Can American public life get any crazier? Get any more circus-like? Any more gladiatorial combat-like? It seems that all we see and read about these days are accusations, investigations, confrontations—and, as Brett Kavanaugh put it, “character assassinations.”

Welcome to the Jungle

Indeed, the fight over Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination provides a snapshot of the national maelstrom. As Kavanaugh said in his September 28 hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, “This has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit . . . My family and my name have been totally and permanently destroyed . . . This confirmation process has become a national disgrace.”

Perhaps most memorably, directing his fury at Senate Democrats, the D.C. Court of Appeals judge added, “You have replaced ‘advise and consent’ with search and destroy.”

One of the Republicans on the Judiciary Committee, Sen. Lindsey Graham, notably echoed Kavanaugh’s attack on the Democrats, describing their last-minute leak-and-ambush tactics as “the most unethical sham since I’ve been in politics.” Sen. Ted Cruz agreed with Graham, labeling the Kavanaugh hearings as “one of the most famous shameful incidents in the history of the U.S. Senate.”

To be sure, the Senate Democrats—including, of course, the weirdly gladiator-minded Senator Spartacus–were bloody mad, too, albeit perhaps because their familiar “borking” tactic wasn’t working as well as they’d hoped.

Yes, the anger on both sides of the aisle was obvious. As a New York Times reporter tweeted: “What I saw today was a fury between members of opposite parties that is as profound and unnerving as I’ve ever seen. They’re not faking it.”

In the meantime, out in the liberal grassroots, the anger was even more obvious—or egregious: Jill Filipovic, a “scholar” at a D.C. think-tank, tweeted, “Divorce your Republican husbands.” And the actress Mira Sorvino called for “revolution.” In other words, pretty much the usual.

For his part, MSNBC anchor Chris Hayes took a more sober tone: “A legitimacy crisis is unfolding before us and it’s only a question of when the cataclysmic moment comes when no one can deny it anymore.”

We needn’t agree with Hayes on much of anything to still be struck by his dire words, “cataclysmic moment,” and political science-y jargon, “legitimacy crisis.” A legitimacy crisis comes when people lose faith in the political system. And there’s a lot of lost faith going around, for myriad reasons, including—just to name a very few—the Iraq War, the Wall Street bailout, and the doings of the Deep State.

Of course, the ultimate consequences can be, yes, cataclysmic. Indeed, amidst all the talk of “coarsened culture” and “partisan polarization,” one even hears talk, from serious people, about a possible civil war. Thus we are reminded of Abraham Lincoln’s declaration of June 16, 1858: “A house divided against itself cannot stand.” And we all know what happened less than three years later.

Yet if the Civil War is a common historical reference point for Americans, as they look to the past for clues about the future, it is not the most apt reference point. Why? Because the Civil War was mostly touched off by slavery, and that’s long gone. And yet the absence of slavery doesn’t mean that there aren’t plenty of other potential flashpoints. Indeed, if we look back at history, we can learn some sobering lessons as to how societies can unravel.

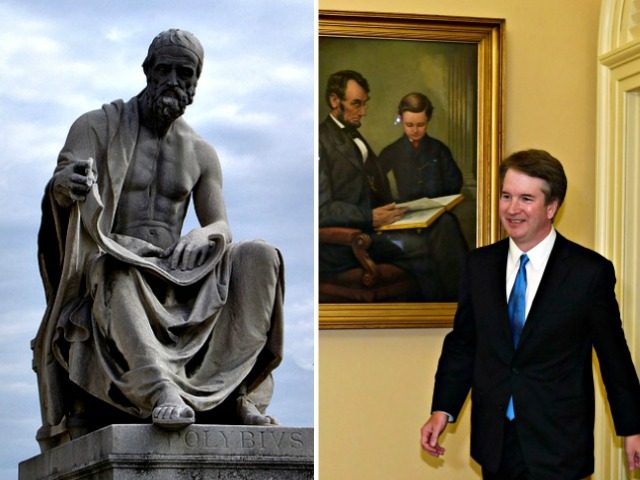

Gloomy Wisdom from a Greek

In particular, we might look to the Greek historian Polybius. He can’t directly address the current state of affairs, since he died in 118 B.C., and yet his wisdom still speaks to us, loud and clear. In fact, his analysis of political events during polarizing times is timeless.

One of his key themes was the way in which societies transition from one system to another. For instance, how is it that a democratic system falls apart, to be replaced by another kind of system—a worse system?

Mindful of the history of the ancient Greek and Roman republics, Polybius observed that a successful democracy had to observe certain groundrules to guide popular participation. That is, a democracy had to be more than just majority rule; if it was just that, it would prove to be unstable and short-lived. In his view, simple majoritarianism wasn’t democracy at all; it was, instead, to use another Greek word, an ochlocracy. That is, mob rule. (Interestingly, the Latin translation of “ochlocracy” was mobile vulgus, from which we get the word “mob.”)

This distinction, between democracy and mob rule, is critical. In The Histories, Polybius noted, “It is not enough to constitute a democracy that the whole crowd of citizens should have the right to do whatever they wish or propose.” Instead, he argues, a successful democracy requires “traditional and habitual” virtues of self-restraint, including “reverence to the gods, succour of parents, respect to elders, obedience to laws.” Only in such a disciplined context, he continued, can majority rule succeed. Indeed, only then “we may speak of the form of government as a democracy.”

