The 80th anniversary of the end of World War II is coming soon. On September 2, 1945, aboard the battleship U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Japanese officials signed an instrument of unconditional surrender.

Yet along the path to that rendezvous with anniversary come important milestones—such as the first detonation of an atomic bomb on July 16, 1945.

Most observers agree it was the A-bomb that finally forced Japan to surrender, shortening the fighting in the Pacific by several years.

Indeed, until the atomic attacks, the Japanese were full of fight. On April 1, 1945, U.S. forces landed on Okinawa, 400 miles south of Japan’s home islands. More than 100,000 defenders, including women and children, put up a fierce fight. Over the 11-week campaign, some 94,000 of those defenders died, inflicting 50,000 casualties on the Americans.

According to the U.S. Naval Institute, “Okinawa’s death toll horrified U.S. political leaders,” leading military planners to anticipate that the looming assault on Japan could cause half a million American casualties—just to capture Kyushu, one of four main Japanese home islands (there are more than 14,000 islands, total). Said the diehard defenders: “We will fight till we eat stones.”

But nobody in Japan—and precious few in the U.S.—knew about the atom bomb, which the U.S. had been working on since Albert Einstein wrote a fateful letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 2, 1939. Sketching the rudiments of atomic power to the commander-in-chief, Einstein asserted, “A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.”

Einstein’s letter got attention, even if the bomb-building effort didn’t begin in earnest until the Manhattan Project was launched in mid-1942. It was a massive undertaking, employing 600,000 Americans, from machinists to typists to physicists.

And because it hired so many people, it had its share of quirky human moments. In his prize-winning 1986 history, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, Richard Rhodes captured the epic sweep of the mission, including its weirdness. He quoted J. Robert Oppenheimer, lead scientist at the bomb-assembly site that that sprang up amidst the dusty alkaloid badlands of New Mexico:

People at Los Alamos were naturally in a state of some tension. I remember one morning when almost the whole project was out of doors staring at a bright object in the sky through glasses, binoculars and whatever else they could find; and nearby Kirtland Field reported to us that they had no interceptors which had enabled them to come within range of the object. Our director of personnel was an astronomer and a man of some human wisdom; and he finally came to my office and asked whether we would stop trying to shoot down Venus. I tell this story only to indicate that even a group of scientists is not proof against the errors of suggestion and hysteria.

As an aside, this anecdote, humorous in retrospect, reminds us that scientists can be great at what they do and still need supervision on everything else.

Yet because Oppenheimer’s eccentrics were good at nuclear physics, the first atomic bomb, code-named Trinity, was successfully detonated on July 16, 1945. Surely one of the most dramatic moments in human history, it was recorded in real time and recalled in many movies since, including the Oscar-winning film Oppenheimer.

