Conservative scholar and talk radio host Mark Levin reminded Americans, including left-wing liberals and even some Republicans, that the late labor leader Cesar Chavez did not think it was compassionate to enable and encourage illegal immigration.

Levin noted that in addition to Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Harry Truman and civil rights icon Ralph Abernathy, who was Martin Luther King’s top adviser, Chavez — who is lionized by Hispanics, the left, and the labor movement — opposed illegal immigration “virulently.”

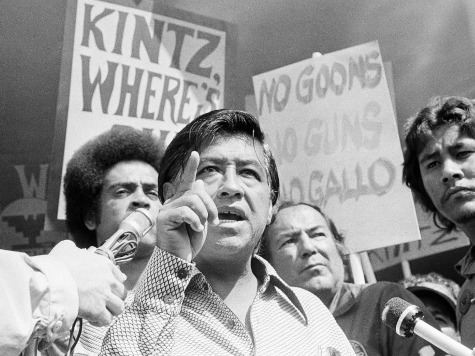

“Cesar Chavez opposed illegal immigration,” Levin said during a Wednesday appearance on Fox News’ Hannity.

After saying that the premise that “compassion is an open border” is a “new idea” that has been pushed in recent times, Levin said that “a nation has a right to secure its border” and its citizens have a right to know who is coming into their country.

Chavez, who was also against ethnic organizations like La Raza, would tell illegal immigrants to get out of the country, especially because they lowered the wages of American workers. And he was often far from compassionate in handling illegal immigrants.

As Breitbart News has reported, “Chavez was so opposed to amnesty that even the film’s producers, who have a history of making politicized movies, decided, out of respect, to steer clear of the subject”:

As the New York Times noted, Participant Media, which produced the film, has a “fondness for films about social issues.” The company made Lincoln as a statement about bipartisanship, The Help to “highlight the plight of domestic workers,” and Promised Land as a “call for environmental action” against fracking.

But the producers avoided immigration reform in the movie because Chavez “fought for better wages and conditions for workers but held complex and evolving views on the status of unauthorized immigrants, some of which would be at odds with the changes many Hispanics and others are seeking today.”

Breitbart News has also detailed how much Cesar Chavez opposed amnesty:

Ruben Navarrette, Jr., a supporter of comprehensive immigration who has “studied and written about Chavez and the United Farm Workers … for more than 20 years,” wrote in a 2010 essay that “the historical record shows that Chavez was a fierce opponent of illegal immigration.” He added that “it’s unlikely that he’d have looked favorably on a plan to legalize millions of illegal immigrants.”

Chavez also wanted stiffer sanctions against employers who hired illegal immigrants, and Navarrette emphasized that it was “absurd for anyone to invoke the name of Cesar Chavez to pass immigration reform.” He stressed, “As I said, were he alive today, it’s a safe bet that Chavez would be an opponent of any legislation that gave illegal immigrants even a chance at legal status.”

Navarrette wrote that, according to numerous historical accounts, “Chavez ordered union members to call the Immigration and Naturalization Service and report illegal immigrants who were working in the fields so that they could be deported.”

He noted that while Chavez was with the UFW, “UFW officials were also known to picket INS offices to demand a crackdown on illegal immigrants,” and the UFW even “set up what union officials called a ‘wet line’ to stop Mexican immigrants from entering the United States. Under the supervision of Chavez’s cousin, Manuel, UFW members tried at first to convince immigrants not to cross the border”:

When that didn’t work, they physically attacked the immigrants. Covering the incident at the time, the Village Voice said that the UFW was engaged in a “campaign of random terror against anyone hapless enough to fall into its net.” A couple of decades later, in their book The Fight in the Fields, Susan Ferris and Ricardo Sandoval recalled the border violence and wrote that the issue of how to handle illegal immigration was “particularly vexing” for Chavez.

Chavez was also against ethnic groups like La Raza. In fact, he saw the dangers of such organizations from the beginning.

“I hear more and more Mexicans talking about la raza–to build up their pride, you know,” Chavez told Peter Matthiessen, the co-founder of the Paris Review, for a profile piece in The New Yorker in 1969. “Some people don’t look at it as racism, but when you say ‘la raza,’ you are saying an anti-gringo thing, and it won’t stop there.”

Chavez continued in the interview:

Today it’s anti-gringo, tomorrow it will be anti-Negro, and the day after it will be anti-Filipino, anti-Puerto Rican. And then it will be anti-poor-Mexican, and anti-darker-skinned Mexican. We had a stupid guy who just wanted to play politics with the union, and he began to whip up la raza against the white volunteers, and even had some of the farm workers and the pickets and the organizers hung up on la raza. So I took him on. These things have to be met head on.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.