Rwanda marked on Friday the 29th anniversary of the 1994 genocide of ethnic Tutsis, a nationwide massacre that lasted 100 days and killed over 1 million people.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame, a Tutsi who rose to power after his Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) seized control of the country and stopped the genocide, observed the anniversary by reminding Rwandans that the lesson of the episode of horror was, “You are on your own.”

“Remember that in the time of need when we needed every help we could get, the world turned its back on us,” Kagame said in an address on Friday to mark the Kwibuka, the remembrance ceremony the country holds every year for the victims of the genocide. “Kwibuka” means “remember” in the predominant Kinyarwanda language.

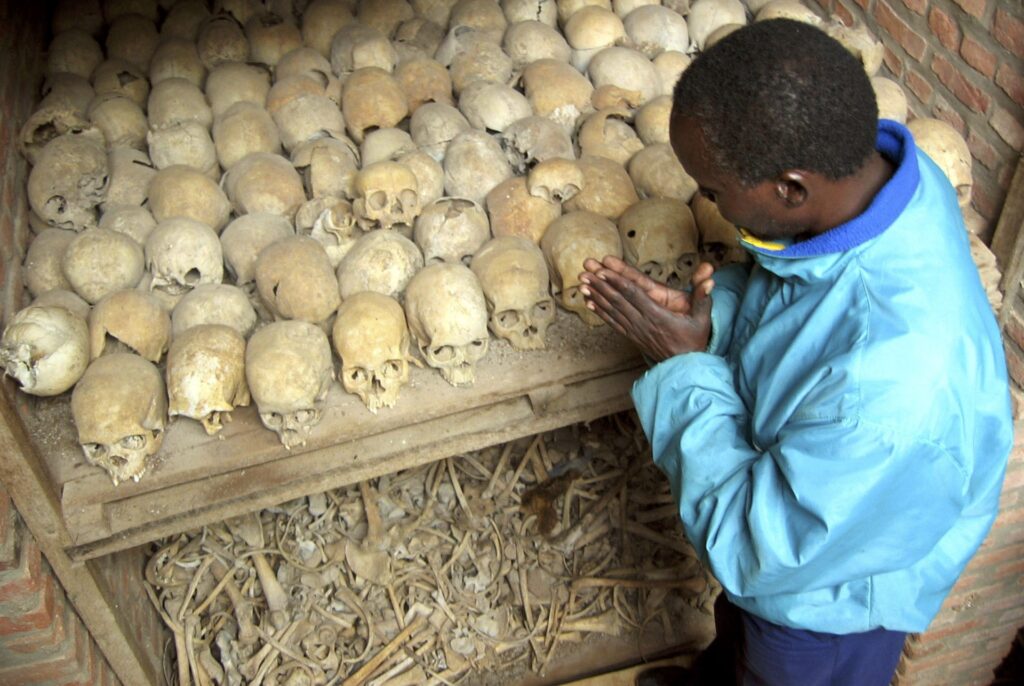

A Rwandan survivor of the 1994 genocide prays over the bones of genocide victims at a mass grave in Nyamata, Rwanda, April 6, 2004. Genocide survivors in Rwanda welcomed the conviction in France of Laurent Bucyibaruta, a former official in this East African country whose current leaders are pressing for the arrest and trial of all genocide suspects still at large in Europe. (AP Photo/Sayyid Abdul Azim-file)

“The message is ‘You are on your own,’ so we should learn to be on our own and I think we have learnt enough,” Kagame said.

On a more positive note, Kagame applauded his people for working to “transform challenges into opportunities and also use so little to do a lot. There is nothing Rwandans cannot overcome through unity, hard work, and perseverance.” He also used the opportunity to warn against “hate speech,” citing the widespread propaganda urging ethnic Hutus to kill Tutsis during the genocide as an example of what can happen if hate speech is not controlled.

“People have managed to turn the page and move forward from grieving, crying and have decided to live on and even willing to do the most difficult thing one way or the other, they have decided to forgive but we can’t forget,” Kagame said. “We cannot, however, ignore that things like violence and hate speech persist not far away from here. Much as it does so, you can also see the same indifference today as we saw in 1994.”

Hutus are the vast majority of the population of Rwanda, and were before the genocide. The country was experiencing significant ethnic strife in 1993, which President Juvénal Habyarimana attempted to address through peace talks. Habyarimana, a Hutu, and fellow ethnic Hutu President Cyprien Ntaryamira of Burundi, were both killed on April 6, 1994, as a result of their plane en route to peace negotiations being shot down. Hutu agitators used mass media to blame the RPF and Tutsis generally for the deaths and actively encouraged the mass killing of Tutsi people. Radio broadcasts enthusiastically referred to Tutsis as “cockroaches” and called for their extermination – identifying people by name that broadcasters wanted killed for being Tutsis and echoing genocidal anti-Tutsi propaganda that had been spreading throughout the previous year.

