Let’s consider some of the lessons that we’ve learned, these past three years, about Big Tech.

In 2016, we discovered that Big Tech was vulnerable — wide open, in fact — to political manipulators and hackers, both domestic and foreign. In 2017, we learned that Big Tech didn’t want to do much about the problem, even though the techsters did wish to pursue their various lefty political agendas. And in 2018, we learned that Big Tech was finally willing to do something about its vulnerabilities — but only on its terms.

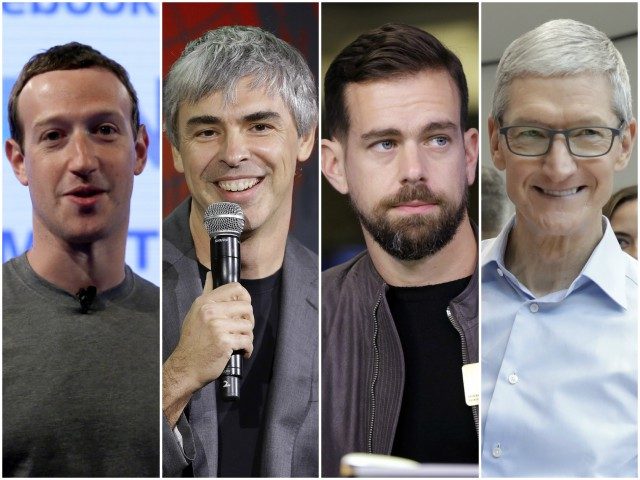

By “Big Tech,” we mean, of course, the giant Silicon Valley-based companies, notably Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Apple. We might pause to observe that those first three firms are typically known as “social media” companies, while Apple is best known for hardware. And yet Apple is increasingly a software company, too, and virtually all software these days has a social-media component — and also, of course, various political dimensions.

In the meantime, plenty of other tech companies not in Silicon Valley also deserve inclusion in “Big Tech.” For instance, there’s Seattle-based Amazon and Microsoft (Microsoft, for example, now owns LinkedIn). And at the southern end of the West Coast, let’s not forget such Los Angeles-based outfits as Snapchat and Blizzard Entertainment, a leading maker of video games. Wherever they are geographically, Big Tech companies share the same avid enthusiasm for social-media-generated big data. Which is to say, they want to know all about you, including your political preferences.

So we must ask: What’s been the effect of Big Tech on our politics?

In 2016, Google’s Gmail was penetrated by Wikileaks, and the resulting revelations from the account of John Podesta convulsed the Hillary Clinton presidential campaign, perhaps affecting the outcome of the election. In the same year, Facebook later conceded, that company’s advertising system was influenced by the Russians.

To be sure, many mysteries about 2016 still remain. For instance, some say that the Google-slayers of Wikileaks are just a front group for the Russians—although Wikileaks’ Julian Assange stoutly denies it. And as for the Facebook manipulators, one need not conclude that Donald Trump knew anything about what the Russians were doing online to conclude, nonetheless, that the Russians were doing something.

Indeed, just on Monday, Rep. Mike Conaway (R-TX), chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, issued his final report on the whole matter; the document concluded that there was no case against the Trump campaign, or even that the Russians were specifically trying to help Trump, as opposed to Moscow’s desire to generally mess with America. Yet still, Conaway hardly let the Russians off the hook: “The bottom line: The Russians did commit active measures against our election in ’16, and we think they will do that in the future.”

Yet whatever happened in 2016, a bit of perspective is useful. For instance, Facebook has estimated that the Russians spent a mere $150,000 on digital ads in 2016. That sum is not quite nothing, but is still chump-change compared to the combined $81 million on digital ads bought by the Clinton and Trump campaigns. (And anyone is free to guess whether or not other foreigners might have bought an ad or two, or done something else on social media to influence the election.)

In addition, we can observe that the official campaign-finance tallies — Clinton spent more than $1.1 billion, Trump about half that much — probably don’t fully show the plenitude of “money in politics.” For example, they don’t include the value of other kinds of “contributions” to the candidates. How, for example, does one put a price tag on the value of the Main Stream Media’s affection for Hillary and its disaffection for Trump? In October 2016, the Media Research Center concluded that 91 percent of the broadcast news coverage of Trump was negative. In political terms, such bias is also not nothing.

So now let’s turn to 2017, as Trump took office and #Resistance took to the streets. As we recall, Big Tech spent most of last year denying that anything bad had happened — at least not because of them. Indeed, the techsters were mostly happy to keep pushing their familiar progressive policies, including open borders for America.

Moreover, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg boasted of an even bolder vision. Last February 16, he published a 5700-word manifesto, grandly entitled “Building Global Community,” in which the tech titan declared, “Progress now requires humanity coming together not just as cities or nations, but also as a global community.” And he added cheerily, “Facebook can help.”

In fact, Zuckerberg soon was touring the United States, campaign style. Such carefully choreographed and photo-oped stumping led many to wonder if he was thinking about running for political office himself — maybe even for the presidency in 2020. If so, the timing wasn’t so good; bad publicity about Facebook soon brought Zuckerberg’s hopes, such as they might have been, crashing down.

Indeed, late in 2017, Facebook and other tech companies were hauled to Capitol Hill to testify before the U.S. Senate about what had happened in the past election — and what might happen in the elections to come.

