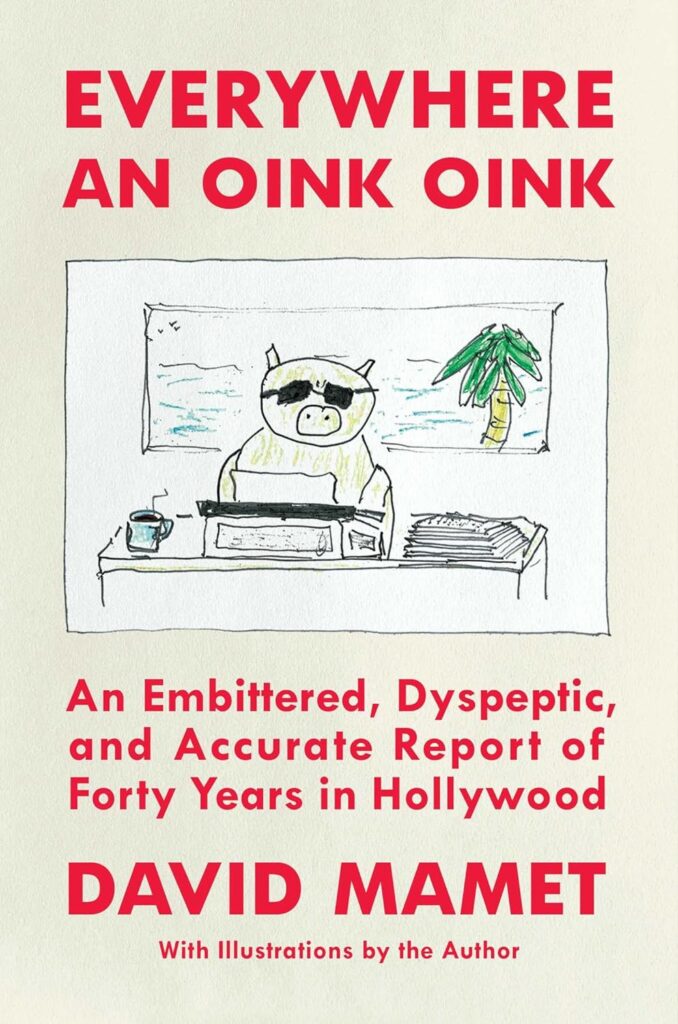

The full title of Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright David Mamet’s memoir is as follows: Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years In Hollywood. While I can’t speak to the book’s claim of accuracy, I can tell you it’s a smart, addictive, hilarious, and insightful look at everything from craven producers to the art of storytelling to the demise of storytelling to life.

If you crack the hardcover (available from Simon and Schuster December 5) expecting something that begins with, “I arrived in Hollywood at age 35” and then meticulously runs through each of Mamet’s films, that’s not how it works. Oink Oink doesn’t read like a memoir. It doesn’t read like anything. Instead, Mamet’s had a few beers and keeps telling tales because he can see how much you enjoy them.

And he holds nothing back. Mamet’s not burning bridges, mind you. This isn’t a tell-all. To his credit, very few names are named. Mamet’s a guy’s guy, and he’s a gentleman who’s successful and wise enough not to be bitter. Overall, he comes off as grateful for his career, even during the most grinding times. There’s a real affection for What Was, a wistful appreciation enhanced by the terrible reality of today’s Hollywood, what he accurately describes as “an unbridled reign of Virtue” that has destroyed The Art.

Mamet is 75 years old, wealthy, married to a beautiful actress (Rebecca Pidgeon — who is fluent in Mamet-speak. See: Heist — no, really, see it), and as accomplished as a writer can be. He’s won a Pulitzer, directed 11 feature films, earned two Oscar nominations (wuz robbed for The Verdict), and hasn’t earned a screen credit since 2008 — which I’m certain has nothing to do with the fact that he came out of the political closet that same year with an essay titled “Why I Am No Longer a Brain-Dead Liberal.”

“Yes, the business changed (died) and as I aged out of it and got sidelined because of my politics (respect for the Constitution, etc.), my work began to resemble that of postwar Trobriand Islanders.” He then explains what he means by “Trobriand Soldiers,” which manages to illuminate his point while being funny and educational. That would sum up how the whole book reads if there was tossed in the story of Ramon Novarro’s death-by-silver dildo.

And that’s the primary reason Oink Oink works. It’s fun, and Mamet’s not out to settle scores or even polish his own apple. He admits to many mistakes (a meeting he blew with Denzel Washington, turning down the opportunity to write Raging Bull and Once Upon a Time in America — yikes). Those names he names are generally people he admires (Danny DeVito, Alec Baldwin, Val Kilmer, Sue Mengers, Joe Roth) or people he admires despite their sins against The Script (Scott Rudin, Robert De Niro, Mike Nichols).

