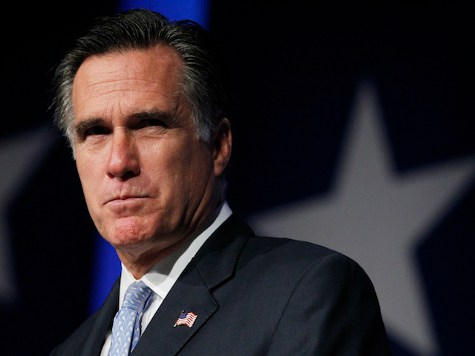

The subject of why Mitt Romney lost is so interesting that I will divide my analysis into two parts: first, on Romney the candidate, and second, on Romney the campaign CEO.

Sorry, Mitt, whether you want to admit it or not, it was your campaign. These were your people, many of them with you for a decade a more, and you stuck with them till the bitter end. You not only own them, you paid a pretty penny for them.

The purpose of this series is to provide one Democrat’s perspective on the contemporary Republican Party. As I wrote in the previous installment of this series, I believe that the Grand Old Party faces the distinct prospect of becoming a Grand Defunct Party. And since America as a whole benefits from a vigorous two-party system, such a fate for the Republicans should be avoided–although the Republicans themselves, of course, need to confront their own need for immediate reform and renewal.

Fortunately, one aspect of that reform and renewal is already under way: the complete disappearance of Mitt Romney from the political scene.

We can begin by saying that Romney is obviously an intelligent businessman, as well as a sterling family man. But this election was about the American family, not Romney’s.

Ask yourself this: Was there ever a moment in the campaign–that is, the long campaign, across two presidential elections, from 2007 to 2012–in which Romney ever showed a moment of spontaneous empathy? That is, seemed to genuinely care about other people, and the challenges they face?

Indeed, if we close our eyes and envision Romney, it’s easy to add a mustache and see that Romney has morphed into Tom Dewey, the Republican presidential nominee who lost twice to the Democrats, in 1944 and 1948. Dewey lost in Franklin D. Roosevelt in ’44; okay, nobody was going to beat FDR in the middle of World War Two.

But four years later, in 1948, Dewey lost to Harry Truman–that was an election that the GOP should have won. Indeed, in the ’46 Congressional midterms, the Republicans had won a huge victory, sort of the way that the Republicans won a huge victory in the ’10 Congressional midterms.

Yet Dewey and the GOP managed to fritter away their momentum going into the presidential election year. And when a leading wit of the day said that Dewey looked like the little man on top of the wedding cake, the mental image stuck. That’s who Dewey was–a stiff little prig, persuading and inspiring nobody.

So Truman won a surprise victory against a surprisingly weak challenger, just as Barack Obama did this year.

Indeed, it’s always been readily obvious that his talents as a political leader were always minimal. Indeed, his campaign was so lame that we have to even wonder how good a businessman he was–or effective a president he would have been.

For example, this year, the Obama campaign started ripping into Romney on Bain Capital in the spring. Start the carpet-bombing early: it’s an old and proven tactic for incumbents. Indeed, it’s exactly what another Democratic incumbent, Bill Clinton, did to Republican challenger Bob Dole back in 1996. Back then, Dole didn’t have the money to respond, and this year, the Romney campaign, too, claimed that it lacked the money.

The issue was that Romney had reached his spending limit for the primaries, and so he had no spendable campaign money to respond to Obama until Romney formally received the GOP nomination at the Tampa convention on August 28. That was a long time for Romney to be effectively mute in response to the incessant Obama attacks. Indeed, it’s fair to say that Obama cemented his lead during the spring and early summer–and Romney never really cracked that lead.

But Romney had another choice: He could legally have given himself the money for the primary season. As we all know, that was the huge difference between Dole and Romney–Romney had hundreds of millions of his own wealth. He could have put it into his campaign, or even lent it to his campaign–after all, he raised some $800 million for the general election cycle.

Indeed, four years earlier, Romney had donated more than $42 million to his 2008 campaign. And yet this time around, he put in nearly nothing. That was a fatal mistake for Romney, a fatal shortchanging of himself.

Romney has a right to do whatever he wants with his money, of course, but if he was going to invest five years of his life into seeking the White House, one might think that he would have wanted his money to work as hard as he, himself, was working.

So why didn’t Romney pony up? What was the problem? We don’t yet know; maybe we never will know.

All we do know is that even as Romney was shortchanging his own campaign, he was spectacularly failing to eliminate a gaping vulnerability–the issue of his own taxes. There’s no point in overly rehashing the Grand Cayman Islands business one more time here.

Suffice it to say, the revelations about Romney’s overseas bank accounts, and the low tax rate he paid as a result, were ruinous to his campaign. Note to future moguls who might be eyeing the White House: If want to lead this country, you have to show some solidarity with the people, and that means paying a fair share of taxes.

