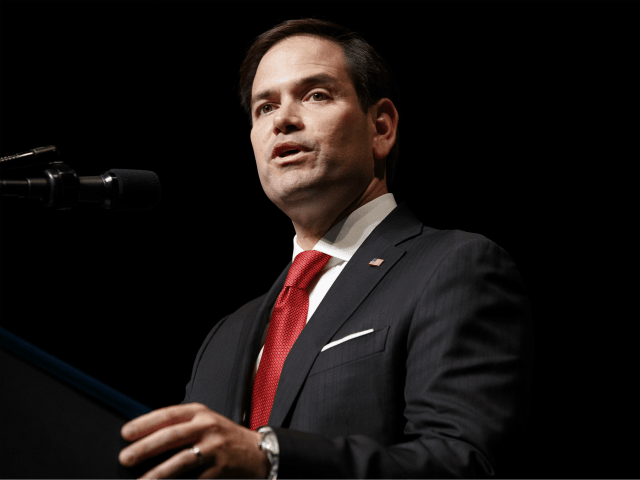

Sen. Marco Rubio’s idea of “common-good capitalism” makes obvious good sense, and yet, of course, not everyone agrees. Still, Rubio has started a valuable debate, and if he prevails, the Republican Party—and the United States—will be stronger.

In a speech to the Catholic University of America on November 5, Rubio made his case:

What we need to do is restore common-good capitalism–a system of free enterprise in which workers fulfill their obligation to work and enjoy the benefits of their work, and where businesses enjoy their right to make a profit and reinvest enough of those profits to create dignified work for Americans.

Does any of that sound politically risky? Or economically dangerous? In fact, it’s about as apple-pie as one can get.

And yet over at National Review, Kevin Williamson chose to drop an “f-bomb,” fascism. The Florida senator’s words are “the familiar moral basis of fascist economic thinking,” Williamson snapped. We can observe that such commentary says nothing about Rubio—and everything about Williamson.

In the meantime, Rubio has kept going. In another speech, this one to the National Defense University on December 10, he used the phrase “common-good capitalism” again, mostly in the context of strengthening our strategic security against China.

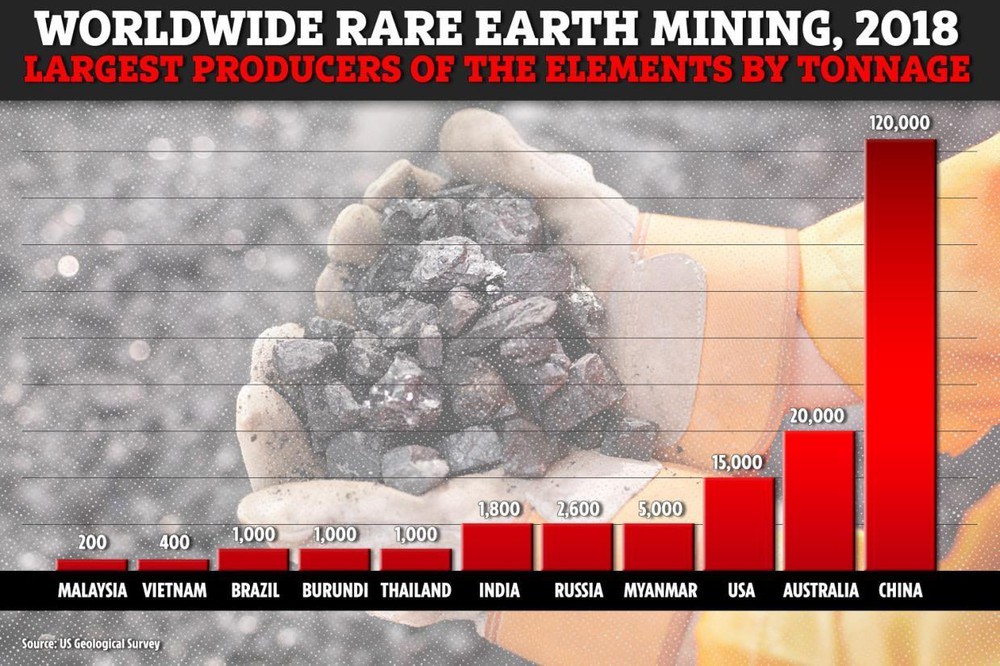

In particular, Rubio—who has long staked a strong position on China—argued that the dictates of free-market dogma can sometimes get in the way of national defense. Most obviously, we can’t have free trade with an opposing country; we didn’t, after all, keep trading with Nazi Germany during World War Two. And so today, Rubio declared, it’s particularly foolish to rely on China for the rare earth elements that we need for our tools and weapons. Thus he applauded the Trump administration’s efforts to reopen rare-earth mines that had been closed during the Obama administration; the goal, of course, is always to have a reliable domestic supply on hand.

