The three leading contenders for the GOP nomination–Donald Trump, Sen. Ted Cruz, and Sen. Marco Rubio–all appeal to different segments of self-described evangelicals, a key group whose voting behavior will have a significant impact on the outcome of the Super Tuesday “SEC Primary” results.

Pollsters looking at the 2016 Republican Presidential primaries have created confusion around the voting behavior of self-described evangelical Christians by failing to properly define the term.

Most exit polls heighten that confusion by failing to ask more than a single cursory question of voters: in some polls it’s “Are you a born-again Christian?,” in others it’s “Do you consider yourself to be an evangelical Christian?”

As Nicolle Russell wrote recently at the Federalist:

The term evangelical is a broad one, and has grown more so over the last decade, at least to the media and those who remain unaffiliated with religious groups. That means the actual number of those who would identify themselves as evangelical (over another denomination or sect) is small but the media remains rather annoyingly unaware of this. So in an exit poll, rather than asking if an individual is Orthodox, Catholic, Jewish, Lutheran, or evangelical, they ask the latter.

It’s somewhat like asking people if they all like dessert, and when 72 percent said yes, pollsters exclaim that everyone loves chocolate! Kind of, but not exactly, and the distinction matters because evangelicals are known for toeing a certain conservative party line.

Two recent Breitbart focus groups of evangelical Christians who intend to vote in Tuesday’s GOP primary in Tennessee, the statements of the campaigns themselves, the limited political polling data available, and academic literature on the definition and behavior of evangelical Christians suggest that rather than behaving as a single monolithic group, evangelical voting behavior can best be understood by looking at two distinct types of “self-described evangelicals,” each of which is further divided generationally.

For “traditional” or “committed” evangelicals, their Christian faith is the defining element of their lives, and is expressed in a number of observable behaviors: weekly attendance at church services, weekly attendance at church classes, participation in small Bible study groups, regular prayer, frequent reading of the Bible, participating in musical worship, listening to Christian music, charitable giving—often tithing to their church, and participation in charitable acts.

Committed evangelicals are likely to subject every action they undertake in life based on its consistency with Christian principles.

For “cultural” evangelicals, their faith is an important, but not necessarily defining, element of their lives. It is often accompanied by behavior that differs from “committed” evangelicals. They may or may not regularly attend weekly church services. Beyond that, how they express their faith behaviorally appears to be unique to each individual.

Anthony Bradley, associate professor of religious studies at King’s College, a Christian college based in New York City, recently told the Christian Post:

Trump evangelicals are evangelicals who have been on the margins. They are not mainstream evangelicals who are burdened by the sort of traditional concerns of the church. Trump evangelicals are angry. They are mad at the Obama administration. They believe that the Obama administration has ruined the country.

Though academics have not unified around a single definition of “evangelical,” in our previous reporting , Breitbart News offered this definition of an evangelical Christian based on the work of historian David Bebbington:

Someone who is born again in Christ (conversionism), has a personal relationship with Jesus who died for our sins (crucicentrism), believes the Bible is the inerrant word of God (Biblicism) and has a duty to spread the good news of Jesus to non-believers (activism).

“Committed” evangelicals absolutely affirm these four elements of belief. “Cultural” evangelicals may affirm them as well, but perhaps not with the level of intensity found among “committed” evangelicals.

Within each group, there is also a generational divide. Self-described evangelicals over the age of 35 differ from those 35 and under with regards to their views on the sovereignty of the United States.

The 26 participants in two focus groups of committed evangelical Christians who intend to vote in the March 1 Tennessee GOP primary conducted by Breitbart News in Nashville, Tennessee on February 25 affirmed this definition of what it means to be an evangelical Christian.

“For me, being an evangelical Christian means you put God in the center of everything you do. You business, your family, how you vote, how you get involved in political circles,” a man in his fifties who participated in the focus groups said.

Politics is dirty, he added, but said, “to me, being an evangelical Christian means getting back involved in that process.”

“I’m a theology student at [a Christian university],” Brandi, a 34-year-old mother said, “so we need to know the definition of evangelical. The root world comes from a Greek word… meaning the good news or the message, so to be evangelical means to share the good news [of the Gospel]. So that’s what we do.”