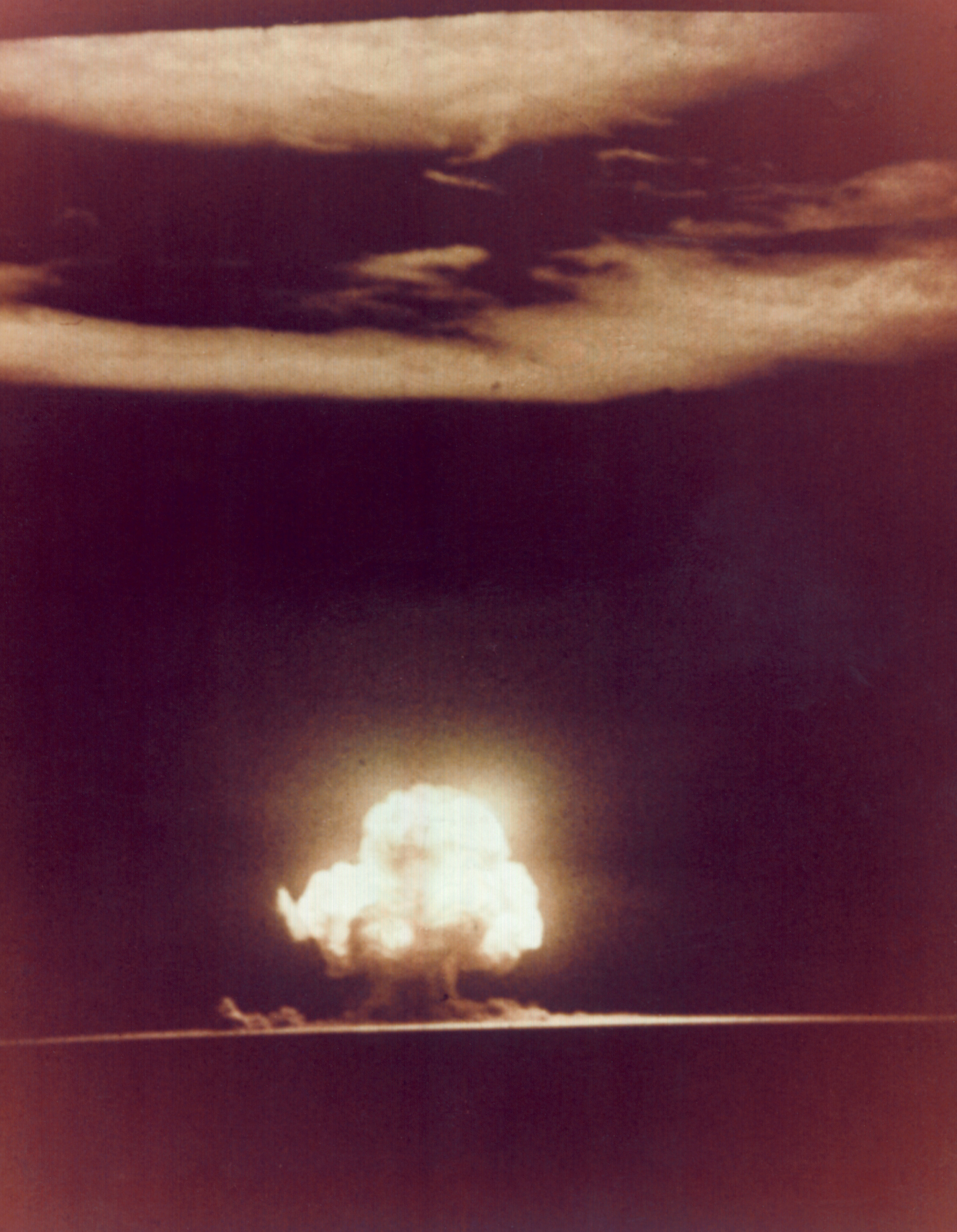

Historian Rhodes cites one eyewitness: An “ominous cloud hanging over us. It just seemed to hang there forever . . . It was so brilliant purple, with all the radioactive glowing.” Somewhat unnecessarily, he added, “It was very terrifying.”

Physicist Norris Bradbury sits next to “The Gadget,” which was the nickname the Los Alamos scientists gave the nuclear device they created, at the top of the test tower at the Trinity test site in New Mexico in July 1945. (Corbis via Getty Images)