Then Rubio went even further, arguing that it should be our stated policy that a strong national defense means good jobs, at good wages, on the homefront. This is an idea with deep roots in American security thinking; it was Franklin D. Roosevelt, our commander-in-chief during World War Two, who declared in 1940 that American workers would build the “arsenal of democracy”; that is, we must be the leading nation making the wares of war, providing jobs for workers and strength for our warriors.

President Franklin Roosevelt signs the Ramspeck Bill on Nov. 26, 1940 at Washington, D.C., authorizing him to add 200,000 federal emergency agency employs to civil service lists. Left to right: Rep. Robert Ramspeck (D-Ga.), Sen. James Mead (D-NY), the President and Rep. Jennings Randolph (D-WVA). President Franklin Roosevelt signs the Ramspeck Bill on Nov. 26, 1940 at Washington, D.C., authorizing him to add 200,000 federal emergency agency employs to civil service lists. Left to right: Rep. Robert Ramspeck (D-Ga.), Sen. James Mead (D-NY), the President and Rep. Jennings Randolph (D-WVA). (AP Photo)

In that same speech, Rubio hailed the Can Do national spirit of World War Two, which persisted into the Cold War:

What I am calling for us to do is remember that from World War II to the Space Race and beyond, a capitalist America has always relied on public-private collaboration to further our national security.

Rubio added that at the heart of this nationalist spirit is a common commitment to building better technology; this tech, he added, oftentimes radiates from the military and industry to society as a whole:

From the internet to GPS, many of the innovations that have made America a technological superpower originated from national defense-oriented, public-private partnerships.

And yet, Rubio continued, these partnerships should include more than just capitalists, scientists, and technologists; partnerships should also include workers:

It is a call to encourage and harness the dynamism of our economy’s most productive private industries to further our national security and ultimately our national economic development. It is a call for a 21st-century pro-American industrial policy.

Once again, Rubio’s argument is apple-pie common sense: After all, Uncle Sam never could have maintained the national unity needed—for hot wars and cold wars—without taking positive steps, here at home, to include everyone into the effort. As our motto says, e pluribus unum (out of many, one); when national survival is at stake, oneness is vital. So if we want the population to fight, to work, and to win, then it must be a people’s war. As the posters for the famous Iwo Jima Bond Drive in World War Two declared, “Now All Together.”

Yet here again, some folks at National Review don’t agree. For instance, Daniel Tenreiro worried that Rubio’s ideas might have the effect of “decreasing shareholder rights.” Okay, it’s to be expected that libertarian leaners would always be looking out, first, for the interests of capital—even though Rubio has been at great pains, in all his pronouncements, to defend capitalism and the free-enterprise system.

Yet what was un-expected was the line of attack from another National Review man, Robert VerBruggen; he played the politically correct gender card, his piece was headlined, “Is America Ready for a ‘Good Jobs for Men’ Plan?” Indeed, VerBruggen charged right in: “The gender politics of ‘industrial policy’ could prove toxic.”

Then VerBruggen got to the nut of his argument: “Because industrial policy generally focuses on manufacturing, it’s likely to provide good jobs disproportionately for men.” Men, of course, are often deemed to be dubious, PC-wise.

To be sure, VerBruggen has a point when he says that the politics of Rubio’s economic nationalism should be handled “deftly”—although, of course, that’s true for anything; deft handling is always a good idea. Yet by raising the alleged “toxicity” of Rubio’s idea, the National Review writer is actually making it all the more difficult to achieve re-industrialization. That is, leftist and green critics can now point to VerBruggen’s article and say, “See? Even right-wingers say that Rubio’s ideas are ‘toxic.’”

Moreover, it’s hardly the case that all factory jobs go to men; going back to World War Two, who can forget “Rosie the Riveter”? And since then, even the heaviest of heavy industries today include robots and other machines doing much of the hard labor. Factory work is still demanding, but women can do it, too.

As we can see, National Review seems to be hardening its face against Rubio; some are suggesting that he’s a fascist, others say he’s not nice enough to shareholders, and yet others accept a parody-feminist vision of industry. (In fairness, Rubio had a defender at the magazine; Fred Bauer helpfully opined that Rubio’s ideas are“far from radical.”)

Yet National Review’s overall stance against Rubio inspired Harvard Law School professor Adrian Vermeule to issue a tart tweet:

The prospect of government acting to promote the common good has driven Conservatism Inc. into the arms of woke capitalism.

And Rubio himself responded to VerBruggen:

Why would I stop pointing to the obvious, that growth in American manufacturing jobs would help millions of working age American men finding good or better jobs. And why would that be bad for anyone?

Good question!

While we are on the subject of Rubio and the common good, we might take a moment to reflect on the deep roots of the word “common,” both in American history and in the Christian tradition.

