Dmitry Rogozin, head of Russia’s Roscosmos space agency, claimed on Tuesday that Venus is a “Russian planet” because “our country was the first and only one to successfully land” there.

Venus suddenly became a more desirable tourist destination this week with the announcement that possible signs of microbial life have been detected in the atmosphere.

Rogozin said the Russian spacecraft sent to Venus “gathered information about the planet,” revealing that “it is like hell over there.” Most astronomers would say they already suspected as much.

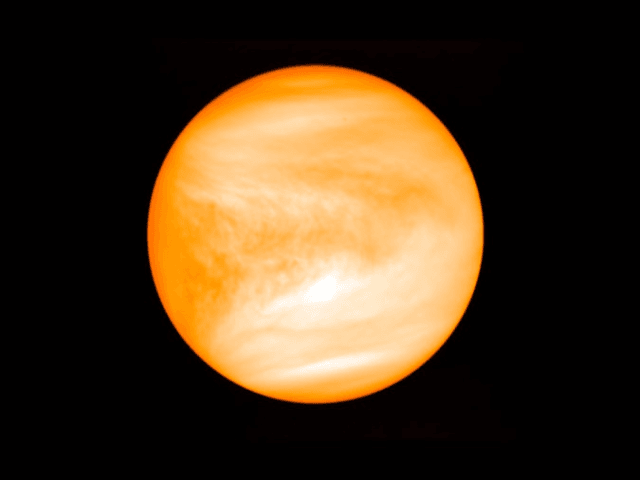

Venus shares little in common with Russia. The average surface temperature is about 900 degrees Fahrenheit, which is about 845 degrees warmer than the current temperature in Moscow. The atmosphere on Venus rotates faster than the planet does, so visitors can expect landings even bumpier than Siberia. The air in some Russian cities can be a little hard to breathe at times, but the Venusian atmosphere is 100 times denser on a good day, and it is more toxic than the tea served aboard certain Russian airliners.

Rogozin’s claim of Russian kinship with Venus rests on the mission of Venera 7, a Soviet probe that managed to land on the Venusian surface in 1970, eight years after the U.S. Mariner 2 spacecraft made the first close flyby of the planet. The Soviets obtained the first images of the surface with the Venera 9 probe in 1975, and the first color photos in 1982 with Venera 13, which was impressively able to endure the Solar System’s most formidable sauna for over two hours.

Venus is suddenly a hot property because an international astronomy team announced on Monday that traces of phosphine gas have been discovered among the clouds of the hothouse planet. Microscopic life living in liquid droplets might be one explanation for the gas.

No other current theory of the Venusian atmospheric system accounts for the presence of rare phosphine gas in quantities thousands of times greater than volcanic eruptions, electrical storms, or other common chemical reactions could explain. On Earth, phosphine gas is generally either an industrial byproduct or a sign of microscopic organisms that can survive without oxygen.

“In order to make this quite extraordinary claim that there might be life there, we really have to rule everything out, and that’s why we’re very cautious saying we’re not claiming there’s life, but claiming there’s something that is really unknown and it might be life,” team member William Bains of MIT cautioned when announcing the findings.

The most optimistic theory of life on Venus holds that the surface was colder and wetter in ancient times, possibly leading to the development of microbes that migrated into the cooler reaches of the upper atmosphere. At altitudes of about 50 kilometers, conditions in the Venusian atmosphere reach heat and pressure that would not instantly kill Earthlings, provided they enjoy breathing sulfuric acid – and there are microorganisms that might, or that may have found habitats in droplets of less toxic liquid high in the clouds.

Rogozin seemed dubious about the possibility of life in the Venusian clouds, based on his comments on Tuesday, but he said Russia plans to launch another mission to Venus “without involving wide international cooperation” in addition to the next Venera-series probe, the Venera-D, which is supposed to be conducted in cooperation with the United States, possibly in five or six years.

In addition to the space probe efforts, Russian billionaire Yuri Milner quickly announced funding for a new project to study the possibility of life on Venus headed by MIT scientist Sara Seager, who was involved in the phosphine gas discovery.

“Finding life anywhere beyond Earth would be truly momentous. And if there’s a non-negligible chance that it’s right next door on Venus, exploring that possibility is an urgent priority for our civilization,” Milner said on Tuesday.

“We are thrilled to push the envelope to try to understand what kind of life could exist in the very harsh Venusian atmosphere and what further evidence for life a mission to Venus could search for,” Seager added.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine also wanted to “prioritize Venus” after the discovery of phosphine, which he described on Monday as “the most significant development yet in building the case for life off Earth.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.