I was prepared to read the book in the voice of Joe Mantegna, Mamet’s longtime friend and collaborator, but the book isn’t written in the style we’ve come to expect from the author. It’s something all its own — playful, energetic, frequently hilarious. The prose took some getting used to. Granted, I’m too literal for my own good, someone who understands Shakespeare about as well as Vulcan, but once my simple mind adjusted, I couldn’t put it down. The book arrived Wednesday afternoon. I finished it off early Friday morning.

It’s the infectious spirit that hooks. Oink Oink might only be 225 pages, but Mamet refuses to waste words, which creates an avalanche of anecdotes, insights into the craft of storytelling, and an intelligent and biting (but never angry) criticism of what’s gone so wrong with The Industry today — diversity over merit, filmmakers putting the preen of their own virtue above a good story populated with interesting characters, movies as carnival rides, and too many goddamned producers.

“Our current drivel,” he calls it…accurately.

And Mamet is no hypocrite.

One of his targets is the trope. For example, he has no patience with those dramas where the troubled protagonist seeks therapy and is then cured with a therapeutic “breakthrough,” a repressed memory told to the audience in flashback. Too pat. Too clean. Too forgettable.

Mamet suggests the audience not be told. Instead, he would have our protagonist whisper the breakthrough in the therapist’s ear. That, he says, is drama. First, the audience can relate to what is unspoken because we fill in the blank with our own experience. Second, as we try to crack the mystery, it makes for a memorable movie night. Then, after he’s digressed for a few paragraphs (prepare for lots of digressions), Mamet returns to the subject:

The reader may still be disturbed or unconvinced by my suggestion of the protagonist’s whispering. What would he [the reader] remember had I actually written the obligatory confession? What does he remember of any of those speeches that he’s heard in films? But you remember the whispering.

Oink Oink is full of whispering. What are we to make of a middle-aged Paul Newman, who, upon meeting Mamet for the first time, said, “Hello. I just got laid.” We can only imagine Mamet and Val Kilmer getting drunk on the floor of a Star Wagon discussing the Commerce Clause. And what of a Robert De Niro, who didn’t speak to Mamet for ten years (after Mamet basically told him off for questioning a script) but still starred in four of Mamet’s films?

Mamet swoops about mixing his experiences with ribald tales (that might be true) from the Golden Era (see: dildo, silver), a few dirty jokes, and the occasional political thought. He’s such a skilled raconteur it works. There might be no logic to the sequence of the individual brush strokes; nevertheless, a whole picture does emerge. Maybe it’s more of a feeling than a picture. Regardless, it is Whole — a picture of what was: a brutal, unfair, unjust, maddening, ego-driven, greedy, moronic Industry that somehow still operated as meritocracy (butts in seats), and what we have now: an Industry so broken a stunt driver recently died because her gender and skin color trumped her experience. That’s a perfect (and tragic) metaphor for a DEI Hollywood whose pandering damages the art along with those being pandered to.

Mamet isn’t right about everything. He rewrites a few films. This is how I’d do it… His Man on Fire (2004) suggestion is so good it feels like it’s been sitting there this whole time. Hands off High & Low (1963). He’s correct that Jerry Lewis, Woody Woodpecker, and Red Skelton were never funny, but wrong not to tell us more about his great friend and collaborator Ricky Jay — one of the most unique talents of his time.

Mamet comes across as honest, a good guy, a loyal friend, and prickly writer. That’s to his credit — I mean, that he didn’t leave out the prickly.

You need not be familiar with Mamet’s work to enjoy Oink Oink, but if art means anything to you, I’d recommend you start here:

Screenwriter: The Verdict (1982), The Untouchables (1987), Glengarry Glen Ross (1992), Wag the Dog and The Edge (1997), Ronin (1998).

Director/writer: House of Games (1987), The Spanish Prisoner (1997), Heist (2001).

When you’re done familiarizing yourself with the above, remember “drivel” like Good Will Hunting (1997) has won screenplay Oscars and Mamet has not.

I will now return to pimping my own book, which is not a memoir but, like Global Warming, a piece of fiction…

Get a FREE FREE FREE autographed bookplate if you purchase John Nolte’s debut novel, Borrowed Time (Bombardier Books) in December. After your purchase, email JJMNOLTE at HOTMAIL dot COM with your address and any personalization requests.

Borrowed Time is winning five-star raves from everyday readers and is the perfect Christmas gift. You can read an excerpt here and an in-depth review here. Also available on Kindle and Audiobook.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.