On March 6, 1985, a stick of Kid Dynamite was tossed into the professional boxing ring at the Empire State Plaza Convention Center in Albany, New York. Less than two minutes into the first round, referee Luis Rivera mercifully stopped the fight. A short, squatty teenage heavyweight had just won his pro debut, destroying a stiff named Hector Mercedes.

Boom.

Thirty years later, the explosion still reverberates—and boxing has never been the same.

If you missed the early years of Michael Gerard Tyson, you missed something extraordinarily special. His squeaky, high-pitched lisp, all-black trunks, and malevolent malapropisms have been so shabbily parodied by sketch comedy shows, sports-wannabes, and even cartoon characters (Drederick Tatum of The Simpsons comes to mind), that Mike has mostly lost his menace.

It wasn’t always this way.

Think back to 1985: This was the height of the Reagan years—well before the advent of the UFC, submission holds, cage fighting and Mixed Martial Arts. If you were to mention “BJJ” to an ‘80s-era fight fan, he’d have assumed you were propositioning him and had a stutter. Maybe once a year, an atypically-transcendent title fight would air on closed-circuit television, mostly in big-city theaters, but the economics of professional sports was entirely different: pay-per view had yet to become the lynchpin of the prize-fighting profit-model. Instead, title fights appeared on some newfangled channel called HBO, and champions fought regularly on (gasp!) ordinary network television. And champions fought every few months: Larry Holmes defended his title 13 times from 1980 to 1983, and all of his title defenses took place in the United States.

Today? Since winning The Ring heavyweight title in 2009, Wladimir Klitschko has fought 10 times in roughly six years, and none of these 10 title defenses came in the United States. (Klitschko will return to America for the first time since 2008 next month against Bryant Jennings.)

Back then, heavyweight boxing remained an all-American pastime, and the heavyweight champion was the biggest star in the galaxy—bigger than Hollywood, instantly iconic.

From “The Fight of the Century” (in which Frank Sinatra served as a ringside photographer) to “The Rumble in the Jungle” to “The Thrilla in Manila,” the 1970s played out as a golden age of heavyweight boxing, with legendary luminaries like Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman trading haymakers, insults, and knockouts. By the 1980s, Ali’s old sparring partner, “The Easton Assassin” Larry Holmes, had emerged atop the heavyweight landscape. An unusually well-skilled fighter with a smothering jab and a sturdy chin, Holmes fought as one of the finest boxers to ever walk the earth. But he certainly wasn’t one of the most charismatic.

Mad Magazine snickered that Holmes was black and completely colorless at the same time.

In 1985 and 1986, a past-his-prime Larry Holmes lost back-to-back title fights to Michael Spinks, a blown-up light heavyweight. “The Thrilla in Manila” it was not. All the while, the public clamored for the Next Big Thing.

Then came Mike Tyson.

Boom.

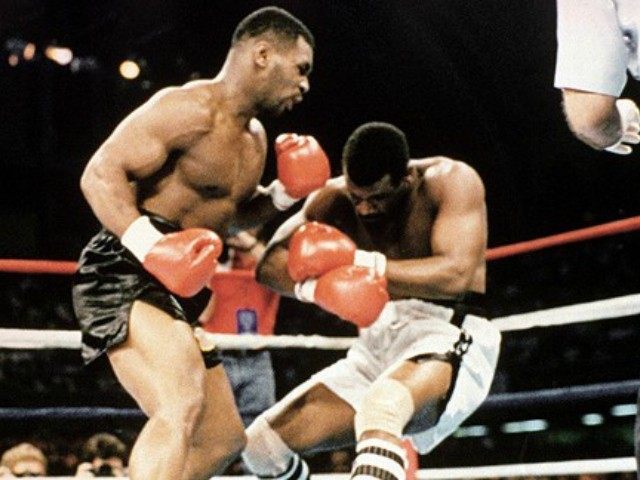

See, it wasn’t just that he was beating everyone; it was how he was beating everyone. Just 15 months after his professional debut, Tyson was matched against “Little Smoke” Marvis Frazier on national TV. The son of Joe Frazier, “Little Smoke” was a top-ranked amateur heavyweight, a National Golden Gloves Heavyweight Champion, and the National AAU Heavyweight Champion. Frazier entered the ring with far more experience than Tyson. He had a sterling amateur record of 56-2 and a pro record of 16-1. His only loss was to a prime Larry Holmes, and he had victories over accomplished heavyweights like James “Bonecrusher” Smith, Joe Bugner, and James “Quick” Tillis, as well as future cruiserweight world champion Bernard Benton.

Before anyone could blink, Tyson tore through the bottom of Frazier’s skull with a vicious, monstrous uppercut 15 seconds after the opening bell. With mind-blowing speed and the power of a freight train, Tyson proceeded to pound Frazier into an altered state of consciousness, leaving his helpless, lifeless carcass contorted in the corner. Referee Joe Cortez stopped the bout after only 30 seconds.

This wasn’t poetry. It was a massacre.

Boom.

And that was how Kid Dynamite fought.

After he KO’d Jesse Ferguson, the young warrior calmly told reporters: “I wanted to catch him right on the tip of the nose because I try to push the bone into the brain.”

He won his first 19 fights by knockout—12 in the first round.