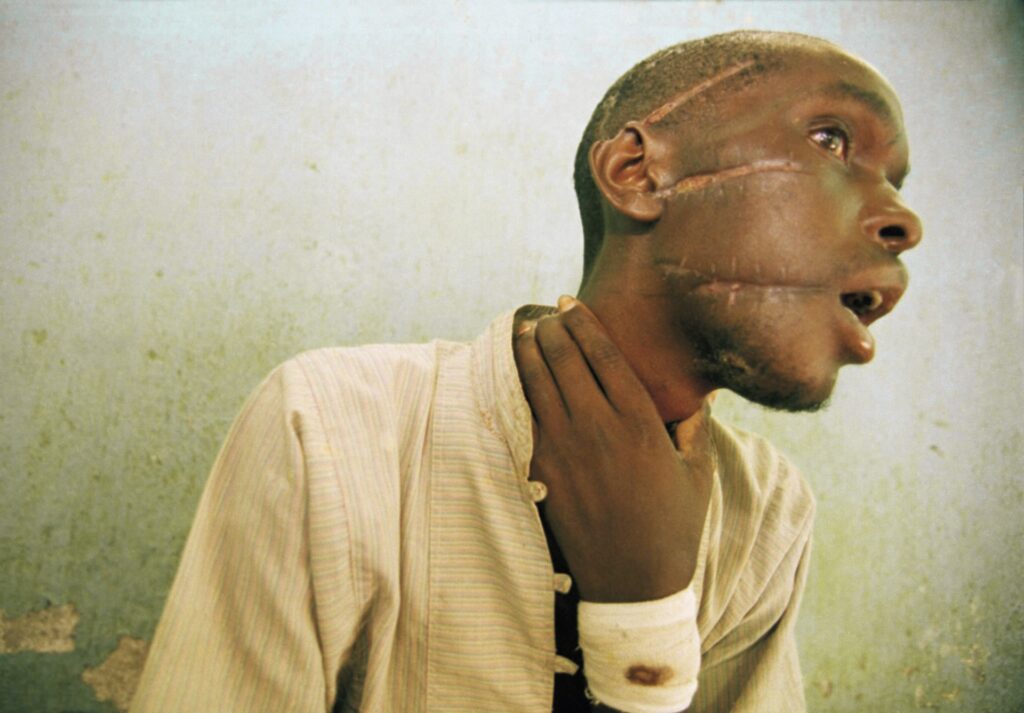

Nyabimana (first name unknown), 26, shows machete wounds at an International Committee of the Red Cross Hospital in Nyanza, some 35 miles southwest of Kigali, Rwanda, on June 4, 1994. (Jean-Marc Bouju, File/AP)

“We began by saying that a cockroach cannot give birth to a butterfly. It is true. A cockroach gives birth to another cockroach,” an article in the Rwandan newspaper Kangura declared in 1993. “The history of Rwanda shows us clearly that a Tutsi stays always exactly the same, that he has never changed. The malice, the evil are just as we knew them in the history of our country.”

Many civilian Hutus took up rudimentary arms against their Tutsi neighbors – clubs and machetes were especially popular – and indiscriminately killed them. The use of rape to humiliate and torture Tutsi women was also common. The use of machetes left Rwanda with tens of thousands of survivors who escaped but had limbs or other body parts hacked off of them.

“I learned during the genocide my Hutu neighbors — the same neighbors whose children I grew up playing with, the same group of neighbors who used to come to my family home for food and drink, the same group of neighbors who used to attend the same churches,” Jaqueline Murekatete, a genocide survivor, recalled in 2019, “these same people had taken my parents and all my six siblings to a nearby river where they proceeded to murder them one by one and throw their bodies in the river.”

Jacqueline Murekatete, 19, waits for an interview outside the halls of the General Assembly, after speaking to its members, during the “International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda” at the United Nations in New York, Wednesday, April 7, 2004. (Bebeto Matthews/AP)

Murekatete, who spoke at an event that year marking the 25th anniversary of the genocide, blamed the length of time the massacre continued on a “lack of political will to stop” the killings.

“We could have actually saved hundreds of thousands,” Romeo Dallaire, the head of the United Nations peacekeeping force in Rwanda at the time, told the left-wing news outlet CNN in 2008. Dallaire, who went on to serve as a senator in his native Canada and launch a charity to save child soldiers, demanded that the U.N. send him sufficient forces to suppress the violence and greenlight action to stop it, but has repeatedly testified following the genocide that his bosses ignored him.

In the CNN interview, Dallaire said that he was aware as early as January 1994 that an organized attempt by Hutu leaders to massacre Tutsis had been planned. The Kagame government also maintains that the genocide was planned and not a random outburst of violence.

He requested the U.N. to launch an operation against Hutu militias to prevent a catastrophe, but did not receive approval. Once the genocide began, the U.N. debated for weeks before the Security Council voted to diminish Dallaire’s forces by 90 percent and, two weeks later, order him to withdraw completely, an order Dallaire disobeyed.

“When you’re operating in that sort of context with limited troops and facilities, you have to be careful what sort of risks they take, where everybody may even have to leave, and place a people at greater risk. And in a way, this is what happened,” Kofi Annan, who ran peacekeeping operations at the time, told CNN about Dallaire’s initial request for an operation against the Hutu extremists and why he denied it. Annan would later be promoted to U.N. Secretary-General.

On Friday, Kagame and First Lady Jeannette Kagame laid wreaths at a monument to the genocide victims in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, and held a ceremony retelling the history preceding the massacres.

Rwanda’s New Times detailed the itinerary:

The commemoration events are expected to start with a lighting of the ‘Flame of Hope’ at Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre, Gisozi by President Paul Kagame, which will burn for the 100 days. The President is also expected to lay a wreath in honour of not only the 250,000 victims interred at the memorial, but also all victims of the Genocide. Later, a minute of silence will be observed countrywide.

Kagame has been president of Rwanda since 2000 and has faced widespread accusations of abusing the memory of the genocide to silence political opponents. The latest U.S. State Department human rights report on Rwanda, published in March, accused the government of “unlawful or arbitrary killings; torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by the government … [and] serious restrictions on free expression and media, including threats of violence against journalists, unjustified arrests or prosecutions of journalists, and censorship.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.