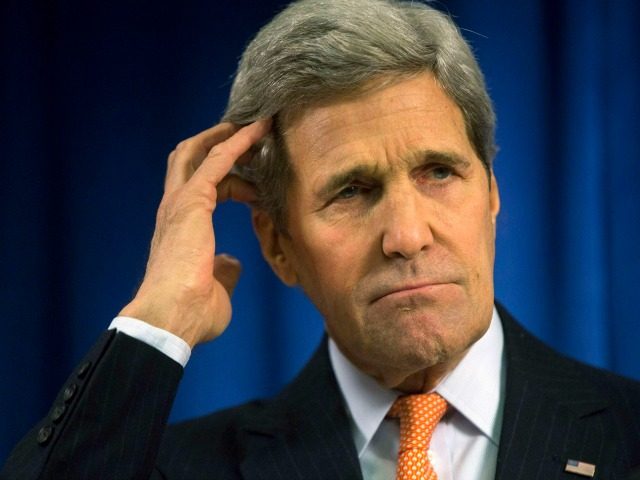

The Boston Globe reported on Friday that former Secretary of State John Kerry has been secretly working with Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif to save the Iran nuclear deal, which the Trump administration has strongly criticized and might renegotiate or cancel within the next two weeks.

The Boston Globe describes Kerry’s activities as “shadow diplomacy” and an “aggressive yet stealthy” effort to save “one of his most significant accomplishments”:

John Kerry’s bid to save one of his most significant accomplishments as secretary of state took him to New York on a Sunday afternoon two weeks ago, where, more than a year after he left office, he engaged in some unusual shadow diplomacy with a top-ranking Iranian official.

He sat down at the United Nations with Foreign Minister Javad Zarif to discuss ways of preserving the pact limiting Iran’s nuclear weapons program. It was the second time in about two months that the two had met to strategize over salvaging a deal they spent years negotiating during the Obama administration, according to a person briefed on the meetings.

With the Iran deal facing its gravest threat since it was signed in 2015, Kerry has been on an aggressive yet stealthy mission to preserve it, using his deep lists of contacts gleaned during his time as the top US diplomat to try to apply pressure on the Trump administration from the outside. President Trump, who has consistently criticized the pact and campaigned in 2016 on scuttling it, faces a May 12 deadline to decide whether to continue abiding by its terms.

Kerry also met last month with German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, and he’s been on the phone with top European Union official Federica Mogherini, according to the source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to reveal the private meetings. Kerry has also met with French President Emmanuel Macron in both Paris and New York, conversing over the details of sanctions and regional nuclear threats in both French and English.

Boston Globe Deputy Washington Bureau Chief Matt Viser sought to capture how both sides of the partisan divide are responding to the news of Kerry’s “unusual” activities:

As John Kerry seeks to save the Iran deal, supporters see unflagging energy even amid potential failure. Critics may see something else: a former officeholder working with foreign officials to potentially undermine policy aims of a current administration. https://t.co/rJgFbZtthd

— Matt Viser (@mviser) May 4, 2018

As Seth Mandel of the New York Post pointed out, the “supporters” half of Viser’s formulation is a matter of partisan opinion, while the “critics” half is a literal description of what Kerry is actually doing. One suspects mainstream media coverage of, say, Condoleeza Rice jetting around Europe to secretly undermine Barack Obama’s foreign policy in 2010 would not have praised her “unflagging energy.” The Obama administration veterans and sympathizers quoted in the Boston Globe piece sound an awful lot like people either ignoring the results of a presidential election or seeking to nullify it.

There is also the question of whether Kerry’s activities violate the Logan Act, that highly controversial and almost completely ignored piece of 18th-century regulation that expressly forbids private citizens from undermining U.S. foreign policy. The relevant U.S. Code reads as follows:

Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be, who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.

The Logan Act is something of a joke among legal scholars and political analysts, who often call for it to be repealed as obsolete rubbish because no one has ever been convicted under it… but it recently was employed as the pretext for action against President Trump’s first National Security Adviser, Gen. Mike Flynn.

