A consortium of international journalists began reporting this weekend on the contents of a massive data leak from Credit Suisse that exposed 18,000 formerly secret bank accounts valued at over $100 billion in total.

The reports describe huge amounts of money stashed in the Swiss bank by strongmen and shady characters, including officials accused of human rights abuses and subjected to punitive sanctions.

The data was initially given to a left-wing German newspaper called Suddeutsche Zeitung by a self-described “whistleblower.” The German paper gave the pilfered data trove to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which in turn passed it along to about 50 newspapers around the world for analysis and reporting.

A similar strategy was employed with the “Panama Papers” leak of data from the Mossack Fonseca law firm in 2016, which exposed how the now-defunct Panamanian law firm helped unsavory characters move their money around the world, and the “Pandora Papers” leak in 2021, which exposed wealthy and powerful individuals making secretive purchases of expensive luxury goods. The Panama Papers were also given to Suddeutsche Zeitung first by their leakers.

In the case of the Credit Suisse leak, none of the information provided by the whistleblower concerned the bank’s current operations. The oldest records included in the leak dated back to the 1940s, while the most recent were from the early 2010s.

OCCRP dubbed Credit Suisse the “Bank of Spies” because many of the high-value secretive accounts exposed in the leak were owned by high-level intelligence officers or their family members, including spymasters from Jordan, Yemen, Iraq, Egypt, and Pakistan. (The media consortium working with OCCRP evidently wants to christen the story “Suisse Secrets,” although it’s not clear if the sobriquet will catch on).

OCCRP exposed 15 intelligence officials in total while choosing not to reveal the names of others because “their identities could not be verified beyond absolute doubt.”

The watchdog group highlighted four individuals in particular: the late Sa’ad Khair of Jordan, Omar Suleiman of Egypt, Gen. Akhtar Abdur Rahman of Pakistan, and Ghaleb al-Qamish of Yemen.

The report strongly implied these officials looted their black-ops budgets and salted millions of dollars away in Swiss bank accounts with the usual accountability rules bent or discarded completely because they were helpful to the United States during the War on Terror:

All four ran state intelligence agencies where they controlled large black budgets that were above parliamentary and executive scrutiny. All of these figures or their family members also held personal accounts at Credit Suisse worth large sums of money, without obvious sources of personal income that could explain the wealth.

All four had roles in key U.S. interventions in the Middle East and Afghanistan, from the CIA’s early attempts to back anti-Soviet mujahideen in the late 1970s, to the first Gulf War in 1990, to the so-called “forever wars” launched in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2001.

Detainees stand together at a fence at Camp Delta prison at the Guantanamo Bay U.S. Naval Base, Cuba. (AP Photo/Brennan Linsley)

“In the example of an intelligence chief like Sa’ad Khair, opening an account is a red flag and many banks in Switzerland would not take it, but Credit Suisse would,” a former Credit Suisse executive told OCCRP.

The report suggested Akhtar got rich by skimming from the large amounts of money the U.S. funneled to Afghan jihadis when they were fighting against Soviet occupation.

Qamish, the Yemeni spy boss, worked for deposed Yemen strongman Ali Abdullah Saleh, forced out during the “Arab Spring” turmoil of 2011, threw his support behind the Iran-backed Houthi terrorist insurgency during the brutal Yemeni civil war, and was liquidated by his Houthi partners when he announced he was willing to make peace with Saudi Arabia.

Qamish made out much better than his old boss, building up a tidy $4 million in his Credit Suisse account before withdrawing his money and settling down to a comfortable retirement in Istanbul after the Arab Spring reshuffled Yemen’s government. OCCRP suggested some of Qamish’s fortune was drawn from funding provided by the CIA for terrorist “rendition” programs, which the watchdog group despises as human rights violations.

Egypt’s Suleiman likewise racked up $80 million in his Credit Suisse accounts while working for longtime pro-U.S. strongman Hosni Mubarak, who lost power during the Arab Spring. A former CIA agent named Robert Baer told OCCRP that Mubarak indulged, and even encouraged, graft among his top military and intelligence officials because he felt they were less likely to stage a coup against him if they were getting rich in his service.

OCCRP charged that some $8 billion in Credit Suisse accounts belonged to customers who should not have been allowed to do business with the bank at all, including such ugly customers as Venezuelan socialist elites who were obviously looting their country’s national wealth while its economy collapsed.

Nnon-governmental organizations and the Catholic Church have held food aid days to help people and children living on the streets or in extreme poverty in Caracas, Venezuela on 30 November 2017. (Photo by Roman Camacho/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

“I’ve too often seen criminals and corrupt politicians who can afford to keep on doing business as usual, no matter what the circumstances, because they have the certainty that their ill-gotten gains will be kept safe. Our investigation exposes how these people can bypass regulation despite their crimes, to the detriment of democracies and people all over the world,” OCCRP co-founder Paul Radu said in a statement accompanying the release of the Credit Suisse data.

