention—and might cause some mental whiplash: “Senate GOP to add repeal of Obamacare insurance mandate into tax bill.”

That was The Washington Post, but other media outlets, too, are running with the story.

Yes, the Obamacare issue is ba-a-ack. Congressional Republicans could, in fact, be voting on the fate of the program — formally known as the Affordable Care Act — within days.

This prospect is, indeed, causing some necks to feel some serious torque. As we all remember, for most of 2017, the Republicans — President Trump and the GOP majorities in both chambers of Congress, plus many pundits and millions of activists — were preoccupied with “repealing and replacing.” All those efforts fell short, although just barely; who can forget Sen. John McCain’s wee-hour thumbs down in July?

Even after that, the Republicans persisted, mounting another effort, the so-called Graham-Cassidy bill. Yet that close-but-no-cigar effort faltered at the end of September, and so finally, it seemed, the GOP feeling was, Enough is enough. It was time, most Republicans said, to “pivot” to tax reform.

Well, that was then. Now, all of a sudden, the issue is front-and-center. On Tuesday afternoon, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said, “We’re optimistic that inserting the individual mandate repeal would be helpful” to the tax-reform push.

So, is McConnell correct? Can the inclusion of the individual-mandate repeal help the GOP get over the finish line on tax reform? Short answer: Leading Republicans seem to think so, and they’ve got a lot riding on it.

And as for the Obamacare mandate itself? Well, we all remember the mandate. It’s the legal requirement that people have health insurance. In fact, when most people think of Obamacare, they probably think first of the mandate, whether they love it or hate it. To Republicans, it’s a nasty abridgment of freedom, while to Democrats, it’s the kindly archstone of Obamacare’s architecture.

Fewer than one in ten Americans gets their health insurance through the individual market (KAREN BLEIER/AFP/Getty Images).

Yet, in fact, the most expensive portion of Obamacare is something else entirely: the expansion of Medicaid. In fact, because the Medicaid expansion is the biggest outlay, it became the focus of Republican repeal-and-replacers earlier this year. The aforementioned Graham-Cassidy bill, for example, was characterized by a clever rethink of the Medicaid issue, block-granting Medicaid to the states. Block grants, of course, are central to the ideal of federalism, much beloved by Republicans.

Okay, so now, where is the latest flurry of tax and healthcare activity — this new flurry on top of all the other flurries — headed? Here are eight quick points:

First, it’s important to realize that Republicans really, really want a tax reform bill to pass. We can shovel in the clichés — “failure is not an option,” “make or break,” “hell or high water” — because they all apply. And if, along the way, tax reform turns into a simple tax cut, well, that’s okay with the GOP. As the late conservative pundit Robert Novak liked to say, “Republicans were put on this earth to cut taxes,” and elephants agree.

Second, with that tax-cut determination — some would say desperation — in mind, it might seem counterintuitive to now add the mandate-repeal into the mix. That is, why add a new level of complexity? However, Capitol Hill Republicans calculate that there’s more to be gained by including the mandate-repeal, because it will rally Republicans. Hopefully this will include such notoriously finicky figures as Sen. Rand Paul, who never seems to think that anything is pure enough for him. If Paul becomes a guaranteed “aye,” well, the mandate-repeal gambit might well be worth it.

Rand Paul knows the healthcare system as a doctor and now, after suffering a sneak attack by a neighbor, as a patient (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais, File).

Okay, and so what of the moderates? You know, such Senators as Susan Collins and Lisa Murkowski, who have been “nay” votes on Obamacare repeal in the past? Well, the mandate question is different than the Medicaid question; the mandate can be defined as a “liberty” issue, whereas the Medicaid expansion was regarded as more of a “compassion” issue. So, will Collins and/or Murkowski — or who knows, maybe even John McCain — now get on board?

On Wednesday, Collins indicated her concern about the mandate elimination, but she didn’t seem definitive. Also on Wednesday, and for different reasons, Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin announced that he was opposed to the bill. Is that his final answer? Or was it just a shrewd poker-playing move? There’s no way to know. All we know for sure is that the Congressional deal-making bazaar is open, and it will be running 24/7 for a good, long time.

Third, it’s important to recognize that this new plan affects only the mandate aspect of Obamacare. To be sure, that’s a big chunk of change: hundreds of billions of dollars over a decade. And Republicans figure that if the mandate to buy insurance is repealed, then federal funds that supplement such purchases will be obviated, too, and that helps make the tax cuts more affordable, by holding down the deficit.

