One of the many remarks apocryphally attributed John Maynard Keynes has the British economist saying, “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

To the best anyone has been able to determine, Keynes never spoke those words. They appear to have their origin in a 1970 appearance by American economist Paul Samuelson on the television show Meet the Press in which the topic of inflation was discussed.

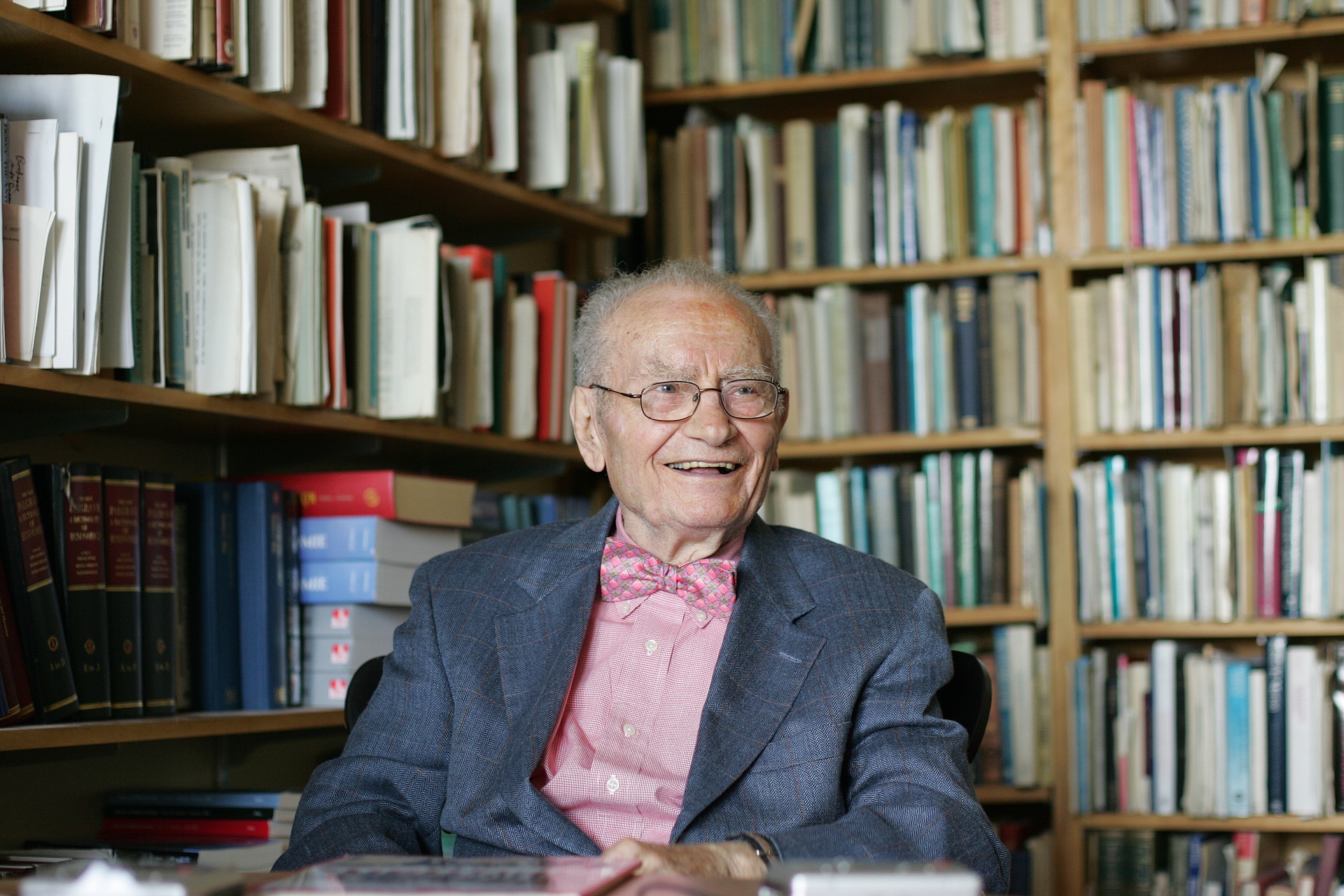

Paul Samuelson, the first American to receive the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. (Rick Friedman/Corbis via Getty Images)

Samuelson was the author of what might be the best-selling economics textbook of all times, Economics: An Introductory Analysis. Samuelson’s book appeared in numerous editions in the years that followed its original publication in 1947 until its final version in 2009, the year its author shuffled off his mortal coil. Over the years, Samuelson’s estimate for the level of inflation that was healthy for the U.S. economy shrank from five percent, to three percent, and eventually to two percent.

On Meet the Press, Samuelson pointed out that this shifting of the inflation goal post had caused some complaints. Most notably, the Associated Press had published an article titled, “Author Should Make Up His Mind.” The economist insisted he was well within his rights to change his analysis as updated information became available. “When events change, I change my mind. What do you do?” Samuelson said.

This is what happened to the Federal Reserve last month. Fed officials had been unusually clear and specific about their plans to approve a half-point hike in their interest rate target. Unlike their predecessors led by Fed chairmen like Paul Volcker or Alan Greenspan, the current crop of Fed officials believe it is extremely important to prepare the market for their interest rate moves. The idea is that this prevents surprises that can send financial markets into turmoil.

