Now that the 2018 midterm elections are in the rear-view mirror, candidates are gearing up for the 2020 presidential election. So here comes … Elizabeth Warren.

As we all remember, her recent attempt to get the “Pocahontas” issue out of the way didn’t work out too well–leading some to wonder whether she could ever be White House material. Yet even so, despite weakening poll numbers, Warren has persisted; she is, after all, a U.S. Senator and an important intellectual force in the Democratic Party.

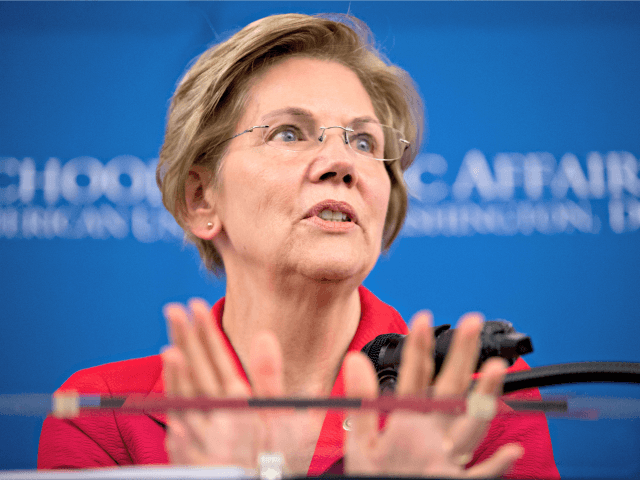

Thus Warren’s “major” foreign-policy speech at American University on November 29, as well as her accompanying article in Foreign Affairs, has received respectful notice in the MSM.

CNN, for instance, gave her a generous headline: “Introducing: The Warren Doctrine.” Reporter Chis Cillizza described her speech as “peppered with references to international trade, war, and a more progressive foreign policy tack overall,” adding, “the Massachusetts senator flexed her foreign policy bona fides—a critical move for any would-be presidential candidate.”

Of course, since she’s running as a Democrat, Warren attacked Donald Trump aplenty. As she said of the 45th president, “He embraces dictators of all stripes. He cozies up to white nationalists. He undermines the free press and incites violence against journalists.”

Yet even so, what was notable to this observer was the relative absence of Trump-bashing; that is, Warren seems to have a bigger target in mind than Trump—namely, all the presidents of the last three decades: “While it is easy to blame President Trump for our problems, the truth is that our challenges began long before him.” She added, “And without serious reforms, they are just as likely to outlast him.”

Then Warren warmed to the real point of her speech, which was an all-out attack on globalism, or, as she called it, “neoliberalism.” Sweeping over the last three decades, she declared, “U.S. trade and economic policies have not delivered for the middle class. … The trade deals they negotiated mainly lifted the boats of the wealthy while leaving millions of working Americans to drown.”

In particular, she scorned the North American Free Trade Agreement, which was pushed into enactment by her fellow Democrat, Bill Clinton. “NAFTA,” she jibed, “has already cost us nearly a million good American jobs.” Moreover, she had nothing good to say about follow-on trade bills supported by Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

Of course, these trade deals have all been scorned, too, by the current president. And so, as Warren blasted away on trade, it was hard not to think that she sounded a bit like … guess who.

Indeed, by some reckoning, Warren even sort of out-Trumped Trump. Notably, she came out strongly against the Trump administration’s new US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which she labeled “NAFTA 2.0.” As she put it, “NAFTA 2.0 has better labor standards on paper, but it doesn’t give American workers enough tools to enforce those standards. Without swift and certain enforcement of these new labor standards, big corporations will continue outsourcing jobs to Mexico so they can pay workers less.”

