Beneath the economic issues on the surface of the Pullman Strike that catalyzed the federal government recognizing Labor Day lay ugly racial resentments brushed aside in the intervening 123 years.

George Pullman famously hired African Americans to work for him. Eugene Debs infamously did not allow African Americans to join his union striking against Pullman’s company.

This complicates the prevailing narrative.

For instance, Bernie Sanders, who regards Debs as his hero, omitted the segregation of the American Railway Union he founded in the documentary Vermont’s junior senator produced about Debs in the late 1970s. “It is very probable, especially, if you are a young person, that you have never heard of Eugene Victor Debs,” the slide-showish video asserts. But one watching the documentary never learns that Debs refused to let blacks into his union. The Sanders documentary asks, “Why haven’t they told you about Gene Debs and the ideas that he fought for?”

One might pose a similar question to the senator: Why didn’t you tell us about Gene Debs’s racism?

“The American Railway Union was founded in the city of Chicago on June 20, 1893, by Eugene Debs and others who had been invited to participate in the movement,” informs historian Almont Lindsey, who, almost a half-century after the great unrest, authored The Pullman Strike: The Story of a Unique Experiment and a Great Labor Upheaval. “Membership was open to all white employees who served the railroads in any capacity, except superintendents and other high officials.”

Thomas Fleming, a railroad man who went on to a long and illustrious career in the African American press, reflected. “Pullman went on to become the largest single employer of blacks in America, and the job of Pullman porter was, for most of the 101-year history of the Pullman Company, one of the very best a black man could aspire to, in status and eventually in pay.”

Strangely, in our race-obsessed times, Pullman ranks as the villain and Debs the hero. In their times, the pair pitted against one another as a result of ugly issues of another kind. But race mattered as a subtext.

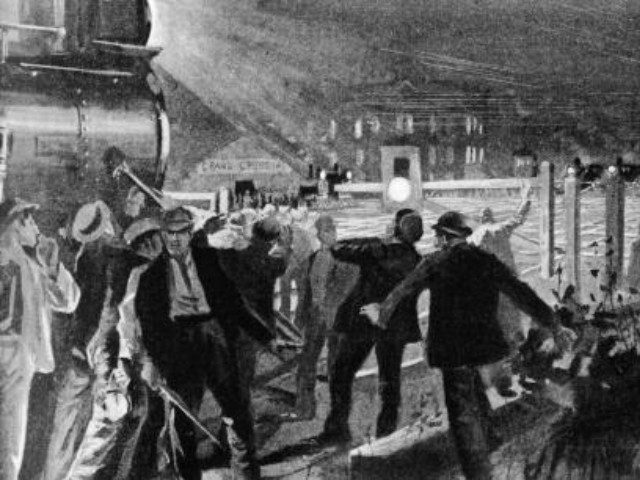

In 1893, a depression hit railroads hard, leading to the bankruptcy of the Philadelphia and Reading lines. Pullman slashed wages by about a fourth of their previous levels while not decreasing rents in his famous Illinois company town. This left workers understandably frustrated, and, in 1894, they went on strike, which, as the word indicates, involved violence.

Strikers cut telegraph wires, spread rails, and uncoupled locomotives from trailing cars to create runaway trains. In the Panhandle Yards in Chicago, arsonists set ablaze more than 700 railroad cars. In Sacramento, saboteurs killed three soldiers and a train engineer by removing spikes from rails and beams from a trestle bridge. In the Oklahoma territory, activists sawed away beams supporting a bridge and planted dynamite, which sent a speeding train plummeting. The unrest ultimately resulted in thirty deaths and $800 million in damages.

All this came about because the American Railway Union rejected George Pullman’s right to spend his company’s money the way he saw fit—just as they rejected his right to hire African Americans. When the feds grasped that the strike interfered with the delivery of the mail, the government intervened to end it. As a bone thrown to working men, Grover Cleveland’s second administration rushed to recognize Labor Day, whose existence as a local holiday here and there predated its national recognition.

If George Pullman sinned in giving his workers less, organized labor sinned more in blocking blacks from getting anything. The destruction of property to force a favorable end and the imposition of barriers to hiring African Americans may appear as very different tactics. But both strategies share the common denominator of manipulating the market to benefit one group at the expense of another.

Guilds protect insiders to the injury of outsiders. Blacks, the ultimate outsiders, suffered most as a result of the railroad unions that, in a very direct way, brought about Labor Day as a federal holiday. “Almost all of the major railroad unions banned African Americans from membership by constitutional provision,” George Mason University School of Law Professor David E. Bernstein writes in Only One Place of Redress: African Americans, Labor Regulations, & the Courts from Reconstruction to the New Deal. “African Americans were also banned from other unions that had large memberships among railroad workers, including the Boilermakers, the International Association of Machinists, and the Blacksmiths.”

The same restraint of trade the American Railway Union practiced during the Pullman Strike they embraced in excluding non-whites from the labor market.

Surely President Cleveland did not seek to honor the American Railway Union. His government jailed Eugene Debs, after all. But it’s difficult if not impossible to envision Labor Day becoming a national holiday at that time without the actions of the American Railway Union.

More than a century after the Pullman Strike, the origins of Labor Day, and the aims of the American Railway Union, remain obscured by time and hagiographic depictions of the group’s leader. In a race-obsessed age, this ignorance, willful or otherwise, strikes as strange. Those who put Eugene Debs on a pedestal tear down Christopher Columbus, George Washington, and Robert E. Lee from theirs. They all lived in another time but only some get judged by today’s standards.

The sins of some historical figures are more equal than those of others.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.