Flynn was not actually charged under the Logan Act, but he pled guilty to making false statements during an investigation based upon it, as CNN explained in December 2017:

In court filings, Michael Flynn acknowledged he lied to the Federal Bureau of Investigation about calls with foreign officials, including the Russian ambassador, to try to influence the outcome of a UN resolution in December 2016 while a member of President-elect Donald Trump’s transition team.

Michael Zeldin, a former prosecutor who was a special assistant to Mueller in the Justice Department, said the outreach to foreign governments by Trump’s team at the time the Obama administration was in dispute with Israel over the vote is “facially” a violation of the Logan Act.

Flynn’s contact with the Russian ambassador “seems to violate what the Logan Act intended to prevent,” Zeldin said. He added that even though the Logan Act hasn’t been used successfully “it doesn’t mean that Mueller wouldn’t consider using it to pressure defendants.”

The New York Times reported in February 2017 that Obama advisers heard about Flynn’s conversations with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak and “grew suspicious that perhaps there had been a secret deal between the incoming team and Moscow, which could violate the rarely enforced, two-century-old Logan Act barring private citizens from negotiating with foreign powers in disputes with the United States.”

In December 2017, the NYT ran an op-ed from Daniel Hemel and Eric Posner that took the Logan Act very seriously indeed, and warned the Trump team they should “fear” it:

The statute, which has been on the books since the early days of the republic, reflects an important principle. The president is — as the Supreme Court has said time and again — “the sole organ of the nation in its external relations.” If private citizens could hold themselves out as representatives of the United States and work at cross-purposes with the president’s own diplomatic objectives, the president’s ability to conduct foreign relations would be severely hampered.

Hemel and Posner dismissed the argument that the Logan Act could be ignored because it has never been successfully prosecuted before, arguing that both Flynn and whoever directed his actions — they suggested President Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner — should be jailed, and even suggested impeachment proceedings for Trump and Vice President Mike Pence.

“If the phrase ‘high crimes or misdemeanors’ means anything, it includes violation of a serious criminal statute that bars citizens from undermining the foreign policy actions of the sitting president,” they declared.

As Dan McLaughlin points out at National Review at the end of an argument for repealing the Logan Act, Kerry has potentially set himself up for more serious charges under the law than Flynn, who was “apparently acting for a duly-elected incoming presidential administration” when he committed his alleged transgression. Kerry can make no such claim.

Chief political correspondent Byron York makes the same case that investigating Flynn under the Logan Act but giving Kerry a free pass is illogical:

Have often argued that 1799 Logan Act, used as pretext to question Michael Flynn, is dead. So IMHO it's dead for John Kerry, too. But if you believe Logan Act was used legitimately against Flynn, you've got to want a DOJ/FBI Kerry investigation…

— Byron York (@ByronYork) May 5, 2018

York noted in December 2017 that the Logan Act was the reason Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates, an Obama administration holdover, decided to interrogate Flynn:

Yates described the events in testimony before a Senate Judiciary Committee subcommittee on May 8, 2017. She told lawmakers that the Logan Act was the first concern she mentioned to McGahn.

“The first thing we did was to explain to Mr. McGahn that the underlying conduct that Gen. Flynn had engaged in was problematic in and of itself,” Yates said. That seems a clear reference to the Logan Act, although no one uttered the words “Logan Act” in the hearing at which Yates testified. “We took him [McGahn] through in a fair amount of detail of the underlying conduct, what Gen. Flynn had done.”

Yates and the aide returned to the White House the next day, Jan. 27, for another talk with McGahn. McGahn asked Yates “about the applicability of certain statutes, certain criminal statutes,” Yates testified. That led Sen. Chris Coons, who had called for an investigation of the Trump team for Logan Act violations months before, to ask Yates what the applicable statutes would be.

“If I identified the statute, then that would be insight into what the conduct was,” Yates answered. “And look, I’m not trying to be hyper-technical here. I’m trying to be really careful that I observe my responsibilities to protect classified information. And so I can’t identify the statute.”

While Yates became reticent in the witness chair, the public nevertheless knows from that “official familiar with her thinking” that Yates believed Flynn might have violated the Logan Act, a suspicion she shared with other Obama administration officials.

The coda to the Mike Flynn Logan Act saga is that a House Intelligence Committee report released on Friday made it clear that the FBI agents who interviewed Flynn “didn’t think he was lying.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.