CARACAS — Venezuela used to be known for many great things, among them its unfiltered, satirical, irreverent, politically incorrect, and no-holds-barred humor.

There was a time when we could freely express ourselves through it, laughing at everything and anything, especially ourselves.

In my youth, it was very common to turn on the television and see comedians express the problems of that Venezuela through comedy sketches. While I’m no comedian myself, I have made a fair share of internet memes, and that absurdist type of Venezuelan humor I was exposed to during my youth helped shape the way I tackle comedy as an adult.

Through humor we have been able to cope with the shortcomings of our small country since long before Hugo Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution rose to power. As such, Venezuelan comedy has always been intrinsically linked to the nation’s politics. Unfortunately, the once-celebrated socialist revolution has robbed us of comedy through censorship laws and now, while humor still remains an inalienable coping mechanism for the tragedies we’ve lived through, it has been neutered, and we as a country can no longer freely produce comedy of the caliber that we used to.

Just like telenovelas and other audiovisual works of drama, there was an abundance of comedy shows on our national television channels and radio stations, some more “risque” than others. Snippets of the Venezuelan comedy of times past can still be found preserved in social media and YouTube, but a sheer majority of it has now been lost.

Certainly, the most emblematic Venezuelan comedic show of all times was Radio Rochela (which loosely translates to Radio Bustle).

The simplest way that I can describe what Radio Rochela was is that it was kind of a Saturday Night Live type show — back when it was funny, or so I’ve been told — but the Rochela was even more unfiltered, and no politician at the time was exempt from satire and ridicule.

Many in the country would punctually tune in to the now-extinct Radio Caracas Television (RCTV) channel every Monday night. From the rather stereotypical Portuguese migrants that run grocery stores in the country, to a mockery of Hispanic machismo, the Rochela provided entertainment and laughter for five decades — until Hugo Chavez forcefully shut down RCTV in 2007.

The show, alongside RCTV, tried to survive by being broadcasted outside of Venezuela and through the internet, but its efforts came to an end in 2010.

Venevision, the other major national television channel in the country, had two emblematic sketch comedy shows: Bienvenidos (“Welcome”) and Cheverísimo (“Very Cool”).

Bienvenidos was also a sketch show that satirized aspects of Venezuelan culture, but it tended to be the more risque show of the bunch, frequently featuring scantily-clad women, double entendre, and a “flasher” character.

On the other hand, Cheverísimo was more akin to Radio Rochela in terms of content and tone. One of the most emblematic sketches in Cheverísimo’s repertoire was comedian Jorge Tuero’s Rico Mac Rico (Rich Mac Rich). Rico Mac Rico involved a poor man who lived the fantasy of being rich and opulent, serving as a reflection and critique of the Venezuela of the 1990s and the lives of the poor versus the more opulent. All of his sketches ended with the phrase, “goverments pass, but hunger stays.”

Another of Tuero’s emblematic characters, El Terror del Llano (“The Terror of the Plains”), was a satire of the macho culture of Venezuelans in the plains region of the country.

Many more sketches and notable characters brought countless hours of entertainments to Venezuelans every week. All seemed to be well in terms of comedy until Hugo Chávez rose up to power in 1999. Venezuela’s irreverent comedy inevitably clashed with the Bolivarian Revolution’s plans and, slowly but surely, comedy began to be assaulted and censored.

In 2000, the Bolivarian Revolution had just rewritten our constitution and the country was getting ready for a “mega” general election. During those times, Venezuelan comedians had grouped together to satirize the entire process via a theater play known as La Reconstituyente (“The Reconstituent”), a play on words on the whole constituent process that had just “rebooted” the country through a new constitution.

As it is a theater play released at a time when smartphones did not exist, it is difficult — if not outright impossible — to obtain a complete recording copy of it, although low-quality recordings of a preview broadcast on television still exist on YouTube.

In the play, actors took the role of Hugo Chávez, former president Rafael Caldera, Cuban dictator Fidel Castro, and other Venezuelan politicians, satirizing each and every one of them to the point of ridicule. The Reconstituent was meant to be a theatrical trilogy, but criticism from the Bolivarian Revolution prevented the second and third planned parts from ever materializing.

By 2004, the Revolution had introduced a fierce media gag law known as the Law on Social Responsibility in Radio, Television, and Electronic Media (RESORTE). While the law presented itself as intended to “respect freedom of expression and information without censorship,” it is still used by the socialist regime to censor media in Venezuela to this day.

RESORTE was also used to censor and neuter comedy critical of the revolution, as the law prohibits content that could “incite or promote hatred,” “foment citizens’ anxiety or alter public order,” “disrespect authorities,” “encourage assassinations,” or “constitute war propaganda.”