Indeed, Sen. John Thune of South Dakota, the third-ranking Republican leader, as well as a member of the tax-bill-writing Finance Committee, told the Post that the savings from mandate repeal would allow the GOP to cut taxes even deeper:

It’ll be distributed in the form of middle-income tax relief. It will give us even more of an opportunity to really distribute the relief to those middle-income cohorts who could really benefit from it.

So thus we see the Republican philosophy in its essence: If the federal government spends less, it can tax less. And lower taxes are good for jobs and growth.

Yet at the same time, under this latest GOP plan, the rest of Obamacare would be unaffected. That is, not only the Medicaid expansion, but also the constellation of agencies and programs that arose with Obamacare, including such obscure-but-powerful entities with funny names such as IPAB and PCORI. So as we can see, the hoped-for repeal of the mandate is only a partial repeal of Obamacare. To which Republicans might say, We have to start somewhere. Think of this as a down payment.

Indeed, Republicans believe that if they can get the tax bill through, then they are more likely to do well in the 2018 midterms. And if they hold on to their majorities, then they can take more bites out of the Obamacare apple in the next Congress.

Fourth, speaking of elections, the inclusion of the mandate-repeal will energize many Republicans. After all, for seven years now, just about every conservative ideological hub and donor group has been eager to move ahead on repeal-and-replace. And so if even if this is just a partial repeal, well, that still counts as a victory — certainly, it’s more than the GOP has now. For sure, President Trump will be a happy man, and Republican lawmakers have learned that they are better off when he is happy.