“To be an evangelical Christian, I think you must be born-again in Christ,” Don, a retired manager of a non-profit in his sixties added. “A lot of people misinterpret the meaning of Christian. If you walk down the main street in Nashville, 90 percent of the people are Christian, but you ask them what it means to be a Christian, 85 percent of them don’t know,” he said.

“One step further,” a business man in his forties added. “You’ve got to believe it. You’ve got to read the scriptures. That becomes the core of the decisions you make [about your business and personal life], being morals based rather than values based.”

“To me, every breathing moment is focused on my relationship with God and what I do with that time,” another business man in his forties added.

The generational divide among committed evangelical Christians was apparent in the Breitbart focus groups. It revolved around the answers to this question: “Is America a Christian Nation?”

The assertion that this question marked the generational divide among evangelical Christians was first made by Jon Ward of Yahoo News in an article that quoted Eric Teetsel, Marco Rubio’s director of faith outreach, extensively.

But if you want to know whether an evangelical Christian — in Iowa or beyond — is supporting Cruz or Rubio, ask them one simple question: Is America a Christian nation? Most Cruz supporters would answer yes unequivocally. But if they pause before answering, it probably doesn’t matter what they say after that. You’ve more than likely found a Rubio voter.

Here’s the rub: the kind of evangelical who pauses when asked the “Christian nation” question – the Rubio type – is most likely to be under 45 and less politically active than the Cruz evangelical.

That assertion was backed up in the Breitbart focus groups of committed evangelicals, though the age cutoff for differing views was lower—35 rather than 45.

When focus group participants were asked “What is meant when we say America is a Christian nation?”, sparks flew.

“It was founded on Godly principles,” a woman in her fifties said quickly.

“I’ve got to disagree,” 34-year-old Brandi jumped in.

“There’s no mention of God anywhere in the Constitution, and half of the Founding Fathers were Deists,” she continued, amidst cries of “That’s not true!” from the other participants.

“I don’t like it, I don’t like it at all,” said Brandi, “because I was raised on the principle that this is a Christian nation, and we’ve gone away from it,” she added.

“But we’re having to take a course on Religion and American culture [at the Christian university where I’m pursuing a degree in theology] and so we’ve gone back to the very beginning and the other day we had to break everything apart and look what’s really going on in our Constitution, but we were not founded on Christianity,” Brandi said.

“Some of them were Christians, but the majority [of the Founding Fathers] were Deists. But the whole point of the Constitution and the building of the United States was religious freedom because they wanted to be out from under the umbrella of the Roman Catholic Church.”

“As far as our written documents being based on the Christian faith, it’s just not there,” she concluded.

“The Founders purposely avoided the reference to scripture, but what they derived from scripture was the principles scriptures supported, which allowed for the freedom of religion,” a man in his fifties countered.

“The Founders knew you could not create a state religion,” he added.

“Our founding document was the Declaration of Independence,” another man in his forties countered, “and it talks about God endowing us with unalienable rights.”

“When you look at our early American history, you can’t just look at the Constitution, you have to look at the lives of men like John Adams, who said the American government will not succeed unless it’s a Christian nation,” another man said.

“You have to go beyond the written document to look at the basis upon which they wrote the documents. The most quoted source in all of the meetings surrounding the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution was the Bible. The second most quoted source was the 1643 Westminister Confession of Faith.”

“Congress, when they authorized the appropriations of funds for the first Treasury Building specifically instructed they be required for use as houses of worship. Congress authorized the purchase of Bibles so that every student could have a Bible.”

“Our Founding Fathers knew that citizens whose hearts were rooted in Christian principles were necessary for the survival of the government, and the lack of that is what we’re seeing as the root of our troubles today.”

“When we separated from the prevailing thought was Christianity. That was our point of reference. If you were to ask George Washington or John Adams if they set out to create a Christian nation I think they would say, no, because we always were a Christian nation,” Don, in his sixties said.

“I have these primers from the early 1800s, and it’s all based on Christian religion, things out of the Bible,” Debbie, a woman in her fifties, said.

“What you’re being taught in school now,” she said to Brandi, “is a little bit of revisionism.”

“I bought some history textbooks that were printed in the 1960s when I was on vacation a few years ago. There’s just not a lot of similarity between what they were teaching students in the 1960s to what they’re teaching now,” Debbie added.