Ever since the law was passed – and most notably after Hugo Chávez’s forced closure of RCTV in May 2007 – the nation’s remaining television channels and radio stations began to self-censor to survive. That has not stopped the socialist regime for continuing to shut down media, with 100 radio stations being shut down by the Maduro regime in 2022 alone.

In 2005, Venezuelan comedian Laureano Márquez published an open letter addressed to one of Hugo Chávez’s daughters, Rosines, through the Venezuelan newspaper Tal Cual. The letter, while being of an informal but respectful tone, playfully requested Chávez’s daughter intevene to stop, among certain things, her father from falsely branding everyone who opposed him a “fascist.”

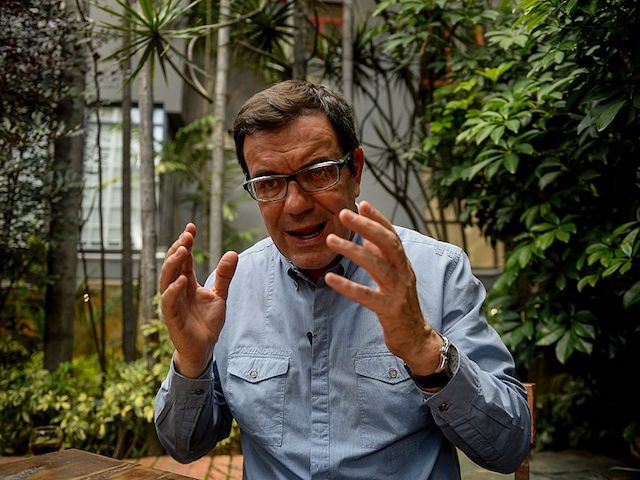

Venezuelan humorist Laureano Marquez speaks during an interview with AFP in Caracas, on December 14, 2016. (FEDERICO PARRA/AFP via Getty Images)

The letter drew the immediate ire of Chávez and the Bolivarian Revolution imposed a 38-million-bolivar fine on the newspaper ($17.6 million at the time, currently $3.3 billion).

Some Venezuelan comedians had attempted to continue practicing political comedy through new means, such as lending their voices to the short-lived web cartoon series Isla Presidencial (“Presidential Island”) made outside of Venezuela that “softened” the repercussions of criticizing Chávez (and then Maduro) by also satirizing the region’s presidents, whether they were from the left or right.

By the time Maduro assumed the reins of the socialist revolution in 2013, all of the emblematic Venezuelan comedy shows that many grew up with were long gone. With no way to exercise comedy through television or radio, Venezuelan comedians found in theaters their new main outlet of expression, especially when it came to political comedy. But by 2016, the Maduro regime, which controls all public theaters in the country, began to ban comedians it disapproved of from using the theaters in any capacity, leaving only a handful of private theaters at their disposal.

The coup the grace on Venezuelan comedy and satire was the “anti-hate speech” law passed by the Maduro regime in 2017 – an ambiguous piece of legislation that can get anyone living in this country up to 20 years in prison for publishing or expressing content that the regime deems “hate speech,” be it text, radio, television, or social media content.

The Maduro regime has used the law to arrest citizens in the past that have dared satirize the regime in the same vein that comedy shows used to freely do so in the past, with 72-year-old Venezuelan woman Olga Mata being the most recent notable case.

In April, Mata published a viral video on the Chinese platform TikTok that employed food-related puns and dark humor to satirize members of the Maduro regime. The elderly woman appeared in the video making arepas, a traditional Venezuelan corn cake pretending to sell varieties named after various Maduro regime henchmen. One of the arepas, for example, was named the “Diosdado Cabello,” after the drug kingpin head of Maduro’s political party, and Mata joked it came stuffed with cocaine. She also joked the arepa named after First “Combatant” Cilia Flores, Maduro’s wife, was nicknamed “the widow,” apparently wishing death on the dictator.

The regime quickly retaliated and arrested the elderly woman and her son under “incitement to hatred” charges. Mata was forced to record a public apology to the socialist regime in exchange for her freedom.

By now, many of the comedians that used to bring joy to Venezuelans through television sketches before the arrival of the Bolivarian Revolution have either passed away or have left the country. A couple of them were recently awarded by the U.S. Congress for their contributions to the Hispanic community in the United States.

It’s no secret that we’re now one of the unhappiest countries in the world, and with good reason. Laughing at the state of things and at socialism as a whole did not solve the problems in our country, and certainly did not stop the socialist regime from doing everything that they have done in the country so far.

Socialism is certainly no joke but, as Venezuelan comedian Laureano Márquez said to the BBC in 2014, “the only tool we have left is humor,” and I include myself among those that still tackle the absurdity that is Venezuela through humor and satire — although I, for my own sake and that of my brother’s (who is under my care), I have to restrain myself more often that I’d like to admit as long as I’m within Venezuelan borders.

Christian K. Caruzo is a Venezuelan writer and documents life under socialism. You can follow him on Twitter here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.