This year marks the 100-year anniversary of some of America’s greatest battles in World War I. In many ways, this has become a forgotten war, a little-known piece of history that few people understand.

But the Doughboy generation who fought in that war included some of our nations’ greatest heroes, including thousands of Native American warriors who volunteered for some of the war’s deadliest and most critical missions.

One of the most fearless of those American Indian Doughboy soldiers was Corporal Thomas D. Saunders of the 2nd Engineer Regiment.

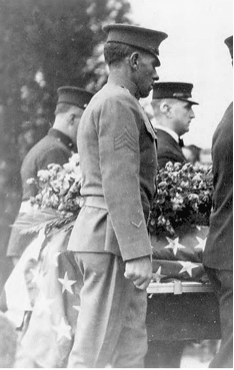

Corporal Thomas D. Saunders carrying the casket of the Unknown Soldier Image Source: USMC

While it was still dark on the morning of September 12, 1918, Saunders slithered through the mud of no man’s land on the Western Front with just one fellow soldier, Private Alfred Wilkerson, at his side. Tracer rounds lit up the sky overhead as German machine gunners trained a torrent of lead at the American lines. With rain pelting their faces, Saunders and Wilkerson inched their way toward their target: the seemingly endless coils of rusty barbed wire that formed a nearly impenetrable barrier guarding the German trenches several hundred yards away.

The two had volunteered for a virtual suicide mission: snipping the wire to create a path for the American troops to reach the enemy.

The story of that daring mission is retold in my bestselling book, The Unknowns: The Untold Story of America’s Unknown Soldier and WWI’s Most Decorated Heroes Who Brought Him Home. Released in May, The Unknowns follows eight American heroes who accomplished extraordinary feats in some of the war’s most important battles. As a result of their bravery, these eight men were selected to serve as Body Bearers at the ceremony where the Unknown Soldier was laid to rest at Arlington Cemetery.

One of those Body Bearers was Saunders, a member of the Cheyenne Tribe from Medicine Bow, Wyoming. On May 12, 1917, at the age of 25, Saunders had enlisted in the U.S. Army and soon became one of the approximately 10,000 American Indians who fought in World War I.

Both sides of the conflict revered the Indian warriors. Legend suggested that Indians had otherworldly abilities to move silently through the forest, find their way in the dark, travel long distances with limited rest and food, and defeat any enemy in hand-to-hand combat. While these stereotypes were more myth than reality, Native soldiers frequently distinguished themselves when serving as scouts, messengers, and combat engineers. They also sometimes served an invaluable function by transmitting radio messages in their tribal languages, which were undecipherable to Germans who might intercept the calls. And at the time, Germans had a fascination with American Indians that some have called “Indianthusiasm.” They flocked to Wild West Shows, which inflated the Natives’ reputations as epic warriors. So when they met Indians on the battlefield, many Germans were primed to believe the American Indians were all but invincible.

On September 12, the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), led by General John J. Pershing, launched an attack against German forces near the town of St. Mihiel, France. It was the first real test for the United States in World War I, a chance to prove themselves to their European allies, who largely viewed the Americans as bungling novices who knew little about the art of war.

But before that assault could begin, Saunders and Wilkerson had to clear the way.

Using heavy, two-handled wire cutters, the duo painstakingly snipped through the nests of wire, one at a time. For hours, they toiled in the darkness, muscles bulging as they strained at their task while enemy machine gunners and artillery tried to take them down.

As dawn began to cast its glow on the gray, trench-covered landscape, Saunders and Wilkerson cut through the last piece of wire.

But their job was far from done.

They were fighting engineers, which meant that as soon as they were finished with their wire cutters, they drew their weapons and headed for the German trenches, becoming some of the first Americans to cross the German lines at St. Mihiel.

Leading a small group of men, Saunders fought his way forward toward the hamlet of Jaulny. There, the Germans had set up a barracks and hospital in the Château de Jaulny, a massive stone castle constructed in the second century on the high ground near a river.

As the men pressed deeper behind the lines, machine-gun and sniper fire grew increasingly intense. Striking ahead on their own, Saunders and Wilkerson doggedly advanced toward the castle, bounding through trenches and foxholes as bullets whizzed by on every side. They soon encountered a dugout manned by eight Germans, whom the Americans took prisoner. Not yet satisfied, the pair continued on toward the château.

Heedless of their own survival, the two Americans cautiously entered the stone edifice, and they cleared the structure, taking prisoner everyone they found. Remarkably, the two men rounded up 55 more prisoners in the castle and the town, bringing their total for the single day to 63.

For their accomplishment, Saunders and Wilkerson received the Distinguished Service Cross. The AEF achieved an unequivocal victory at St. Mihiel, placing the Germans off balance and setting up the coming battles in the Meuse-Argonne and Blanc Mont Ridge, where Saunders was once again decorated.

As the war progressed, Saunders participated in several more battles, frequently displaying courage that set him apart from his fellow soldiers. One of his commanding officers would later write, “Such heroism is understood by a man’s comrades more than can be explained in writing, as during time of stress, the one who does what Saunders did, does it with no thought of self, but only of carrying out to the best of his ability what he believes his duty to be. In my close contacts, during and since the World War with Saunders, I can state that everything he does is a bit better and with more energy than other men of equal physique would do the same thing.”

Saunders became one of the most highly decorated American Indian soldiers in World War I, and he proudly took his place as a Body Bearer at the ceremony to bury the Unknown Soldier.

At that memorial, another Native American, Chief Plenty Coups, also honored the Unknown Soldier and all the American Indians who had served in the war by placing his feathered war bonnet and coup stick in the sarcophagus alongside the body. He then addressed the crowd, saying:

I am glad to represent all the Indians of the United States in placing on the grave of this noble warrior this coup stick and war bonnet, every eagle feather of which represents a deed of valor by my race. I hope that the Great Spirit will grant that these noble warriors have not given up their lives in vain and that there will be peace to all men hereafter. This is the Indians’ hope and prayer.

That prayer for peace on earth has yet to be answered, but it remains a fitting dream a century after the end of the first World War. Perhaps in remembering the actions and sacrifices of the men who took part in that conflict, we can move closer to that worthy goal.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units. He is the author of eleven books. The Unknowns is his newest, and it is featured in Barnes & Noble stores nationwide. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah and speaks often on espionage, special operations, and counterinsurgency. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries Band of Brothers and for documentaries produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. @combathistorian

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.