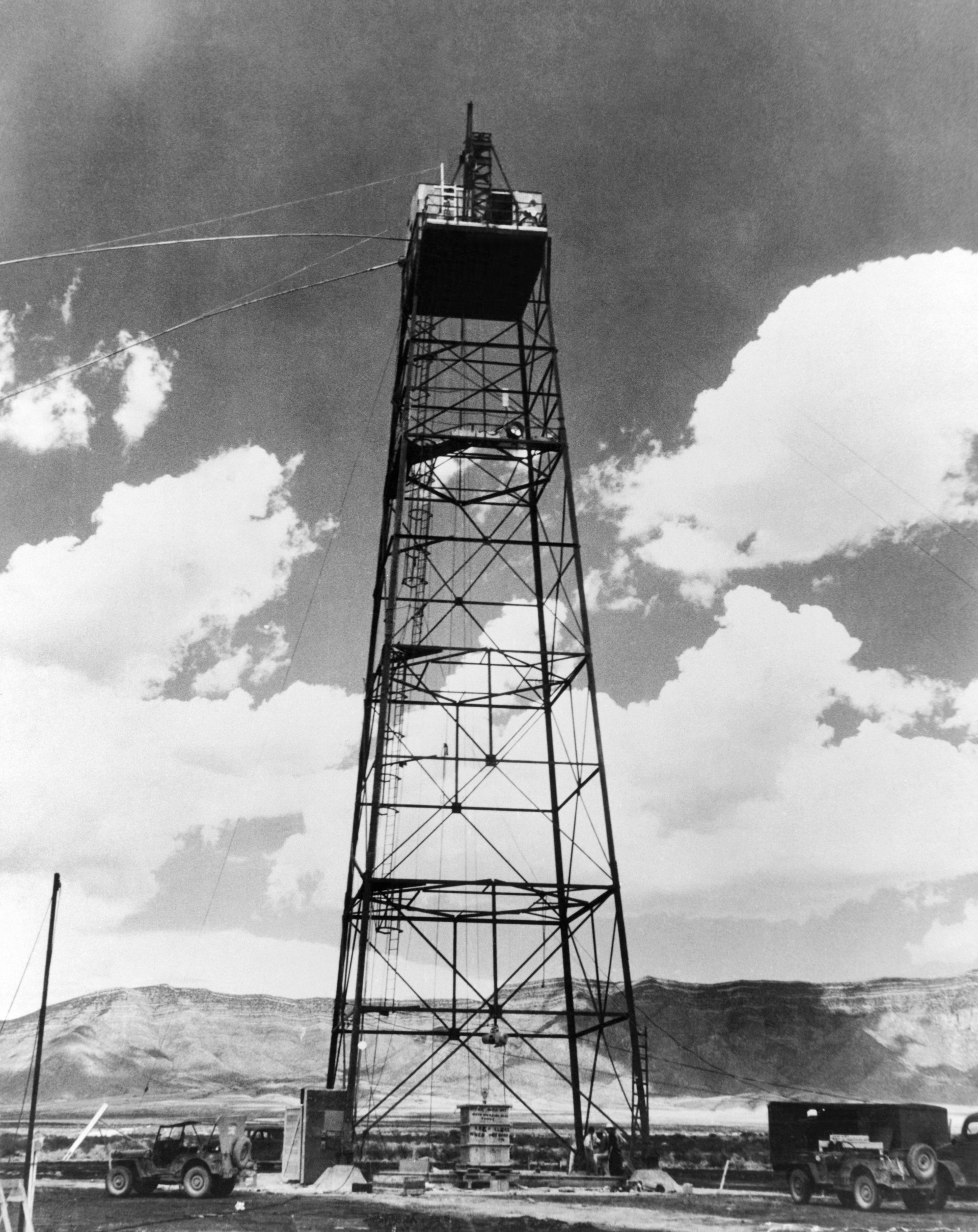

View of the bomb tower at the Trinity nuclear test site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

The Trinity test bomb is unloaded at the base of the tower for the final assembly in July 1945. (U.S. Department of Energy)

A photo of the first ever detonation of a nuclear device at the Trinity nuclear test site on July 16, 1945. This unofficial photo was taken by Manhattan Project scientist Jack Aeby on a still camera loaded with color movie film. (Jack Aeby/Corbis via Getty Images)