The word “common” is right there in the Preamble of the Constitution: The new nation declares that it will “provide for the common defense.” Indeed, four U.S. states–three of them among the original Thirteen Colonies—are officially cited as “commonwealths.”

Indeed, “common” reaches even further back, deep into mists of Anglo-Saxon law.

And here in this side of the Atlantic, John Winthrop, leader of the Puritans coming to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, declared that the new political and cultural system would be dedicated to “the glory of [the] Creator and the common good of the creature, Man.” Thus the Boston Common was established in 1634; today, it’s the oldest public park in the United States.

We might add that William Jennings Bryan—who served in Congress, led a unit of Nebraska volunteers mobilized for the Spanish-American War, and later capped his public career as secretary of state—was known, admiringly, as “The Great Commoner.” Bryan is best remembered, of course, for being the Democratic presidential nominee in 1896, 1900, and 1908. For two decades, his common touch made him the soul of the Democratic Party.

In addition, the word “common”—from the Greek koinos, from which we also get the word coin, as in “coin of the realm”—is oft-cited in the New Testament. For instance, there’s Titus 1:4. in which Paul addresses one of his Christian followers: “Titus, mine own son after the common faith: Grace, mercy, and peace.”

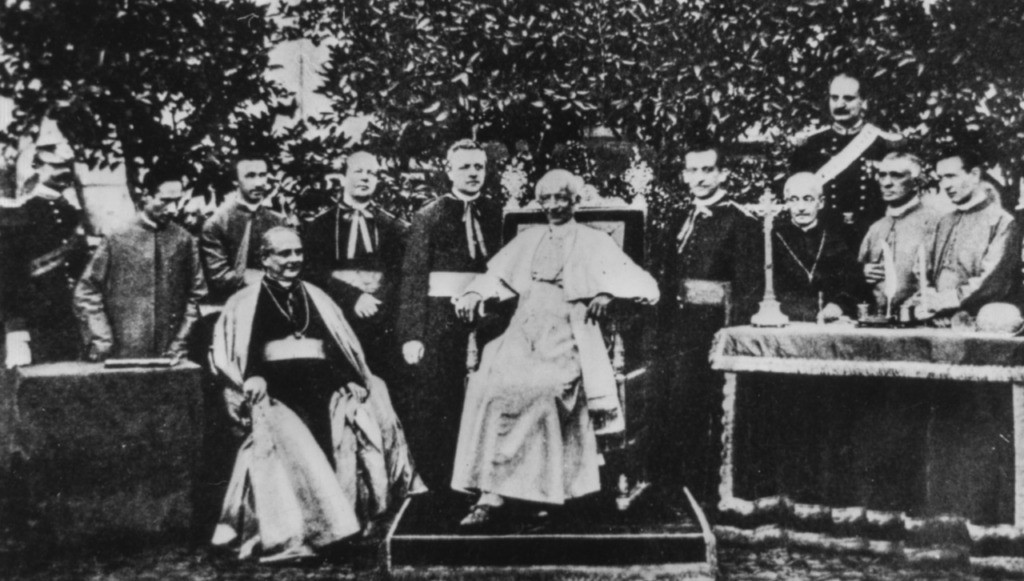

Interestingly, Rubio has specifically linked his “common good” theme to another religious figure, Pope Leo XIII, who led the Roman Catholic Church from 1878 to 1903. Leo is best remembered for his 1890 encyclical, Rerum Novarum, which spelled out, in theological terms, the social obligations of both capital and labor.

Pope Leo XIII (centre) with members of the Papal Secretariat in the garden of the Vatican, Rome, circa 1900. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In that document, the words “common,” “commonweal,” and “commonwealth” appear 38 times. Yet at the same time, Leo was careful not to allow any conflation of common good and common ownership. As he wrote,

It is clear that the main tenet of socialism, community of goods, must be utterly rejected, since it only injures those whom it would seem meant to benefit, is directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind, and would introduce confusion and disorder into the commonweal.

In other words, Leo was in favor of a common faith, and believed in common values for the community, and yet he was also staunchly in favor of responsible private property and the properly regulated workings of the free market.

Leo’s Rerum Novarum is one of the foundational texts of the right-of-center Christian Democratic political parties across Europe; indeed, the ideas of Rerum have spread to the whole world.

As Rubio wrote recently in First Things, Leo’s vision “sees past our stale partisan categories and roots our politics in something larger: the inviolable dignity of every human person, the work he or she does, and the family life that work supports.”

Building from this tradition of economic balance and social harmony, Rubio has now added another component: the imperative of robust technology as a vital underpinning of national security.

As we have seen, not everyone likes what Rubio is doing, and yet even so, it’s clear that he’s playing a winning hand—for himself, and for his country.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.