Mr. President, 1975 is on line one, and 1979 is on line two.

It seems like Joe Biden, first elected to public office in 1970, is destined to relive all the national policy debacles of the 1970s. Today, near the end of his long career, the 46th president is becoming strangely reacquainted with the mistakes and frustrations of the 37th, 38th, and 39th presidents: Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and–most pointedly of all–Jimmy Carter.

Surely Biden remembers those presidencies well. He served in the U.S. Senate during all three of them. And yet even so, he seems unable to avoid falling into some of the same traps. Perhaps Biden has gotten a little fuzzy on some of the key details, the memory of which would have saved him grief. In fact, in recent months, this author has recalled the similarities between Biden policies of the 2020s and the policies of the 1970s concerning energy and the environment, crime, the economy and inflation, and a rival superpower. Short version of all this history: The 1970s were not good years for America. And now half a century later, the policies of the 2020s seem eerily similar.

So let’s look at the current debacle in Afghanistan through this historical lens.

We can start with Biden’s press conference at the White House on July 8. When asked about the prospect of a collapse of the Afghan government, Biden reached back to the moment in April 1975 when the U.S. military evacuated the U.S. embassy in Saigon, the capital of the former South Vietnam, via helicopter. As Biden said with confidence barely five weeks ago, “There’s going to be no circumstance where you see people being lifted off the roof of [an] embassy… of the United States from Afghanistan.”

Here, Biden is referring to events from nearly half a century ago–long before most Americans were even alive–and so it’s worth taking a moment to recall this history, to see how we got to that point where we fleeing from our own embassy in 1975 And if we do, then the parallels to 2021 will be even more clear.

Back in the 1960s and 70s, the U.S. government attempted to defend South Vietnam from communist North Vietnam, which was in turn being supplied by both the People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union (now Russia). Fighting communism, as part of the overall Cold War, was a reasonable idea, and yet Uncle Sam has never seemed to have the knack for getting the locals to share in the burden of the occasional hot war. Moreover, our attempts to “nation build” South Vietnam met with little success.

So in 1975, after spending trillions in today’s dollars—as well as, far worse, suffering the loss of more than 58,000 killed and hundreds of thousands more physically wounded and mentally scarred—the U.S., was forced to evacuate its Saigon embassy from the air, as North Vietnamese troops and tanks swarmed below.