Half of the focus groups agreed while half disagreed that the United States is still a Christian nation.

“I think it is,” said one woman in her fifties.

“It has the potential to be,” Eric, a business executive in his sixties said.

“What we’ve done as a culture, as a society, is abandon principles which are based on scripture,” he added.

“To me, we are a Christian people, but we have drifted from it, and our leaders have walked away from it,” a man in his fifties said.

“People have been shamed into keeping their mouths shut,” a man in his forties said. “I think there’s a re-awakening that’s starting to happen. People have had absolutely enough,” he added.

Those different view points among evangelicals are likely to flow from the answer to this one question: “Is the United States a Christian nation?”

A significant number of evangelicals 35 and under believe the United States was never a Christian nation and is not now a Christian nation.

In contrast, evangelicals over the age of 35 are virtually unanimous in their opinion that the United States at its founding was a Christian nation, though it is currently in danger—on the precipice even—of becoming “not a Christian nation.”

Despite caricatures in the press that committed evangelicals are yearning for the establishment of a Christian theocracy, the Breitbart focus groups demonstrated that they have a clear understanding that “the separation of church and state” in the United States means simply that “Congress shall make no law regarding the establishment of a religion,” as the First Amendment to the Constitution states.

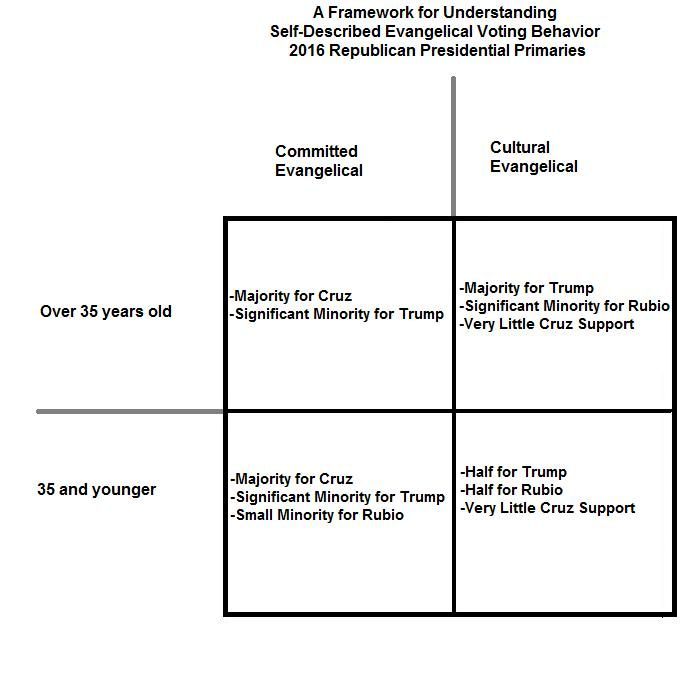

One possible framework evangelical voting behavior in the 2016 Republican Presidential primaries, based not on hard polling data (because there is none), but on the various objective and subjective available data, that may help explain the election results to date in Iowa, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Nevada is shown below: There is no data which shows what percentage of self-described evangelicals are in the “committed” group and what percentage are in the “cultural” group.

There is no data which shows what percentage of self-described evangelicals are in the “committed” group and what percentage are in the “cultural” group.

We do know that in the overall population, Pew Research reports that 25 percent of the population self-describes as “evangelical.”

It is probably safe to assume that at least half of these self-described evangelicals fit in the “committed” group, though that percentage is likely to vary dramatically by region of the country.

How can this framework help us understand evangelical voting behavior to date and can it at all be predictive of voting behavior on Super Tuesday, the SEC Primary, and beyond?

Let’s begin with the three completed electoral contests in which we have some data:

- 64 percent of GOP caucus attendees in Iowa were self-described evangelicals, according to entrance and exit polls (as opposed to 28 percent of the Hawkeye State’s general population). Cruz won self-described evangelicals, garnering 34 percent of the vote, to Trump’s 22 percent and Rubio’s 21 percent.

- 20 percent of GOP primary voters in New Hampshire were self-described evangelicals, according to entrance and exit polls (as opposed to 13 percent of the state’s general population). Trump won a plurality of the self-described evangelical vote over Cruz and Rubio.

