Now that the Senate has passed the deeply flawed “Gang of 8” immigration bill with fewer than the 70 votes that proponents originally boasted, the spotlight has shifted to House Republicans. Early indications are that House Judiciary Committee Chair Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-VA) intends to introduce reforms piece-by-piece, rather than adopting the Senate’s “comprehensive” approach, which produced an unwieldy, unworkable bill that traded legal status for current unlawful aliens for lackluster, ineffectual promises on border security.

Democrats will undoubtedly resist being made to face up-or-down votes on individual proposals, and some Republicans, too, will push House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) to put together a comprehensive package. They will point out that bills require both houses to work together, and that the Senate is unlikely to accept a piecemeal process after it has kicked off the legislative process. As House Republicans deal with that pressure, they ought to consider the example of the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily staved off civil war.

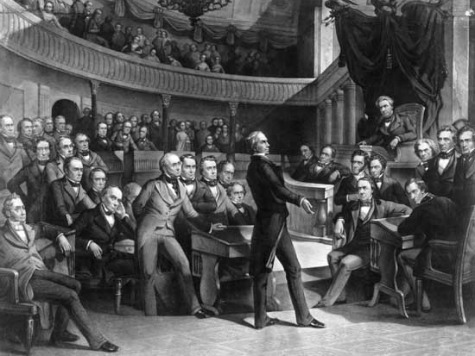

The Compromise of 1850 was a law passed against the backdrop of growing confrontation between North and South over the issue of slavery–in particular, whether slavery would be allowed in new territories in the west. It consisted of five separate proposals, which Senator Henry Clay–the Great Compromiser himself–tried to pass in a single omnibus bill. Senator Daniel Webster, an abolitionist and by then a Washington institution, threw his support to Clay’s comprehensive package. But the giant bill failed to pass, and tensions grew.

Finally, Senator Stephen Douglas–a consummate back-room dealer, and Abraham Lincoln’s future opponent–offered a different approach: each portion of the bill would be offered up for a separate vote. Over several weeks, each of the five proposals was debated–and each was passed, satisfying all sides and relieving the parties from the internal conflicts that would eventually split the Democrats and destroy the Whigs. Passing each part separately built trust–and allowed for more deal-making, giving more legislators a stake in the deal.

The United States is not facing civil war today, but is struggling to deal with ideological divisions that have been sharpened during the Obama presidency. In the wake of Obama’s re-election, largely on the strength of support from minority voters, Republicans are divided as to how to meet the challenge. Some advocate a return to conservative principles, while others–the “establishment”–favor selective compromises aimed at reversing Republican losses among minorities, particularly the fast-growing Hispanic electorate.

Though the Senate bill was co-sponsored by Republicans in the “Gang of Eight,” and included key amendments by other Republicans aimed at satisfying concerns about border security, the majority of Republicans voted against the bill. House Republican leaders quickly became aware that if they were to push the Senate bill through their caucus, or to bring it to a vote without the support of a majority of the caucus, it could lead to open revolt and damage the party–not just in Washington, but across the nation, and perhaps permanently.

That is partly why they have committed, publicly, to a piece-by-piece process. Subjecting immigration reform to a piecemeal approach gives conservative Republicans increased leverage over each separate bill, as well as over the sequencing of bills, which will undoubtedly place border security ahead of proposals for a so-called “path to citizenship” for illegal aliens currently in the country. But a piecemeal approach also favors Boehner’s political skills, which are sharpest behind the scenes, and could result in strong Republican support in the end.

No immigration reform, whether one bill or several smaller bills, will completely solve the problems that have led to the current national confrontations over spending, culture, and the role of government in our society. It is possible that a deal on immigration reform would only postpone the intense partisan contests that lie ahead in the remainder of Obama’s term and the era to follow. But a Compromise of 1850-style piecemeal approach might preserve the Republican Party to fight another day. Otherwise, no deal may be better than a bad deal.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.