Dem Rep. Smith on Stock Market: Fed Should Cut Rates, ‘Inflation Is Down Pretty Close to Zero’

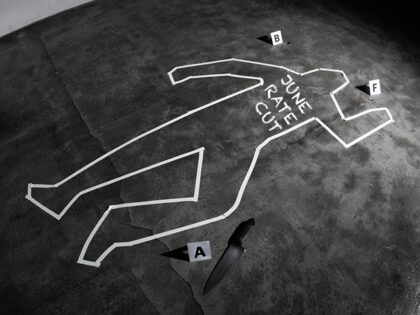

On Monday’s broadcast of “CNN News Central,” Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA) responded to the tumble in the stock market by stating that the Federal Reserve needs to cut interest rates and “inflation is down pretty close to zero. And now,