- 70 percent of GOP primary voters in South Carolina were self-described evangelicals, according to entrance and exit polls (as opposed to 35 percent of the state’s general population). Trump won a plurality of the self-described evangelical vote over Cruz and Rubio.

The framework of evangelical Christian voting behavior in the 2016 Republican Presidential primaries, which is admittedly based on sparse polling data and draws on qualitative focus group results and anecdotal observations, suggests:

- Committed evangelicals over 35 support Cruz in the majority and Trump in the minority.

- Committed evangelicals under 35 have similar patterns but Rubio gets some support.

- Cultural evangelicals over 35 heavily support Trump, but don’t like Cruz’s “preacher-like” style or alleged dirty tricks.

- Cultural evangelicals under 35 split between Trump and Rubio, and particularly don’t like Cruz’s “preacher-like” style or alleged dirty tricks.

There is no specific polling data to support the assertion set forward in this framework that Cruz has little support among cultural evangelicals. That is, however, in essence the argument that Cruz’s father, pastor Rafael Cruz, made recently in an appearance on Iowa-based syndicated radio host Steve Deace’s program when asked about Donald Trump’s plurality victory among self-described evangelicals in the South Carolina GOP primary:

Well, I think that they’re defining evangelicals in a very loose manner . . .If we look at the numbers, those that are people that call themselves born-again Christians that are committed to the lord, we won overwhelmingly among that group. Unfortunately — and this is a message that I have been carrying to America, as you said, for several years — there are too many people in the church that have actually become lax about the word of God, that they are being more concerned with being politically correct than being biblically correct, they have diluted the word of God in order to be palatable to everyone.

In states where committed evangelicals have a disproportionately higher turnout rate, like Iowa, Ted Cruz does well. But because Ted Cruz’s support among evangelicals is limited to “committed” evangelicals—cultural evangelicals do not appear to be warming to his message—he has a ceiling defined by the turnout of “committed” evangelicals.

In states where there is an equal or higher turnout of “cultural evangelicals” –like New Hampshire and South Carolina, he does less well.

A cursory look at the percentage of each SEC primary state’s population that self-describes as evangelical might suggest Ted Cruz would have a good chance of electoral success on Tuesday. That, however, is misleading, because in those very states, there is a high proportion of “cultural evangelicals.”

As Emily Cope and Jeffrey Ringer wrote in the 2014 book, Mapping Christian Rhetorics:

Because evangelical Christianity is normative in the Southeastern U.S., where the Southern Baptist Convention exerts outsized cultural influence, traditional measures of piety aren’t useful for identifying individuals who enact evangelical discourse.

In other words, the percentage of self-described evangelicals in Iowa who are cultural evangelicals is likely to be quite low, while the percentage of self-described evangelicals in South Carolina and other Southeastern states who are cultural evangelicals is likely to be much higher.

This suggests that in those states where Cruz can mobilize “committed evangelicals” he may do well on Super Tuesday among self-described evangelicals. In states, where he cannot, however, Trump and Rubio are likely to do better among self-described evangelicals.

Of the seven Southern states (out of a total of twelve in play) on Super Tuesday, the demographics look more like South Carolina(35 percent evangelical) than Iowa (28 percent) in Georgia (where 38 percent of the population is evangelical Protestant, according the recent Pew Forum study of the Religious Landscape of America), Arkansas (46 percent), Oklahoma (47 percent), and Tennessee (52 percent).

Though the portion of Virginia’s population that is evangelical (30 percent), is very close to Iowa’s 28 percent, the state demographically looks very little like Iowa, and Cruz has nothing near the “committed evangelical” infrastructure he had in Iowa.

Only in his home state of Texas (with 31 percent evangelicals) are there similarities to Iowa. Many of the ground game canvassers who powered his Iowa victory traveled up from Texas, and they are likely to duplicate that effort on his behalf in the Lone Star State on Tuesday.

Barring an unforeseen development, while Cruz is poised to win self-described evangelicals in Texas on Tuesday, duplicating that feat in other Southern states is a challenge that will turn on the degree to which he’s been able to mobilize those states “committed evangelicals.”

Trump has the advantage of appealing to all four segments identified in the Breitbart Framework for Understanding Self-Described Evangelical Voting Behavior, while Rubio is fighting tooth and nail with Trump to gain support from the two segments of self-described evangelicals that comprise “cultural evangelicals.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.