Now thoroughly on the defensive, Facebook pledged to hire another 10,000 safety and security personnel — mostly content screeners — by the end of 2018. Of course, in light of Facebook’s long history of stifling conservatives, the immediate question arose from the right: Who would these people be? What would be their guidelines and protocols in evaluating content? To put it mildly, conservative concerns about Facebook’s bias have yet to be resolved.

So on January 4, 2018, when Zuckerberg offered his latest batch of deep thoughts, his tone was markedly different from the year before:

The world feels anxious and divided, and Facebook has a lot of work to do — whether it’s protecting our community from abuse and hate, defending against interference by nation states, or making sure that time spent on Facebook is time well spent. [emphasis added]

Indeed, by 2018, the criticism of Big Tech, especially Facebook, was free-flowing. We might consider, for instance, the words of Roger McNamee, a prominent Silicon Valley venture capitalist — and an early investor in Facebook — who published an article in a liberal DC publication, “How to Fix Facebook—Before It Fixes Us.” McNamee provided a long list of possible fixes, none of which the company will like, including anti-trust litigation aimed at breaking it up. Ouch!

In the meantime, criticism of Facebook has been coming from across the spectrum.

From the populist right, Breitbart News has bannered sharp headlines alleging bias, including, “Trump’s Facebook Engagement Declined By 45 Percent Following Algorithm Change,” and “Facebook Algorithm Change Hits Fox, Breitbart, Conservative Sites – CNN, New York Times Unaffected.”

To be sure, Facebook is hardly alone in getting hammered on the anvil of right-wing ire. Google, for instance, has been accused of firing employee James Damore purely for his un-PC views. And in January, Twitter was hit by James O’Keefe’s Project Veritas, which released hidden-camera videos that appeared to show the company’s engineers bragging about their ability to use algorithms to restrict conservative speech. More recently, Breitbart News headlined, “Twitter Does Nothing as Pamela Geller’s Daughters Are Harassed Off Platform.” Meanwhile, supporters of vigorous law enforcement still wonder why Apple has been more willing to cooperate with Chinese authorities than with American authorities.

And yet Facebook is still the biggest target. Indeed, the hits are now coming from the left, too; the emerging progressive narrative is that Hillary Clinton lost because of social-media skullduggery. Interestingly, even former President Barack Obama — who probably has benefited more than any politician alive from Big Tech love — said last month that America needed to have a “significant conversation” about possible regulation of the industry.

In the meantime, for everyone, the “ick” factor in response to tech intrusion is increasing. On March 7, The Wall Street Journal headlined, “Facebook Really Is Spying on You, Just Not Through Your Phone’s Mic.” As the Journal reporter said of Facebook’s denials of sneaky listening, “I believe them, but for another reason: Facebook is now so good at watching what we do online — and even offline, wandering around the physical world — it doesn’t need to hear us.” That is, Facebook doesn’t need to listen in on you through your mic, because it monitors you in every other way — through credit cards, GPS, WiFi usage, and, of course, apps.

In addition, we can learn a lot from a February 23 article in Wired, “How Trump Conquered Facebook—Without Russian Ads.” In that piece, Antonio Garcia Martinez, a Facebook advertising executive-turned-critic, stated, “It’s still not clear how much influence the IRA [the St. Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency] had with its Facebook ads.” And yet what is clear, Martinez continued, is that Facebook has a fantastically complicated system for pricing advertising — a system that seemed to favor Trump in 2016, giving him an enormous price-advantage over Clinton.

Is such a system fair? To be frank, it seems more infernal — as in, infernally incomprehensible — than fair or unfair. And if such a Rube Goldberg-ian mechanism happened to help Trump in 2016, well, that’s easy enough for the brainiacs at Facebook to fix – all it takes is a slight flick of the algorithm.

In other words, if Facebook feels pressure from the Democrats and the MSM — and it does, big time — it wouldn’t be hard for it to make changes to hurt, not help, Republicans in the next election. And oh, did Virgil mention that, irrespective of Martinez’s article, online click fraud is rampant?

So here’s where we seem to be with Big Tech in 2018: The country is ever more alarmed by what’s happening, and so the public’s desire to see tech regulated and restrained has surged. Yet, at the same time, few Americans have any understanding of what it would actually take to regulate Big Tech. But that’s not an argument against needed regulation; it’s just an observation that, as a country, we have a steep learning curve.

Of course, the regulation of new technology is always tricky. Once upon a time, the railroads were new and mysterious, and so was the telephone, and so was the airplane. And yet we figured it out.

In fact, the one great verity of regulation is more ancient than any of those technologies. And it comes from the Roman poet Juvenal, who two thousand years ago wrote the famous line, Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? That is, Who will guard the guardians?

The enduring lesson to take away from Juvenal is that nobody is to be trusted with exclusive power. That is, there should be checks and balances for everyone in authority, public or private.

Over the past couple of decades, we’ve had an experiment in self-regulation — that is, Big Tech acting as its own guardian, deciding what’s good for us. That hasn’t worked out so well; so now must come a set of new guardians, to watch over the old guardians — who weren’t guarding anything except themselves. And if these new guardians aren’t to be trusted, either? Well, then, we’ll have to keep adding layers of watchmen until we get it right.

Maybe that sounds like a big bureaucratic mess. But because Big Tech is so important, and because it’s not going anywhere, the reality is that there is no alternative to more guardianship.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.