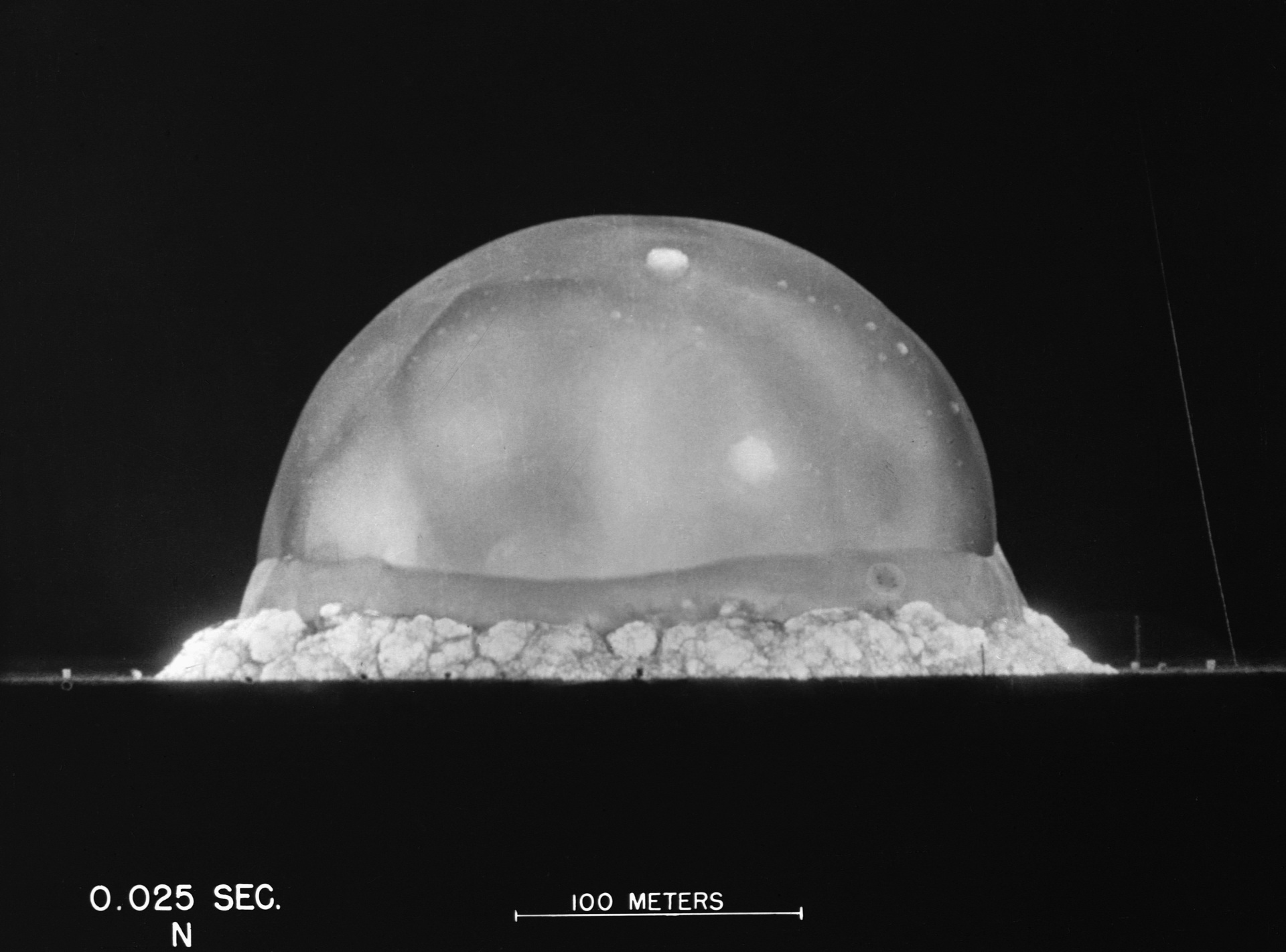

A photo of the Trinity Test bomb’s mushroom cloud at 0.025 seconds after detonation. (Corbis via Getty Images)

