Retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman to serve on the Court, passed away Friday in Phoenix, Arizona, at the age of 93, after suffering complications of dementia.

The official statement from the Supreme Court identified O’Connor as “the first female member of the Court,” a definition that might not sit well with the Court’s newest and most junior member, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who famously declined in her Senate conformation hearing to say what a “woman” is.

Nevertheless, O’Connor was indeed a pioneer. She was nominated in 1981 — not by a liberal Democrat, but rather by President Ronald Reagan, the archetypal conservative Republican.

Supreme Court Justice-designate Sandra Day OConnor (right) poses with first lady Nancy Reagan, Chief Justice Warren Burger, and President Ronald Reagan during a reception at the White House on Sept. 24, 1981. (AP Photo)

She was unanimously confirmed — though, as with many nominations of women and minorities by Republicans, her nomination irked the left, which believes members of those communities have a duty to back redistributionist policies, such as affirmative action, that ensure their representation among elites, public and private.

Arizona judge Sandra Day O’Connor testifies at her confirmation hearing as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court before the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 1981. (Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

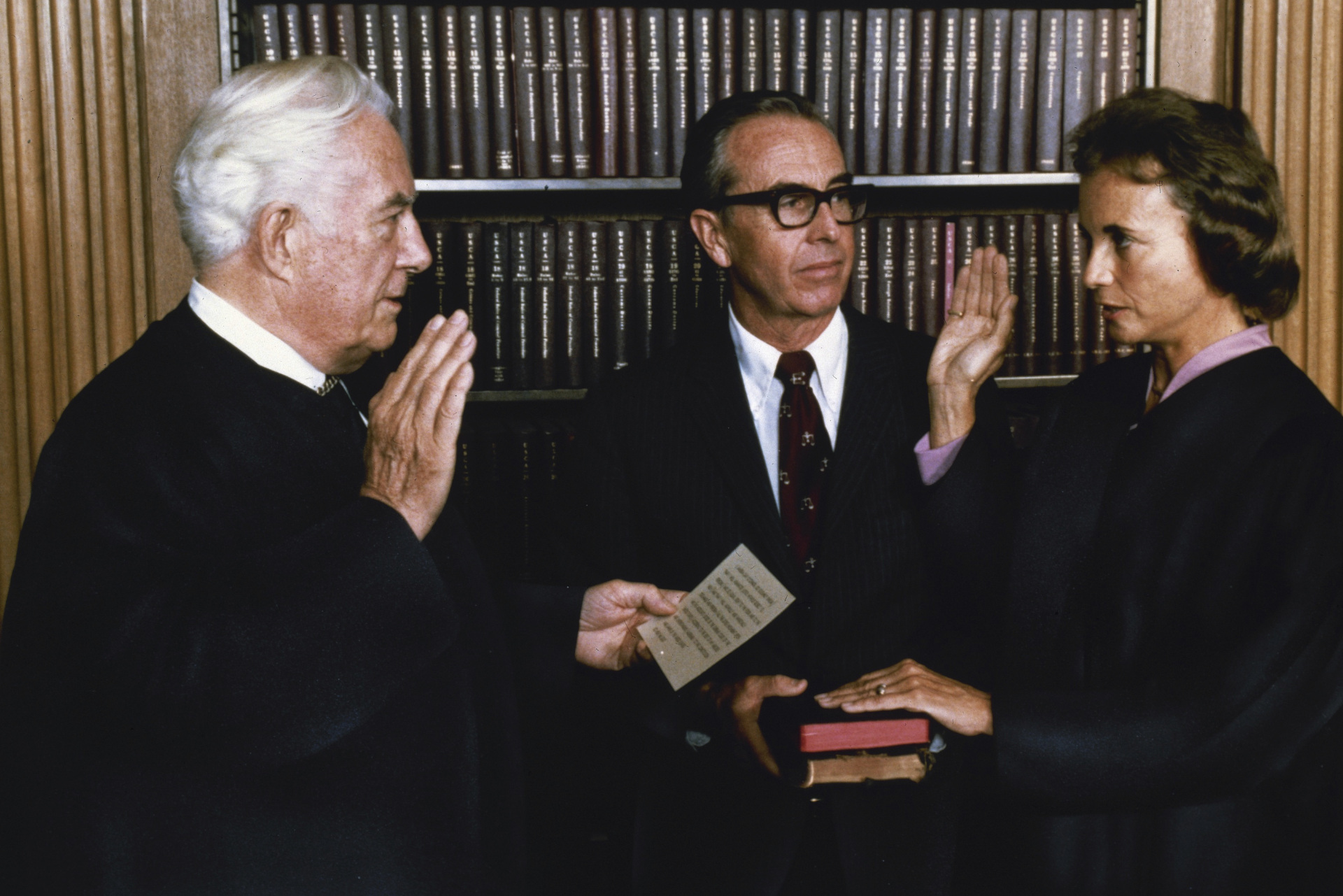

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female justice of the Supreme Court, is sworn in by Chief Justice Warren Burger in the court’s conference room in Washington on Sept. 25, 1981. (AP Photo/The White House)

As it happened, O’Connor did back affirmative action. In 2003, she wrote the majority opinion for a divided 5-4 Court in Grutter v. Bollinger, upholding the use of race in admissions at the University of Michigan Law School. But she noted “that all race-conscious admissions programs have a termination point … We expect that 25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.” That point came earlier this year, when the Court overturned racial preferences in college admissions.

O’Connor was also known for steering a moderate path on abortion. She rejected the trimester approach of Roe v. Wade (1973), but still backed a “right” to abortion, though she allowed that it could be restricted by legislation.