In other words, for a democracy to flourish, certain preconditions have to be met, including a basic cultural commitment to deliberation and restraint. If this sounds “conservative” to the modern ear, well, so be it, although we can note that Polybius mades no prescription as to, say, tax rates, trade laws, or foreign policy. He was simply laying down the societal predicates for an effective democracy. And if that sounds conservative, well, it’s the conservatism of prudence and moderation, not conservatism bound to any larger ideology.

Importantly, the American Founders agreed with Polybius; indeed, they specifically relied on him as an intellectual guide. For instance, James Madison, author of the U.S. Constitution, cited Polybius in a letter to Thomas Jefferson in 1787, and again in Number 63 of the Federalist Papers, published the following year. (The Federalist Papers, of course, were the articles and pamphlets written in support of the ratification of the Constitution.)

Indeed, it’s fair to assert that much of the argument over the Constitution was framed in Polybian terms—that is, how to keep a democracy from degenerating into a mob-ocracy, and from there, into anarchy and debacle.

In the 18th century, the common word for “mob” was “faction.” And it was faction, and factionalism, that the Founders feared the most. And so factionalism was very much on the mind of Madison as he authored the Constitution, a document outlining a rules-based democracy. Such rules are vital, Madison wrote in Federalist Number 10, because “a pure democracy . . . can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction.” Continuing in that vein, Madison warned that factionalism was, inevitably, a formula for civil war: “The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame.”

And so, he continues, absent proper constitutional restraints, once the majority gets up a head of steam, “there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party.” Unchecked mobs? Demanding violent sacrifices? That’s indeed the stuff of lynchings, even open combat.

Madison’s antidote to the “mischiefs of faction” was, again, the Constitution, with its carefully calibrated enumeration of powers, spread across three branches of government—executive, legislative, and judicial. In other words, Madison’s vision was of a republic, not a pure democracy, or, as some might call it, a democratic republic. Yet by any name, Madison’s goal was clear: to compartmentalize popular passions and thereby protect the United States. Revealingly, the title Madison gave to Federalist #10 was, “The Utility of the Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection.”

Madison knew that two millennia earlier, Polybius had written about what happens when faction and insurrection run amok: “The mob . . . as soon as it has got a leader sufficiently ambitious and daring . . . produces a reign of mere violence.”

To be sure, today we aren’t living under a “reign of mere violence”—although House Majority Steve Scalise would have good reason to differ. Yet still, we might look around and ask: How far away are we from a mob-ridden dystopia? Without a doubt, we already have plenty of psychic violence—we saw a lot of it last week, and not just on Capitol Hill.

For instance, Lauren Baer, the Democratic nominee for Congress in Florida’s 18th Congressional district, spoke on behalf of mob “values” when she said, “I stand in solidarity with women and men who share their stories. Every single allegation of sexual assault and sexual harassment should be heard and believed.” [emphasis added] To which the rest of us might say, Quick! Someone get Ms. Baer a copy of the classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, which is, of course, all about a false rape accusation. In the meantime, Brett Kavanaugh must know what it’s like to be the subject of Baer-type frenzy.

As Polybius writes, when democracy has yielded to mob rule, it’s all downhill: “Then come tumultuous assemblies, massacres, banishments, redivisions of land.”

And yet here’s where Polybius gets even more interesting. As he puts it, just at the moment when the formerly democratic society is “losing all trace of civilization,” the trend-line changes. But it changes, he adds, not back to democracy, but rather, toward tyranny; the mob “has once more found a master and a despot.” In a grim way, this all makes sense: Ordinary people don’t want to live in chaos; in the face of unchecked violence and banditry, just about any kind of order is preferable. And that preference opens the door to tyranny, which may be popular—even very popular—at least for a time.

Thus we see the heart of Polybius’ argument: If it’s not properly tended, a democracy devolves into mob-ocracy, which then gives way to tyranny.

The Modern Polybius

By now, some will have noted that Polybius’ grim historical sequence has a familiar ring. Indeed, all over the Internet one sees words of warning, attributed to the Scots historian Alexander Fraser Tytler:

The average age of the world’s greatest civilizations from the beginning of history has been about 200 years. During those 200 years, these nations always progressed through the following sequence: From bondage to spiritual faith; From spiritual faith to great courage; From courage to liberty; From liberty to abundance; From abundance to selfishness; From selfishness to complacency; From complacency to apathy; From apathy to dependence; From dependence back into bondage.

In point of fact, Tytler never said exactly this, although he expressed similar sentiments in an 1801 volume that frequently cited, yes, Polybius. Actually, though, the above words come from an American businessman, Henning Prentis, writing in the 1940s.

Yet there’s not much point in getting bogged down over exact authorship. Indeed, Polybius deliberately wrote in such a way that any thoughtful observer, in any era, could apply his wisdom:

If a man have a clear grasp of these principles he may perhaps make a mistake as to the dates at which this or that will happen to a particular constitution; but he will rarely be entirely mistaken as to the stage of growth or decay at which it has arrived, or as to the point at which it will undergo some revolutionary change.

What matters—whether the wisdom comes from Polybius, Tytler, Prentis, or anyone else today—is that we grasp the moral of the history: We must not let democracy degenerate into chaos, because if we do, the result won’t just be more chaos but, rather, tyranny.

As we have seen, that’s exactly the fate that Madison and the Founders wished to avoid. Now, today, in our time, we’re on notice: If we don’t reverse the path to chaos, the American republic, too, will be entered into the annals of history as just another sad failure.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.