The statement also quoted the unidentified whistleblower, who rejected Credit Suisse’s defense that the old records contained in the leak are “predominantly historical” and early reports on the leak are “based on partial, inaccurate, or selective information taken out of context.”

“The pretext of protecting financial privacy is merely a fig leaf covering the shameful role of Swiss banks as collaborators of tax evaders. This situation enables corruption and starves developing countries of much-needed tax revenue,” the whistleblower declared.

CNBC noted on Sunday that some of the account holders identified in the leak were under international sanctions, such as a Zimbabean businessman linked to former dictator Robert Mugabe.

The New York Times (NYT) cited the leak as the latest proof that Switzerland’s “prohibitions on taking money linked to criminal activity” are loosely enforced.

“With its ironclad bank-secrecy laws, Switzerland has long been a haven for people who are looking to hide money. In the past decade, that has made the country’s largest banks – especially its two giants, Credit Suisse and UBS – a target for the authorities in the United States and elsewhere who are trying to crack down on tax evasion, money laundering and other crimes,” the NYT wrote.

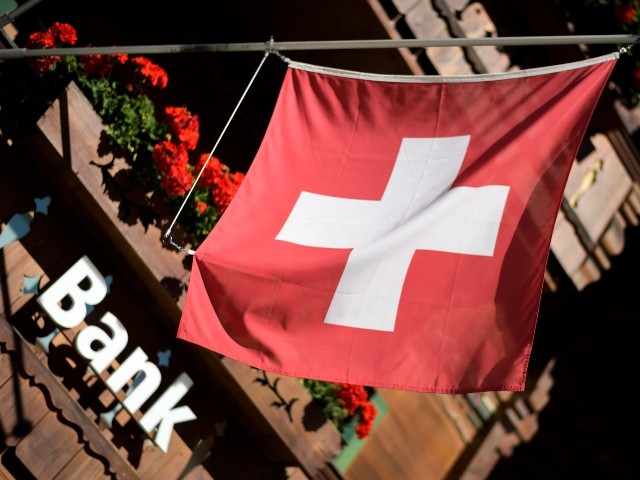

A sign “Bank” is seen beneath a Swiss flag on the front of a local banking branch on August 22, 2017, in Gstaad. (Photo by FABRICE COFFRINI/AFP via Getty Images)

Another NYT piece on the leak quoted Nadim Houry of the Arab Reform Initiative denouncing a “very sophisticated, corrupt elite that is very integrated into the global financial system.” He criticized banks like Credit Suisse for helping elite politicians seize national wealth and “act like absolute monarchs disposing of personal property.”

In its response to the leak, Credit Suisse argued the OCCRP and its journalistic partners were attempting to manufacture scandals by using a modern legal framework to analyze decades-old data from “a time where laws, practices, and expectations of financial institutions were very different from where they are now.”

The bank noted the vast majority of the accounts criticized by OCCRP have long since been closed, and in many cases the former account holders are deceased. Credit Suisse spokeswoman Candice Sun dismissed the OCCRP reports, and the flood of accompanying major media reports, as “a concerted effort to discredit the bank and the Swiss financial marketplace, which has undergone significant changes over the last several years.”

The NYT acknowledged these realities and said they reduced “chances that the revelations will inspire accountability efforts,” but quoted Houry and others insisting the problems with international banking remain as bad as ever, especially in the famously corrupt Middle East.

Houry asserted oversight reforms and anti-corruption laws imposed after the Arab Spring were mostly “window dressing” because “the power dynamics have not changed and no state controller is able to hold the powerful to account.”

Tunisian protesters carry flares and shout slogans during celebrations in central Tunis on January 14, 2018, marking the seventh anniversary since the uprising that ousted ex-president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali and launched the Arab Spring. (ANIS MILI/AFP via Getty Images)

As with the Panama and Pandora Papers, many of the individuals scandalized by reporters in their “Suisse Secrets” coverage insist they broke no laws, although the amount of money some political leaders have been keeping in secretive Swiss accounts is hard to justify when their national economies are spiraling into ruin.

The UK Guardian, for example, made much of Jordanian King Abdullah’s six bulging Credit Suisse accounts (plus one for his wife) while Jordan has experienced “a struggling economy, persistent levels of poverty, high unemployment, cuts to welfare and seemingly ever-present austerity measures” over the past decade.

“Lawyers for King Abdullah and Queen Rania said there had been no wrongdoing by the clients, and gave an account of the source of their funds, which they said were compliant with applicable tax law,” the Guardian noted, while insisting that “details of more offshore accounts will add to allegations that Jordan’s king of 22 years lives a life disconnected from the demanding realities faced by most of its citizens.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.