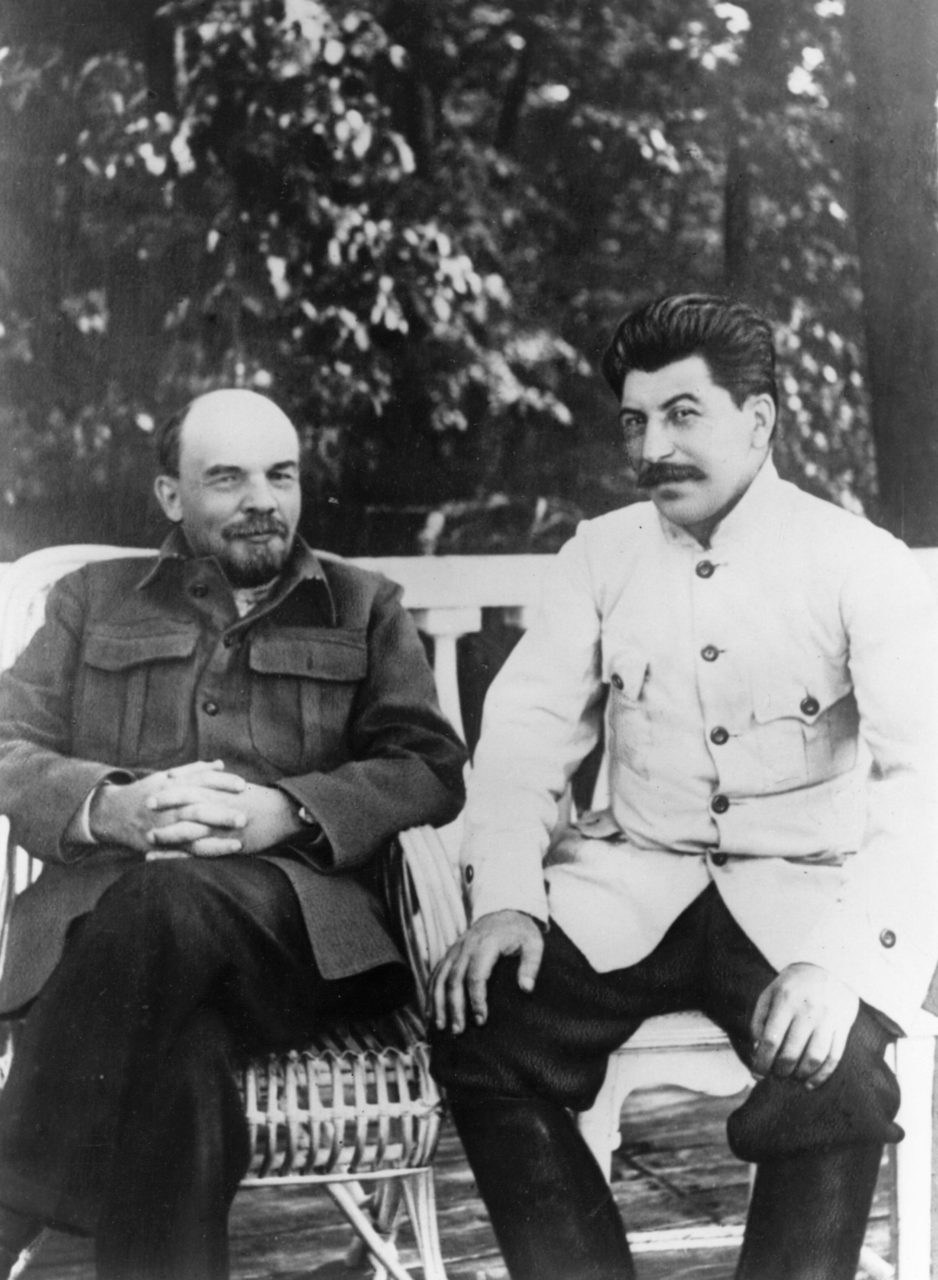

As we know, in politics, there’s a lot to be said for uniting your team. As the Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin (not a Republican, but a shrewd enough politician), always said, Power is mass multiplied by cohesion. So today, combining the issues of tax reform and Obamacare repeal could help Republicans cohere—that’s the hope, anyway.

Soviet Communist leader Joseph Stalin (1879 – 1953), right, with Soviet leader Vladimir Ilyich Lenin (1870 – 1924), in Gorky (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images).

Fifth, the inclusion of the mandate-repeal kiboshes any real prospect that a Democrat — even a single one — will vote for the tax bill. Of course, it seemed unlikely before the inclusion that any Democrat would vote for the bill, so Republicans figure they have nothing to lose. If they can cohere, Republicans have the votes; they don’t need the Democrats.

Sixth, despite all the premeditation, there’s no guarantee that Republicans have made the right calculation as to how to wrangle the votes needed to pass a tax bill. McConnell has had a good reputation as a vote-counter, but that reputation took some hits in the bellyflops of the last year. As they say, the proof is in the pudding — and we’ll know about the pudding soon enough

Yet, even if the Republicans were to lose a vote on this tax bill, they’ll have another. This session of Congress, after all, is less than half over. Indeed, the landmark 1986 Tax Reform Act, to which this legislation is often compared, was not signed into law by President Ronald Reagan until October 22, 1986 — that is, at the tail end of the 99th Congress, with just three months to spare.

So today, the leaders of the 115th Congress know that they have, if need be, another fourteen months — until January 2019. Yes, they shudder at the thought that it might take them so long to get it done, but they shudder more at the thought of not getting it done at all. In the meantime, it’s their fervent hope that they put the tax issue happily to bed by Christmas 2017.

Thus we can see: If they lose a vote, they’ll have a second vote, and a third, and so on, hopefully this year, but if they need to, next year, too. With each iteration, of course, they’ll likely change something, trying to get it just right—or at least good enough.

Seventh, sometimes lawmakers vote one way, and then later, after reflection — or more pressure — they vote the opposite way. That is, they vote to make a point, perhaps just to get the matter off their chests, and then they reassess. A case in point is the 1990 tax increase, the one engineered by President George H.W. Bush in defiance of his “read my lips, no new taxes pledge.” The tax hike was wildly unpopular among most Republicans, and so they voted it down on October 1, 1990. And yet just three weeks later, as the pressure mounted, many Republicans switched, and the bill passed. As they quip on Capitol Hill, if Members feel the heat, they’ll see the light (We can look back and see that the Bush 41 tax hike was a failure, both politically and economically, but at the time, many Republicans believed that all that mattered was getting it done — effective vote-whipping is oftentimes a matter of stampeding the herd.).

Eighth, it’s important to understand that all these topics are still mostly up for grabs. That is, when the political sausage goes into the legislative meat-grinder, anything can come out the other end. Yes, Republicans want to find a way to cut taxes, but everything else is negotiable, including the question of mandate-repeal, or not.

As we have seen, for Republicans, the main thing is to get the tax cut through. They believe strongly — and history, including the history of the Reagan years, supports this belief — that the resulting economic growth will boost them in 2018, and beyond. And so GOPers, if they have to, will consider all the possible options and permutations — flat or round, six or a half-dozen, animal, vegetable, or mineral.

Okay, so those are eight points to ponder. And now, here’s Virgil’s bottom line: He’ll be very surprised if the Republicans don’t get their tax bill through.

Yes, the GOP has fallen short in the past — wall, anyone? — but this is different: This is about taxes. And as we have seen, Republicans really care about taxes.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.