At the tender age of 20, he became the youngest heavyweight champion in the history of the sport, annihilating WBC title-holder Trevor Berbick—a veteran, savvy fighter who had beaten Muhammad Ali, Pinklon Thomas, Greg Page, and John Tate, and had gone the distance against the great Larry Holmes.

Tyson KO’d him in the second round.

Referee Mills Lane remarked in amazement, “That left… so much controlled, sheer power, it’s amazing. For a moment I thought Berbick would stay up, then his eyeballs turned right up into his head.”

Tyson had his own take: “I was throwing hydrogen bombs. Every punch had murderous intentions.”

Boom.

A new champion was crowned. A new era in boxing had begun. But… something was not right.

“And if he’s lucky enough to kick my butt, I still won’t respect him. I think that in four or five years, he’ll be out of the picture. He’ll be in jail.”

Larry Holmes made that prediction on January 5, 1988. And 17 days later, Tyson put Holmes to sleep in the fourth round. (Holmes fought 75 times as a professional over an illustrious 29-year career, facing a slew of current or former world champions, including Muhammad Ali, Evander Holyfield, Ken Norton, Mike Weaver, Oliver McCall, Bonecrusher Smith, Tim Witherspoon, Leon Spinks, Mike Spinks, and more. Tyson is the only man to ever beat Holmes by knockout.)

Two months after flattening Holmes, Tyson stopped Tony Tubbs in two rounds. Three months later, he met the lineal heavyweight champion, Michael Spinks, in Atlantic City. It was the first time since “The Fight of the Century” that two undefeated heavyweight champions—each with a legitimate claim to the title—would meet in the ring. Tyson had the belts, but The Ring still recognized Spinks as heavyweight champion – the-man-who-beat-the-man-who-beat-the-man dating back to the retirement of Rocky Marciano in 1955.

“The Fight of the Century” took place on March 8, 1971. It was a riveting, emotional, 15-round performance. The 1980’s version would end in 91 seconds.

This was Tyson at the absolute pinnacle of his power. He stormed the ring, blasting his opponent as if his hands were comprised of sledgehammers. Spinks would never fight again.

Boom.

“I knew he couldn’t beat me,” Iron Mike boasted. “I knew he was too small. Those small guys, I eat them up. I knew I was gonna knock him out quick. I could smell fear.”

This was also the last time that Tyson would enter the ring with his long-time trainer, Kevin Rooney. One by one, the training and managerial team that was carefully put in place by his adoptive father, Cus D’Amato—the legendary boxing master who had taken Tyson under his wing since he was a young boy—was being systematically dismantled. More and more, promoter Don King was now at the forefront.

Everything started to unravel, including Iron Mike’s marriage to actress Robin Givens. Ten days after an utterly disastrous joint interview with Barbra Walters on ABC’s 20/20 (“Torture… pure hell… worse than anything I could possibly imagine,” she said of their marriage.), Tyson filed for divorce and an annulment. Not wanting to be maligned as a gold-digger, Givens said on October 20, 1988: “I unequivocally and irrevocably state as follows: (1) Michael can have his divorce. (2) I will not seek nor accept money for myself.”

Less than a month later, Robin Givens filed a $125 million libel suit against Tyson.

Boom.

Tyson’s reign of heavyweight tyranny would end in ignoble fashion on February 10, 1990, against James “Buster” Douglas. In the biggest upset in sports history, “The Baddest Man on the Planet” was knocked out in the tenth round. It was a stunning visual—big, bad Iron Mike crawling around on all fours, clumsily putting in his mouthguard backwards. But in retrospect, the writing was on the wall. Tyson’s use of the peek-a-boo boxing technique developed by Cus D’Amato had shown cracks two fights earlier against Frank Bruno; there were loud rumors of Tyson not taking his training seriously; and his sparring partner, Greg Page, had knocked him on his ass in a public pre-fight sparring session.

But things were about to get worse—much, much worse:

Exactly four years and 19 days after Mike Tyson brutally dispatched the Easton Assassin in the ring, Larry Holmes’ prediction came true: Tyson was convicted of raping 18-year-old beauty queen Desiree Washington.

He’d go to jail for three years. Kid Dynamite was now known as inmate number 922335. He’d return from prison, and regain the WBA and WBC titles. He’d chew through intimidated opponents such as Bruce Seldon, Buster Mathis, Jr. and Peter McNeely—as well as Evander Holyfield’s ears. He’d threaten to chew through Lennox Lewis’ (nonexistent) children. Alas, during this stage of Tyson’s career, when all was said and done, more was said than done.

Over his final 12 fights, Tyson had 5 wins, 5 losses and 2 no-contests. But he certainly did not “fade into Bolivian.”

Time is a funny, unpredictable thing. Back in the late 1980s, Mike Tyson was seen as a brooding, vulgar, unstable psychopath; Bill Cosby was a beloved role model and “America’s Dad.” Today, Tyson has successfully toured the country with his well-received one-man play, Mike Tyson: Undisputed Truth, and even stars in his own cartoon TV series, Mike Tyson Mysteries on Adult Swim… and Bill Cosby is an unemployable social pariah.

Nobody—and I mean nobody—could’ve planned for an outcome like this. But then again, as Tyson informed, “Everybody has a plan until they’re punched in the face.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.