CARACAS – Venezuela has always had trouble maintaining a functional power grid. I lived in the city of Punto Fijo from 1992 to 1996, blackouts were occasional back then. But those woes of times past are nothing compared to the catastrophic collapse of our power grid that started almost a decade ago.

Twenty years of Bolivarian Revolution bought about glaring mismanagement and underinvestment in our power grid. Our electric sector was nationalized in 2007, which – you guessed it – is when the power tribulations truly began to plague Venezuelans.

Experts have warned for years of the imminent collapse. Some states, such as Zulia, my birth state, have been suffering a gruesome power rationing for years.

The much-anticipated collapse finally happened on March 7, 2019.

The entire country was thrown into the Middle Ages in a snap. I went thirty hours without power. It returned to my area for approximately twelve hours. Then I was met with another thirty-hour blackout.

As expected, Maduro blamed the incident on America. He hasn’t offered an official explanation beyond stating that it was an “Electronic coup” and a “cyber attack.”

Caracas felt like a ghost town. You couldn’t hear a single thing, not even gunfire and car alarms — quintessential sounds that one often hears through the night. It was as if we were all collectively going through a bizarre mass solitary confinement.

Water distribution was disrupted, people desperately sought for it, even in sewer drains. Telecommunications, as well – we were essentially disconnected from the world. We couldn’t even access our money since the banking network was offline. In Zulia, all hell broke loose.

After the longest blackout in Venezuelan history, power continues to be erratic. The power had scarcely recovered before a second series of long blackouts hit the country towards the end of March. Power, internet, and cellphone reception continue to be unstable. The blackouts and brownouts are constantly interrupting my ability to write this article right now.

If you’re curious, here’s the convoluted power rationing schedule. Caracas was exempt from rationing due to “military demands.”

This new calamity that has befallen us is far from over. Maduro recently announced that power will be rationed for thirty days. Judging by past experiences, this 30-day plan will likely morph into 60, then 90, then 120.

I might as well get ready for it to become a quasi-permanent reality, like the water rationing that we’re still going through.

For the longest time, Caracas had to deal with neither power blackouts nor water shortages, its prerogative as the nation’s seat of power. It has now been over three years since we had running water 24/7.

People draw water from a spring water tank to be used in their toilets, at Petare neighborhood in Caracas on April 1, 2019. (FEDERICO PARRA/AFP via Getty Images)

The government attributed the initial rationing to a draught period that has long passed, a weak attempt to mask a service clearly in a shoddy state of management and disrepair. Like everything else, even the lies produced by socialism are low-quality. As for the quality of the water (when it does finally appear!), that leaves much to be desired as well, which is why I always implore people that if they have to visit Venezuela, they shouldn’t drink tap water under any circumstances.

Like the power failures, instead of fixing the water distribution problems, the regime came up with an overly complicated water ration schedule, so complex that they don’t even follow it themselves.

According to that schedule, we should get water five days a week, some days during the morning, others during the night. Want to take bets on whether that’s true?

For the past three years, the area I live in only gets running water from Wednesday evening until early Sunday morning; sometimes it doesn’t arrive until Thursday or even Friday, but you can surely be certain that it’ll be gone before noon on Sunday.

The rest of the days we go by the building’s small water tank. It’s not a large one so we have to use it sparingly: only two hours per day. My biological clock is now based around our water rations.

I need to be ready before 8 p.m. because that’s when we have exactly one hour to use the toilet, shower, refill buckets, and do dishes.

There have been several times when we’ve run out of water. When that happens, we have to rely on the even smaller tank that’s meant for fire emergencies.

A knack for puzzle-solving and boundless creativity are invaluable perks in my limited skillset arsenal, perks that I’ve had to constantly employ to survive in whatever is left of this country. One of my ‘intelligent’ solutions to our water woes involves placing a bucket at the end of my air conditioner’s water pipe, slowly filling it overnight until – voilà! — an extra toilet flush that refills itself.

Following the severe shortages that started in March 2019, I’ve extended this wonder of Venezuelan engineering to the second air conditioner in our house, so now there are two buckets: up to four self-refilling toilet flushes now!

If three years of rigorous water rationing wasn’t enough, the collapse of our power grid made it all worse.

I am writing this paragraph amidst a widespread water shortage. The nation’s water pumps can’t function without power, and they require lots of it. The constant blackouts have disrupted their startup process as well — which complicates things.

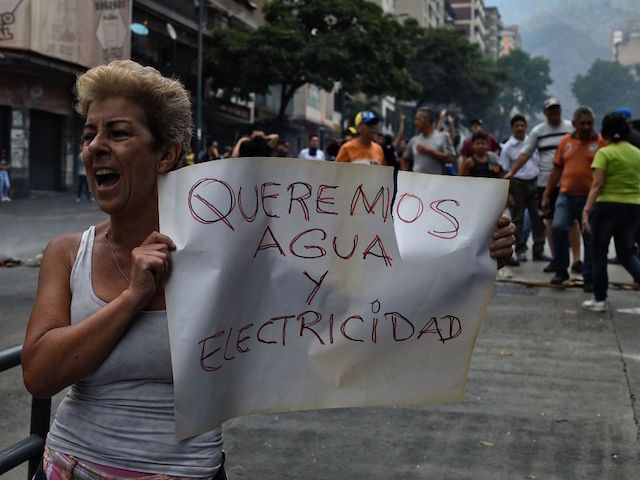

A woman holds a placard reading “We Want Water and Electricity” as she shouts slogans during a protest for the lack of water and electric service during a new power outage in Venezuela, at Fuerzas Armadas Avenue in Caracas on March 31, 2019. (FEDERICO PARRA/AFP via Getty Images)

We went from the early hours of March 24 to April 5 without water, stretching our reserves to the best of our ability. I never wanted a shower more badly than during those days.

The inevitable collapse of our power grid in March 2019 dialed the problems up to eleven and as a result, water distribution has been extremely erratic. Throughout the year, we’ve suffered through several days without water, sometimes over a week. Nowadays, we’re lucky if we get more than 36-48 hours of water per week. The excuses have been as absurd as it gets, from simple “low pressure issues” to “we haven’t been authorized to open the valves for that region yet.”

Power has become relatively stable in Caracas, with sporadic blackouts and fluctuations in power here and there – this is the capital, after all, the seat of power of this Socialist Revolution, and it must be kept afloat at all costs. Things are even direr and more inhumane outside this city’s borders; my father tells me that he only gets water for two days — every three months.

Daily blackouts that can last eighteen hours or more continue to plague other regions of the country with no end in sight. These public utilities woes have long since become part our daily bread and butter (well, it’s not like you can get those with ease every day here, but you get my point). It’s all been so tiresome and exasperating.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

This is the third in a series of articles on life in Venezuela. Begin the series here. Continue the series here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.