She also earned criticism from conservatives, and praise from liberals, for opposing religious displays on public property. “Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?” she wrote in a concurring opinion in McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky.

Conservatives did not like O’Connor’s approach, often described as pragmatic by those who admired her. But they did not feel a sense of betrayal: she had never been presented to them as an ideological ally.

In the early 1980s, the nasty fight over Robert Bork — initiated in part by Sen. Joe Biden (D-DE) — had not yet happened, and judicial doctrine was not a key part of confirmations.

O’Connor was born in El Paso, Texas, and studied at Stanford Law School, where she briefly dated future Chief Justice William Rehnquist. She took time out from her legal career to become a stay-at-home mother, then returned to the political and judicial arena.

When Reagan nominated her to the Supreme Court, she had only been on the Arizona Court of Appeals for two years. That led some to doubt her qualifications; those doubts continued to surface when people did not agree with her rulings on the bench.

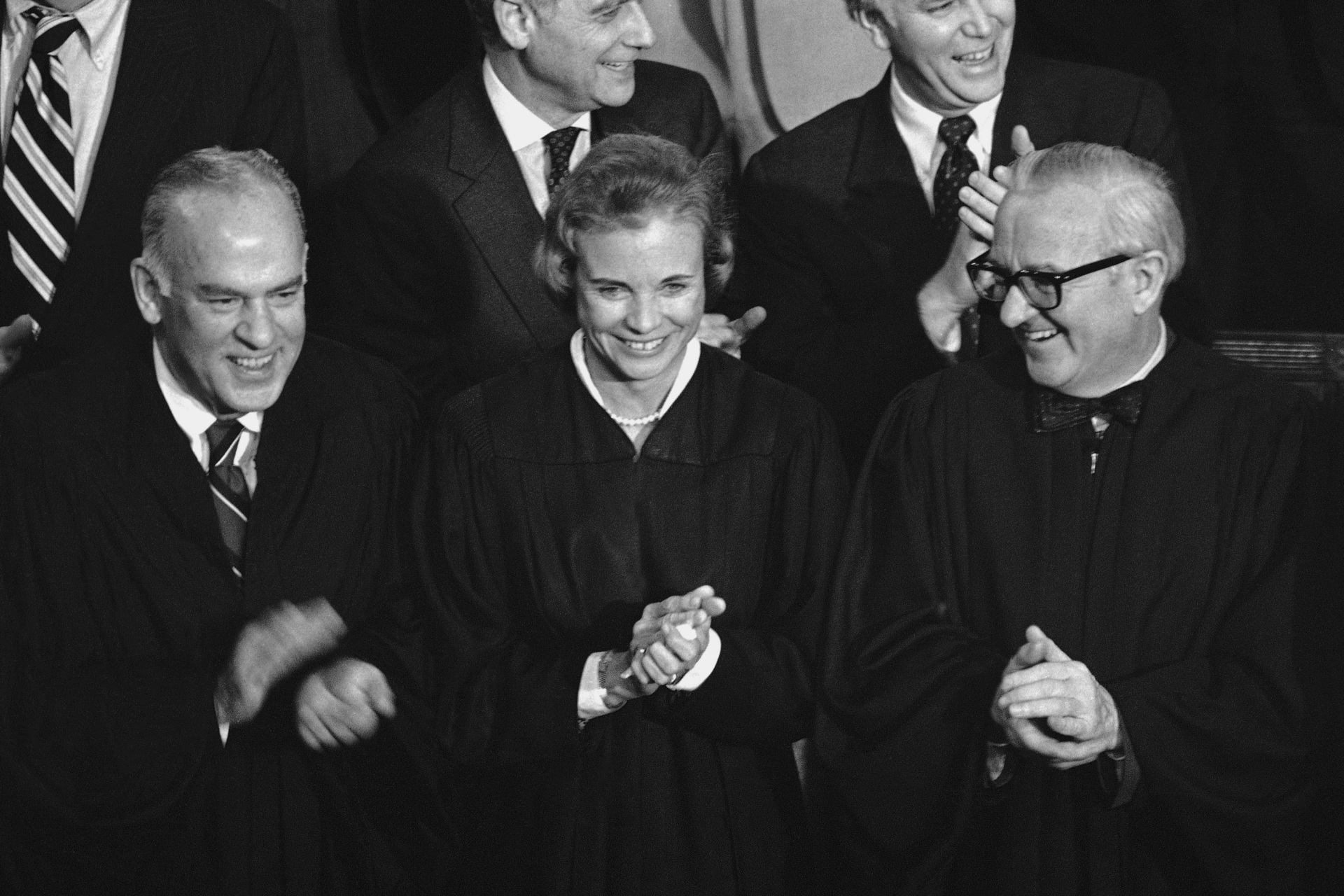

Former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart (left) and his replacement on the court Justice Sandra Day O?Connor applaud President Reagan as he gives his State of the Union address on Jan. 26, 1982. (AP Photo)

But O’Connor won respect as one of the last justices who considered cases on their merits, a throwback to a time before the Court was seen as a political body composed of representatives of the administrations that nominated them.

She happened to side with Republican appointees in Bush v. Gore (2000), a case that the left still sees as a provocation. But when she retired five years later, she was seen as her own person, not a tool of any party or philosophy.

So she remains: a unique figure in American jurisprudence.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News and the host of Breitbart News Sunday on Sirius XM Patriot on Sunday evenings from 7 p.m. to 10 p.m. ET (4 p.m. to 7 p.m. PT). He is the author of the new biography, Rhoda: ‘Comrade Kadalie, You Are Out of Order’. He is also the author of the recent e-book, Neither Free nor Fair: The 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.