As the headline in the left-leaning Vox observed, “Elizabeth Warren wants to outflank Trump on trade.” And in a sub-headline, Vox added some distinctly loaded words: “The Warren Doctrine on trade: America first.” Writer Matthew Yglesias explained, “Warren unloads a biting critique of a generation’s worth of neoliberal trade policy consensus in Washington and—strikingly—insists that despite Trump’s embrace of protectionist rhetoric and aspects of protectionist policy, he hasn’t gone nearly far enough.” [emphasis added]

To be sure, plenty of Democrats have always opposed free-trade deals. It’s just that they were outshined by the Clinton-Obama-style globalists—at least until Trump exploded the issue in the ’16 campaign, pushing globalism into eclipse. So now anti-free-trade Democrats are liberated to compete with anti-free trade Republicans.

Still, Warren is nothing like an economic nationalist. As she also said in her speech, “Democracy is running headlong into the ideologies of nationalism, authoritarianism, and corruption.” Got that? In Warren’s view, nationalism is an obstacle to democracy. (That opinion runs contrary to the thinking of, say, Theodore Roosevelt or Franklin D. Roosevelt, but that’s a debate for another time.)

Indeed, Warren is best described as a true-blue liberal; she received a 100 percent rating from Americans for Democratic Action.

Yet even so, much of what Warren had to say sits well enough with the post-Bush-43 Republican Party. For instance, she slammed the 2003 invasion of Iraq, which, she said, “destabilized and fragmented the Middle East, creating enormous suffering and precipitating the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people.”

Here we might pause to note that not only was Warren trashing W., but she was also trashing some top Democrats who supported the war and might be ’20 rivals, including Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, and John Kerry. Indeed, she added, “It’s time to seriously review the country’s military commitments overseas, and that includes bringing U.S. troops home from Afghanistan and Iraq.” (Speaking of these dead-end wars, there’s at least some evidence that Trump feels pretty much the same way.)

Moreover, Warren offered no love for any of the “liberal hawk” interventions of the past quarter-century—that is, the Democratic-ordered military operations, from Somalia to Kosovo to Haiti to Libya. Nor did she say anything nice about possible future interventions, in places such as Darfur or Syria. In fact, she never even mentioned the word “humanitarian.”

Indeed, Warren made only a brief mention of immigration, arguably the hottest topic among Democratic activists. She spoke only of “immigration policies to yield a more robust economy and a more diversified work force.” Admittedly, a hypothetical President Warren could interpret those words, er, liberally, and yet she seems aware that open-borders-ism has a deep downside. She allowed, “Widespread migration of millions of people seeking safety from war-torn regions has allowed right-wing demagogues to unfairly blame the newcomers for the economic pain of working people at home.” We might step back and observe that here Warren sounds a bit like Hillary Clinton, who said just recently that unchecked migration was sure to boomerang on the left.

So it’s interesting to consider all the left-friendly words that Warren did not use in her speech, such as “asylum,” “ICE,” “gay,” “gender,” “Africa,” and “AIDS.”

Indeed, she mentioned “foreign aid” only once. And while she did call for beefing up the State Department and relying more on diplomacy, she was hard-nosed even then, saying, “Diplomacy is not about charity; it is about advancing U.S. interests and preventing problems from morphing into costly wars.”

Once again, Warren is no kind of conservative; she called for a deep cut in the Pentagon’s budget, even as she strongly praised arms control. And oh yes, she’s big on fighting climate change.

Yet still, Warren’s speech and article tell us that she is something of a foreign policy realist. As such, she is refreshingly at odds with the recent utopian presidents, on the left and on the right. After all, it wasn’t that long ago that Barack Obama, having just won a Nobel Peace Prize for doing nothing, was speaking dreamily of abolishing all the world’s nuclear weapons. Were the Chinese—or the Iranians—ever going to go along with such disarmament? And just a few years earlier, George W. Bush was heard rhapsodizing, “We have a calling from beyond the stars to stand for freedom.” Beyond the stars—really?

By contrast, Warren, is obviously focused on the economy, and so her foreign policy agenda is subordinated to domestic concerns. That is, she has the realistic view that, high hopes notwithstanding, the U.S. is inevitably limited in what it can do around the world.

So that leaves us with the distinct feeling that she shares at least some foreign-policy ideas with … him.

###

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.