How the Pilgrims Broke Their Dependence on “Globalization”

The story we tell ourselves about the first Thanksgiving centers on gratitude, providence, and a bountiful harvest. What we forget is why that harvest nearly didn’t happen and what the Pilgrims had to change to make it possible.

The Plymouth Colony’s survival depended on two linked transformations that echo loudly in today’s economic debates: abandoning collectivism for private property and severing dependence on imports in favor of domestic production. The parallel to contemporary arguments over tariffs, reshoring, and economic nationalism isn’t subtle. The Pilgrims quite literally made America work by doing what today’s expert class insists cannot be done.

The Communal Disaster

When the Pilgrims landed in 1620, they operated under terms dictated by their London financiers. Everything produced they produced—food, supplies, labor, housing—would be held in common for seven years, after which profits would be divided between settlers and investors. Private enterprise outside the common stock was effectively forbidden. Everyone received equal rations regardless of contribution. It was, as Governor William Bradford later described it, an attempt at a godly communal “common course and condition.”

It almost killed them all.

The Pilgrim Fathers arrive at Plymouth, Massachusetts, on board the Mayflower in November 1620. Painting by William James Aylward. (Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Kean Collection/Getty Images)Half the colonists died that first winter. The 1621 harvest produced enough for a modest Thanksgiving, but chronic food shortages persisted for two more years. Bradford’s journal captures the problem with clinical precision: able-bodied young men “did repine that they should spend their time and strength to work for other men’s wives and children without any recompense.” Women “deemed it a kind of slavery” to cook and clean for others’ households. With no reward for individual effort, productivity collapsed. By spring 1623, Plymouth faced starvation again.

The colony had ample land. What it lacked were functional economic incentives.

Bradford’s Fix: Distributivism and Private Property

Facing another failed harvest, Bradford made a dramatic break with the collectivist model in 1623. Each family would receive a private parcel of land to farm for that year. Whatever corn they grew, they could keep. It was private property in everything but formal, inheritable title—and the results were immediate.

“This had very good success,” Bradford wrote, “for it made all hands very industrious, so as much more corn was planted than otherwise would have been.” Women who had previously “alleged weakness and inability” to avoid laboring for the common store now “went willingly into the field, and took their little ones with them to set corn.” Bradford noted the irony: forcing them to do this under the old system “would have been thought great tyranny and oppression,” yet with the prospect of enjoying their own harvest, everyone cooperated eagerly.

The 1623 harvest was abundant. Plymouth never again faced the starvation that nearly destroyed it. Bradford was blunt about the lesson: the experience had disproven “that conceit of Plato’s and other ancients” that taking away property and bringing in community into a commonwealth would make people “happy and flourishing.” God’s wisdom, he concluded, “saw another course fitter for them.”

The Importance of Local Production

But Bradford’s reform did more than fix incentives inside the colony. It severed Plymouth’s dependence on England itself.

The original business model assumed heavy reliance on the mother country. Thomas Weston and his fellow Merchant Adventurers would keep the colonists supplied with ships and goods in exchange for control of the venture and a cut of exports. For the first few years, Plymouth lived off imports while struggling to produce enough furs, fish, and other commodities to satisfy its backers.

The Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor, Massachusetts, 1620. Painting by William Halsall, 1882. (Photo by Barney Burstein/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

The shift to private property changed everything. With families farming for themselves, local food production exploded. Within five years, Plymouth had what even mainstream histories describe as a largely self-sufficient economy, meeting subsistence needs through New England farming rather than waiting anxiously for English supply ships. The colony stopped imagining survival as “wait for the next ship from home” and started treating it as “grow our own food here.”

Simultaneously, Plymouth developed its own export base. By 1625, the colonists had established a beaver fur trading operation on the Kennebec River in Maine—the era’s equivalent of a tech startup hitting product-market fit. This became “an essential part of their economy” and the primary means of paying down London debts. In 1627, Bradford and other colonial leaders took over the debts and the fur trade entirely, converting Plymouth from a venture controlled by distant financiers into a self-financing operation run by the people actually doing the work.

The colony shifted from living off the homeland to producing at home and exporting on its own terms.

A Truth So Simple the Experts Always Miss It

A similar story unfolded down in Virginia’s Jamestown colony, which explicitly planned not to grow all its own food but to rely on trade with the Powhatan plus periodic English resupply. When drought hit and supply missions faltered, Jamestown plunged into the Starving Time of 1609–10 and nearly collapsed. After years of chaos, the Virginia Company began granting private plots to colonists in 1618–1619, replacing the old common store with individual farms. Once men were allowed to work their own land and keep the surplus, production rose, hunger receded, and the colony finally stabilized.

The story of the success of Plymouth and Jamestown makes contemporary economists uncomfortable. The Pilgrims succeeded not by optimizing their position in a transatlantic supply chain managed from London, but by building productive capacity on American soil and reducing their dependence on imports. They didn’t wait for comparative advantage to naturally assert itself. They created it.

The modern parallel writes itself. For decades, we’ve been told that domestic manufacturing is inefficient, that supply chains should be optimized globally, and that attempting to reshore production will only make us poorer and drive up inflation. The Pilgrims would have starved if they’d followed that advice. Instead, they planted corn in New England dirt, built their own trading networks, and turned Plymouth from a failing experiment in remote-managed collectivism into a thriving community of producer-owners.