Romney might have obeyed the law, yadda yadda, but he needed to obey the spirit of the law. He needed to show that he understood the American ethos of fairness and shared sacrifice. Somewhere over the last decade, Romney should have revised his assets so that he was paying a larger share in federal income tax; it would have been costly for him, to be sure, but if he had done so, he might now be on his way to the White House.

So if we think about Romney’s thrift on his ’12 campaign, and his unwillingness to reorganize his wealth to deprive his critics of a criticism, we have to wonder: Did Romney really want to win? Or was he so arrogant that he thought he could do it all his way, heedless of the realities confronted by lesser men?

Yet in one area, not concerning money, Romney was willing to do anything to win. As everyone knows, Romney’s political career meandered from moderate to conservative, then back to moderate again. It can certainly be argued that in politics, flexibility is a virtue, or at least a necessity. Yet Romney was uniquely mechanical and soulless in his paint-by-numbers attempt to portray himself as the most optimally vote-maximizing candidate he thought he should be at any given moment.

So Romney was cheap on his own tangible wealth, but promiscuous on an intangible kind of wealth–his reputation for consistency and, yes, honesty.

Indeed, Romney’s endless mutability gave rise to a sort of Beltway parlor game: Who is the real Mitt, and what would he actually do if he were to win? We’ll never know now, of course, but it’s easy to believe that the real Romney is a socially conservative Mormon, as his own personal life story attests.

Yet it’s also easy to believe that the real Romney is a situational deal-maker, as his business career attests. One or both of those traits might have been acceptable, but it became apparent that even Romney didn’t know his own true self–so how could he be persuasive to voters?

For example, he could call himself “severely conservative” on the primary campaign trail earlier this year, and then, in the third and final presidential debate on October 23, act as if he was applying to be Obama’s team-playing national security adviser. So what happened? Did someone pull out the campaign’s Etch-A-Sketch?

I wrote the very next day for Breitbart News that Romney was “too forbearing” to Obama in that third debate. And I laid out the scenario for what Romney should have said, repeating go-on-the-foreign-policy-offensive themes that I had been writing about for weeks:

Four days later, writing for Breitbart on October 28, I lamented, “Unfortunately, Romney himself let the Libya issue drop in his third and last debate.” And that was his last chance. Evidently Romney believed his campaign staffers when they told him that he was going to win if he just played it safe in that last debate–and no motives of heartfelt principle inspired Romney to reject that advice and speak out on important national security issues.

As I have said, foreign policy is not the number one issue, but in a close race, it can still be the tipping point. And there are some issues–such as the threat of a nuclear Iran–that unite almost all Americans. So it couldn’t have hurt Romney to speak more forcefully to those widespread national security concerns.

Instead, Romney chose to speak forcefully on other issues, notably his true feelings about many of his fellow Americans–the 47%. Apparently he really does believe that he and his rich friends are overlording “masters of the universe,” engaged in a rich-man’s class warfare against the bottom half of the population.

The “47 percent” of the population that Romney derided as hopelessly dependent included, of course, retirees and war veterans–many of whom voted for him anyway. But of course, many didn’t.

Indeed, a look at the 2012 exit poll shows that Romney lost the election because of his seemingly uncaring attitude. In the exit poll, voters were asked which of four key traits in the presidential candidate were most decisive in determining their vote. The four choices were, “shares my values,” “is a strong leader,” “has a vision for the future,” and “cares about people like me.”

Romney won the votes of those in each of the first three choices, but among the 21% of Americans who said that the trait most affecting their vote was “cares about people like me,” Obama won, 81% to 18%. If one does the math, that means that Obama’s net vote-advantage for this segment of the electorate was 13 points. In other words, “cares about people like me” won the election for Obama–and lost it for Romney.

Was this a bad rap on Romney? A media hit job? Evidently not. The final proof that Romney really does see the world in such insular and repugnant country-club terms came after the election, when he repeated the same basic formulation by arguing that Obama had won the election by giving “gifts” of federal programs to various constituencies.

To be sure, there’s more than a little truth to the argument that politicians deliver favors to favored groups, but Romney should nevertheless possess the self-awareness to know that he, too, has been the beneficiary of federal “gifts.” Specifically, the “carried interest” provisions of the tax code–which enabled him to pay a lower income tax rate than tens of millions of Americans with one-thousandth of his net worth–is as big a federal gift as exists in America today.

Note to Republicans: If you ever think about nominating a candidate who takes tax deductions on his dressage horse and then complains about other people getting free money, you should think again.

Nor was Romney alone in his blundering ways. Plenty of Republicans helped the Party lose an election that it should have won. Not only did they help it lose, but those Republicans got rich–filthy rich–helping the GOP lose.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.