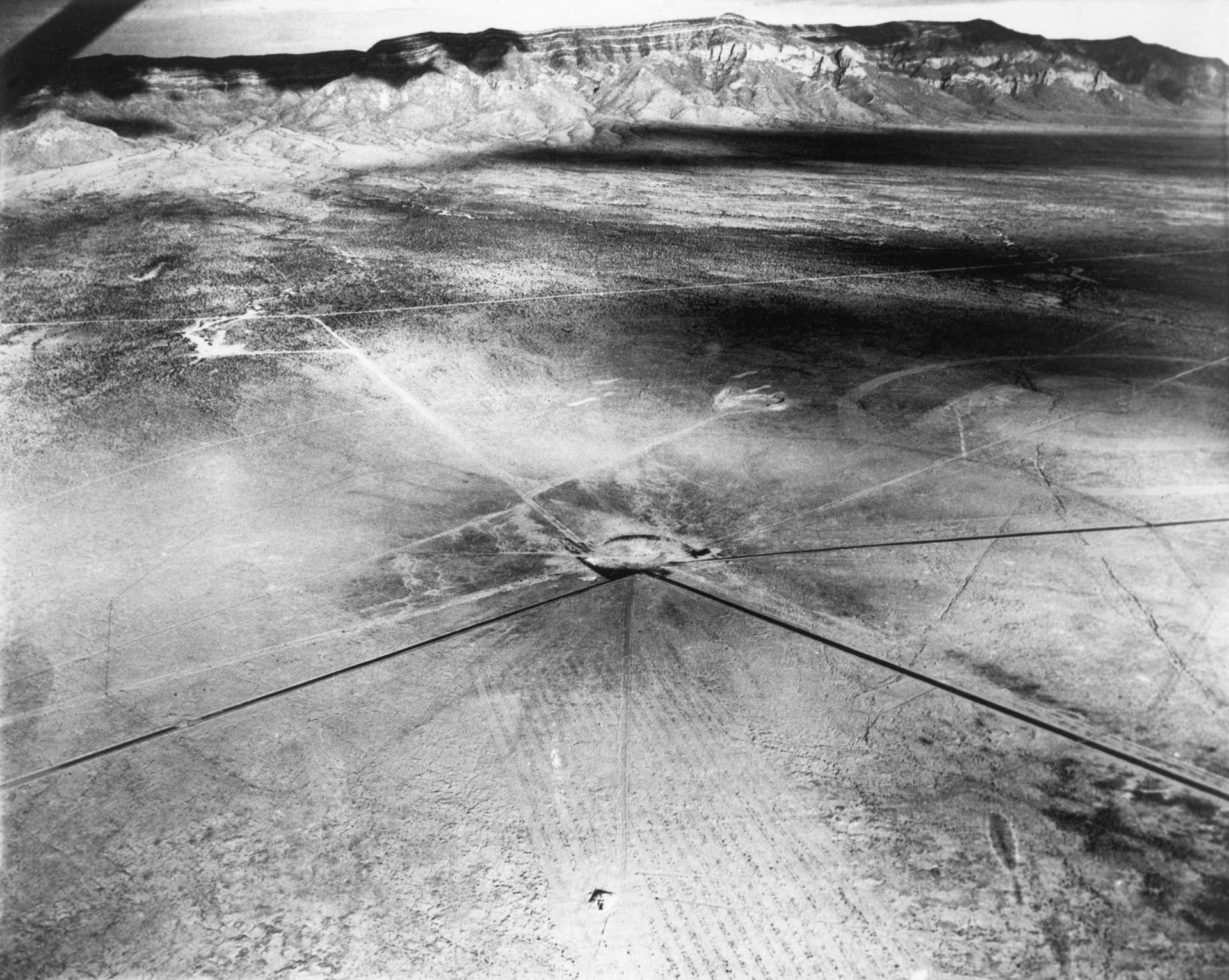

An aerial view taken on September 11, 1945, of the Trinity atomic bomb testing site in New Mexico, showing the shallow crater dug by the blast 300 feet around the tower from which the bomb hung. The sand in an area 2,400 feet around the tower was seared into jade green glasslike cinders. The area devastated by the bomb measures 4,800 feet in diameter, and the steel tower was entirely disintegrated. (Getty Images)