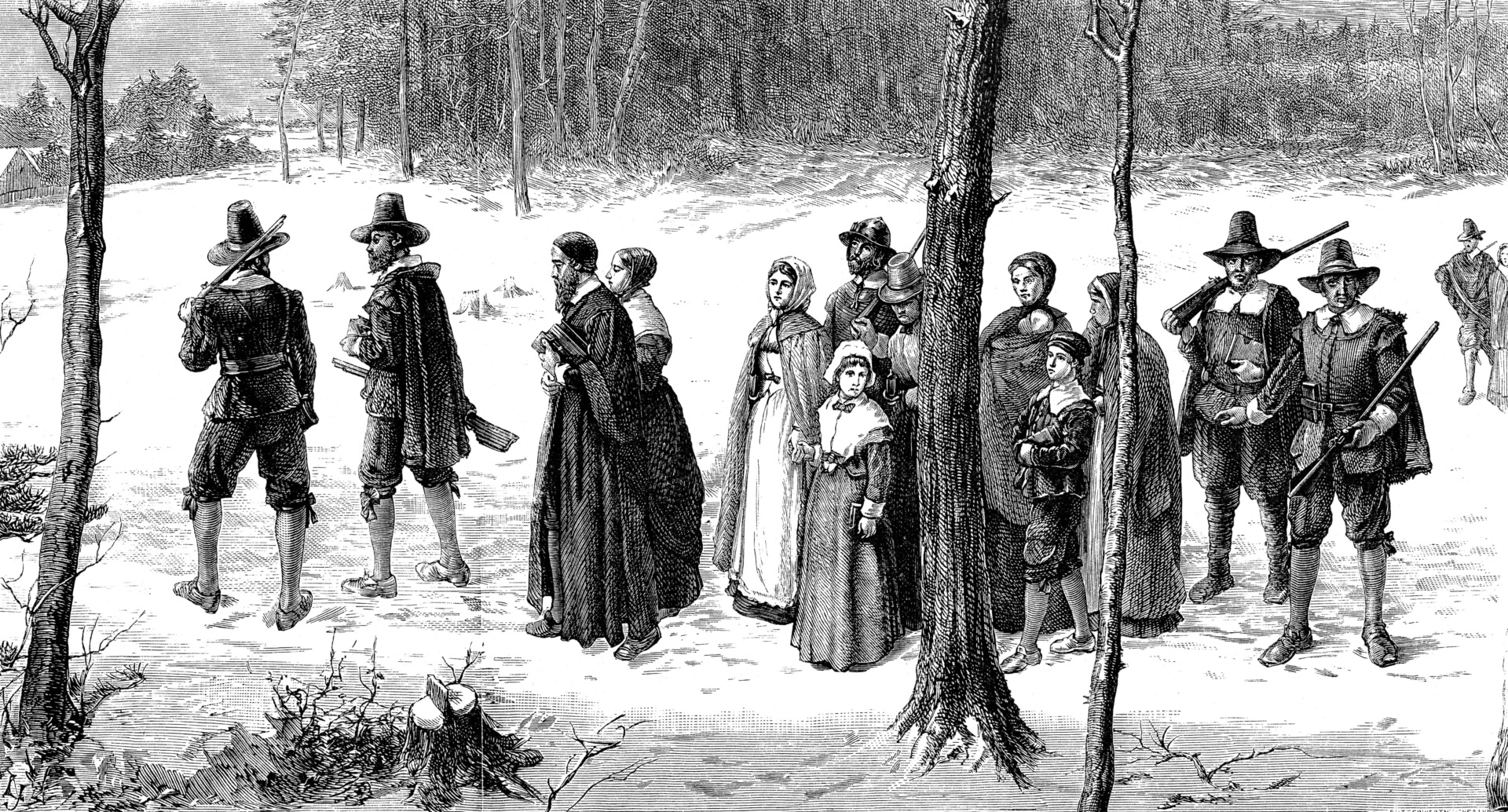

The Pilgrims on their way to church in the Plymouth Colony, 1620. Engraving of a painting by G.H. Boughton. (Photo by Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Making America Work

The enduring lesson of Plymouth isn’t just about property rights versus communalism, though that matters enormously. It’s about the link between ownership, production, and independence. The Pilgrims discovered that people work harder when they keep what they produce, but they also discovered that communities thrive when they actually produce things rather than simply consuming what others make.

Bradford’s 1623 reforms unleashed both individual initiative and collective capacity. Families farming their own plots meant more corn for everyone. A colony producing its own food and developing its own exports meant security and prosperity that no London merchant could guarantee or withhold.

When we gather for Thanksgiving this week, we’re celebrating a feast that nearly didn’t happen—a harvest made possible only after the Pilgrims abandoned the economic model their backers imposed and embraced the combination of private property and domestic production that would come to define the American project.

The Pilgrims made America great the first time by learning that liberty in the field leads to abundance on the table, and that real prosperity comes from making things here, not waiting for someone else to ship them.

It’s a lesson we’re learning all over again in the U.S. today.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.