Democrats and Silicon Valley are locked in a head-on collision course; this week, New York City regulators proposed rules requiring Uber and other ride-hailing startups to get pre-approval each time they make major changes to their apps and pay $1,000 to cover the government’s labor costs. The battle between Uber and New York is a perfect example of the fundamental conflict between Democrats and Silicon Valley.

Generally speaking, Democratic regulators want Silicon Valley to exist in a permission-based world, where companies can prove no harm before launching products. Yet Silicon Valley’s approach to innovation has historically been to cobble together a bunch of rough ideas, test them in public, and see what does not fail.

Democrats prioritize predictable economic outcomes over potential unexpected innovation. The rest is explanation:

Do Democrats Really Want to Regulate Silicon Valley More Than Republicans?

Generally speaking, Democrats have been more regulation happy than Republicans against new tech companies. Democrats have been at the forefront of regulations over ride-hailing, championing the first rules in Washington, D.C., back in 2012, and most recently in Kansas and Las Vegas.

The same has been true for Airbnb, where Democratic leaders in San Francisco and New York have proposed tough restrictions on users wishing to rent out their homes.

Discretely, tech founders tell me that they loath moving into local markets with Democrat-controlled governments because it means they will have an uphill regulatory battle. Republican strategists commonly see the predictable regulatory issue as an opportunity to win back Democrat-heavy cities, where companies and consumers are frustrated with their liberal representatives.

But Don’t Republicans Demand Things of Tech Companies, Too?

Yep! Most notably, Republicans have taken the lead on some surveillance laws, creating and sustaining rules requiring backdoor access to tech company data for intelligence agencies investigating terrorist threats.

However, the Grand Old Party has been internally conflicted about any surveillance laws that create complicated logistical burdens on tech companies, such as when they blocked the Cybersecurity Act of 2012 over information-sharing requirements.

Either way, Republicans have rarely stopped tech companies from conducting business (notwithstanding the dubious constitutionality of mass surveillance). It has been the signature power move of Democrats to step in between tech companies and a product launch.

What Are the Implications of Permission-Based Regulation?

It slows down innovation more than a pie-eating contest before a marathon. Here are a few examples:

- Democratic regulators in the Security and Exchange Comission (SEC) have all but completely blocked crowdfunding investment, which was made legal by the JOBS Act three years ago. The SEC regulators worry that middle-class investors are not wise enough to invest in tech companies and have been searching for a way to minimize those who could lose their nest egg investing in risky tech companies.

- The public can no longer access most of 23andMe genetic diagnostic tests. The Food and Drug Administration stopped the direct-to-consumer genetics testing startup from displaying disease-related information because it was worried consumers were not knowledgable enough to make informed decisions. 23andMe is currently figuring out how to prove to the FDA that its genetic information does not cause consumers undo harm.

- Amazon would love to dispatch a drone to deliver Doritos to your doorstep during a 2 a.m. Star Wars marathon, but regulators are not sure how to make drones safe. As such, Amazon’s experiments in drone delivery technology have been hamstrung.

How Could This Impact the Price of My Uber?

Generally speaking, rapid permission-less innovation has been a key factor in cheap ride-hailing apps.

Currently, NYC is proposing that Uber, Lyft, and other ride-hail apps prove that drivers are safe and prices are transparent before they launch an app. Any change to the app that obscures this information will cost $1,000 in government approval man-hours. In other words, the city must approve changes to the app.

Imagining how startups could operate under these conditions is difficult. A mere few years ago, Uber was just expensive black car service. The cheaper UberX option was partly a response to Lyft, which had the original idea of allowing riders to tip drivers using their own cars (rather than a professional black car). It was possible to tip Lyft drivers absolutely nothing. Optional payments made Lyft wildly popular in San Francisco, inspiring Uber to popularize its own regular driver option, UberX.

Pricing is still evolving rapidly, with changes happening sometimes on a daily basis; in San Francisco, both Uber and Lyft are experimenting with carpooling options for as little as $5 for a ride across town. The chaotic competitiveness of Uber and Lyft has rapidly decreased prices, sometimes to the frustration of drivers who are now making less money.

NYC evidently wants to bring some order to the chaos, but it is difficult to imagine how Uber or Lyft could experiment so rapidly under new permission-based rules. That could mean more expensive options. Or, it may mean no features at all.

Just last month, Uber competitor Sidecar launched a program to deliver food. It had been stealthily testing this product for weeks. Could they have tested it in secret? Perhaps Sidecar would have needed to get permission through a public-approval process in NYC, so they probably would not have launched it there.

Permission-based regulation can delay innovation by months or years — far too long in the startup world.

I Thought Silicon Valley-Types Were Democrats. What Gives?

It’s a good question and one that deserves more investigating. We know that tech executives overwhelmingly funded Barack Obama in 2008 and that current San Francisco-based tech workers favor Hillary Clinton to libertarian icon Rand Paul by a whopping 50 points in the upcoming 2016 election.

I have written extensively about how Silicon Valley liberals seem quite different than their union-loving counterparts.

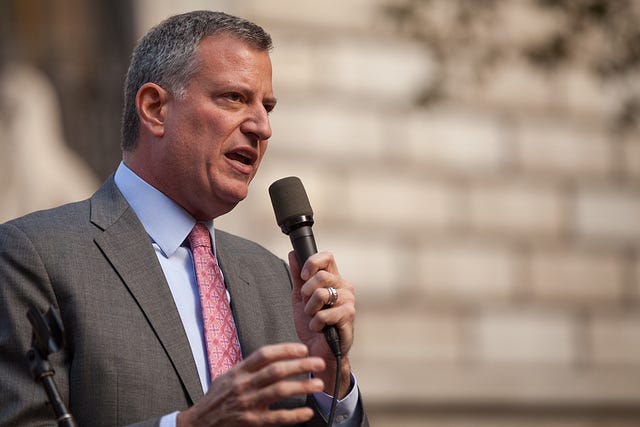

Traditional Democrats, like NYC Mayor Bill De Blasio, see the role of government as protecting consumers from unfair and unpredictable market forces. It is why two years ago, I predicted that he would be generally anti-startup, especially regarding companies like Uber.

Yet there seems to be a growing faction of Democrats, strongly linked to Silicon Valley and often mistaken as libertarians, who see the government as an investor in capitalism: they favor government-funded research, expansive free trade agreements, and near limitless high-skilled immigration — often in opposition protests within their own party.

It is important to know more about these competing visions of liberalism, which is why I am currently conducting psychological surveys to understand the differences. Readers can help me by taking a survey here.

However unique Silicon Valley liberals are, it does seem that agency regulators overwhelmingly come from the traditional Democrat circles. Silicon Valley’s embrace of innovative chaos is directly at odds with the economic predictability Democrats like to promise their constituents.

As much as tech workers currently like Obama and Clinton, these burdensome rules may test their loyalty to the Democratic Party— with big implications for the upcoming election.

The Ferenstein Wire is a syndicated news service. For inquires, email the editor at greg at greg ferenstein dot com.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.