Scientist Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves examine the remains of one the bases of the steel test tower at the Trinity test site in September 1945. (Getty Images)

As it happened, July 16, 1945 was the day that President Harry Truman had arrived in Potsdam, Germany. Two months earlier, the Nazis had surrendered, and now the 33rd president—himself just in office for just three months, since FDR’s death in April—was joining a summit conference to settle the future of Europe, alongside British leader Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Josef Stalin.

Truman, always suspicious of communists, was guarded in his conversations with the Red Tsar, saying only that the U.S. had just developed “a new weapon of unusual destructive force.” For his part, Stalin reacted with impassivity; he already knew about the bomb—Soviet spies having tipped him off.

Within the U.S., there was some hesitation about using the A-bomb. Was it right to wield a weapon so deadly? To set a new precedent for mass destruction? In particular, leftists were concerned that if the U.S. had the A-bomb and the Soviets did not—having the plans was not the same as actually making one, it took the Russians until 1949—then the capitalists would have more strength than the communists.

Yet Truman himself never had any hesitation about the bomb. He wanted the war to end with a U.S. victory as quickly as possible.

So now the mission was getting A-bomb number two, dubbed “Little Boy,” into position.

The commander of strategic booming in the Pacific, Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, was blunt: “I’ll tell you what war is about, you’ve got to kill people, and when you’ve killed enough they stop fighting.” LeMay’s weapon of choice: The B-29 Superfortress.

The commander of the atomic mission was Col. Paul Tibbets, who named his plane after his mother, Enola Gay. (The subject, four decades later, of a haunting pop song.)

Tibbets’ 12-hour mission to Hiroshima and back was a success. That day, Truman issued a tough statement:

The Japanese began the war from the air at Pearl Harbor. They have been repaid many fold. And the end is not yet. With this bomb we have now added a new and revolutionary increase in destruction to supplement the growing power of our armed forces. In their present form these bombs are now in production and even more powerful forms are in development.

Yet even after an estimated 70,000 to 140,000 had died at Hiroshima, the Japanese government had not surrendered. So, on August 9, Truman dropped a second A-bomb, this one on Nagasaki, which killed an estimated 39,000 to 70,000.

Seeing the absolute annihilation of his nation in prospect, Emperor Hirohito was ready to surrender, which he did on August 15.

The A-bomb ended the war sooner, potentially saving more lives than those lost in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

However, when Oppenheimer met Truman in the Oval Office, he gave vent his misgivings about the whole effort: “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” Truman dismissed him, saying to aides later, “I never want to see that crybaby again.”

This photo from 1961 shows the simple stone monument that marks the Trinity test site in Alamogordo, New Mexico. The plaque reads: “TRINITY SITE. WHERE THE WORLD’S FIRST NUCLEAR DEVICE WAS EXPLODED ON JULY 16, 1945.” (Getty Images)

Tourists in 2010 visit the Trinity test site on the White Sands Missile Band in the desert of New Mexico. Because it is still an active military site, the location is only open twice a year to visitors, on the first Saturdays of April and October. (Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

A different take on the bomb came from another American, Paul Fussell. As a young man, Fussell had served as a 2nd Lt.. in the 103rd Infantry Division, fighting against Hitler, where he saw plenty of his comrades die. His unit had been slated to fight next in Japan, but happily for Fussell and millions of other GIs, those plans were cancelled after Japan surrender. Decades later, Fussell, by now a well-regarded professor at Princeton, summed up his feelings in a bluntly titled tome, Thank God for the Atom Bomb.

Today, on a limited basis, the Trinity Site is open to the public. So, all Americans can visit the place where the atomic age began.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.