Even though Fed officials had officially abandoned the talk of inflation being “transitory,” many apparently still believed some version of the idea that inflation would fade on its own. Indeed, many economists thought that inflation had peaked in March at 8.5 percent. They expected a kind of “immaculate disinflation” to take hold, gently bringing down the rate of inflation with mild Fed hikes, a minimal uptick in unemployment, and growth more or less continuing near what Fed officials think of as its longterm potential. A slight decline in April, with month-0ver-month inflation picking up just 0.3 percent, greatly encouraged them in this view.

Members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors pose for a group photo on May 23, 2022, in Washington, DC. From left to right: Christopher Waller, Michelle Bowman, Chair Jerome Powell, Vice Chair Lael Brainard, Philip Jefferson, and Lisa Cook. (Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The shocks that changed the minds at the Fed arrived on June 10, a Friday morning just a few days before the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) was set to begin its meeting on June 14, the following Tuesday. The first was the Department of Labor’s report on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This showed that prices jumped one percent in May compared with April, the highest monthly rate of inflation in the post-pandemic period apart from March’s 1.2 percent gain. On a year-over-year basis, the index was up 8.6 percent—higher than the misidentified March peak.

The second shock was the upward move in inflation expectations in the University of Michigan’s survey of consumer sentiment. The survey’s results get released twice a month. The first comes out mid-month and is considered a preliminary read. In June, it hit on the Friday before the FOMC meeting. It showed expectations for inflation over the year ahead stood at 5.4 percent, a bit above the May level and matching what was recorded in March and April. Perhaps more disturbingly, the expectation for inflation over the next five to 10 years jumped from three percent to 3.3 percent.

Inflation expectations play a big role in how Fed officials and their staff economists think about inflation. They believe that households’ and businesses’ expectations of future inflation are a key determinant of actual inflation. Critics, including a Fed economist in a paper published just last year, say there’s little evidence that inflation expectations play the causal role mainstream economists assign them. But this remains the dominant paradigm within the Fed.

The minutes of the FOMC meeting released Wednesday noted that “many participants raised the concern that longer-run inflation expectations could be beginning to drift up to levels inconsistent with the 2 percent objective. These participants noted that, if inflation expectations were to become unanchored, it would be more costly to bring inflation back down to the Committee’s objective.”

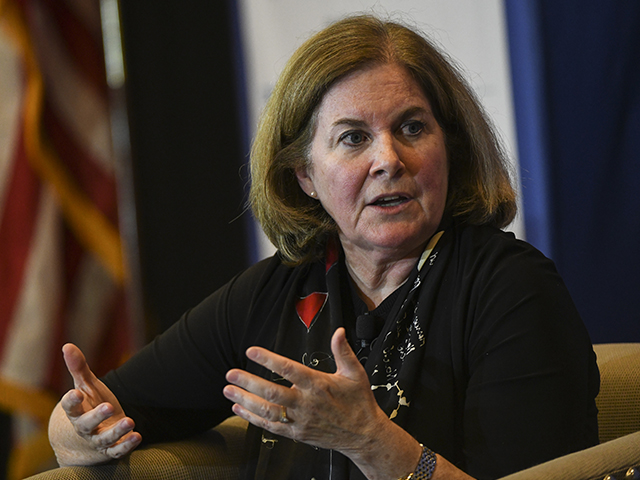

Fed officials decided that a 50-basis point hike would be inadequate given the inflation data that confounded their expectations. They quickly pivoted to a 75-basis point hike and successfully telegraphed this to financial markets—adhering to the No Surprises rule. The minutes showed a strikingly strong consensus for the 0.75 percent move. Not only did 11 out of the 12 voting members of the FOMC agree with the bigger hike, so did every one of the six non-voting participants. Only Esther George of the Kansas City Fed dissented, saying that the Fed was moving too fast.

Could George have been on to something? In the final University of Michigan tally of consumer sentiment, the longer-run inflation expectation was revised down to 3.1 percent, close to the three percent it had been at for months before the jump to 3.3 set off the alarm bells. Indeed, longer-run inflation expectations had been at 3.1 percent back in January. The one-year expectation figure was revised down to 5.3 percent, where it had been in May and below the March and April figures.

Esther George, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, speaks during the NABE annual meeting in Denver, Colorado, on October 6, 2019. (Daniel Brenner/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

It was not just the consumer inflation expectations that were significantly revised. The FOMC minutes repeatedly mentioned the strength of consumption expenditures. “In their discussion of the household sector, participants indicated that consumption spending had remained robust, in part reflecting strong balance sheets in the household sector and a tight labor market,” the minutes said. We now know, however, that consumer spending was much weaker than they thought back at that meeting. Instead of growing at the initially reported 3.1 percent rate in the first quarter, consumption expenditures rose by just 1.8 percent. Consumer spending grew by just 0.6 in April and 0.2 percent in May, less than inflation. Far from remaining “robust,” consumer spending has been contracting in real terms.

In other words, some of the information that went into the Fed’s change of mind in June has turned out to be inaccurate. The Fed could not have known that, of course. What’s more, it may turn out that the Fed’s bigger hike was the correct policy even if it was adopted on a view of economic data that no longer holds up.

One question is whether the Fed’s view will change again now that we have data showing a surprisingly fast deceleration in the economy. The facts are changing again. Can monetary policy keep up?

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.