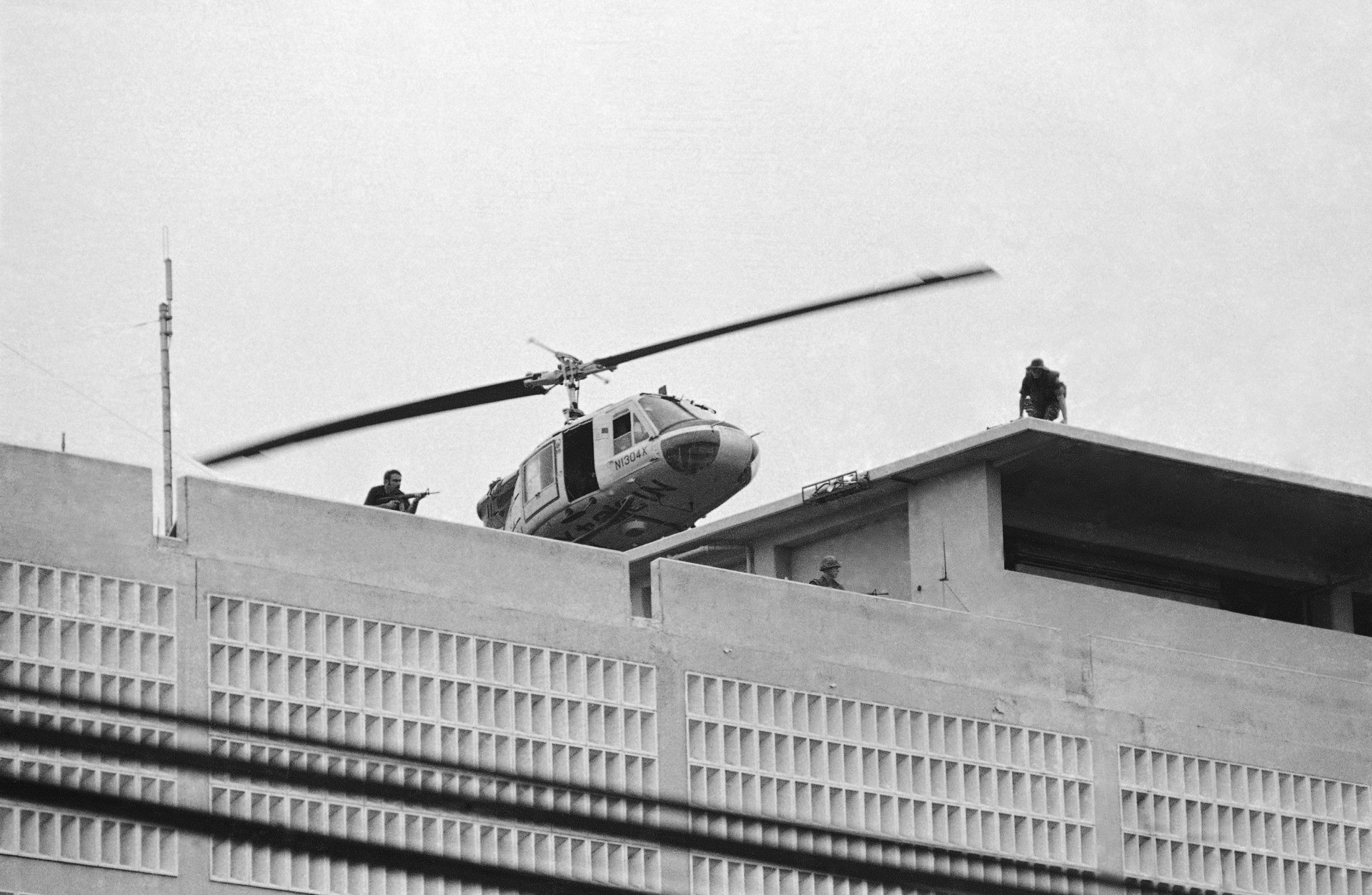

Observers have been quick to juxtapose the August 15 image of an American helicopter over the U.S. embassy in Kabul with similar images of a U.S. chopper hovering over our embassy in Saigon in 1975. As one Breitbart News headline had it: “Biden’s Saigon: Videos Reveal Utter Chaos at Kabul Airport as Taliban Conquers Afghanistan.”

A South Vietnamese air force Chinook helicopter lifts refugees from embattled Xuan Loc area east of Saigon, April 13, 1975, as government and Communist forces continue their fight for control of the provincial capital. (AP Photo)

A U.S. Marine helicopter takes off from helipad on top of the American Embassy in Saigon, Vietnam, April 30, 1975. (AP Photo/Phu)

A U.S. Chinook helicopter flies over the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, Afghanistan, Sunday, Aug. 15, 2021. Helicopters are landing at the U.S. Embassy in Kabul as diplomatic vehicles leave the compound amid the Taliban advanced on the Afghan capital. (AP Photo/Rahmat Gul)

A North Vietnamese tank rolls through the gate of the Presidential Palace in Saigon, April 30, 1975, signifying the fall of South Vietnam. (AP Photo)

A Taliban fighter sits on the back of a vehicle with a machine gun in front of the main gate leading to the Afghan presidential palace, in Kabul, Afghanistan, Monday, Aug. 16, 2021. The U.S. military has taken over Afghanistan’s airspace as it struggles to manage a chaotic evacuation after the Taliban rolled into the capital. (AP Photo/Rahmat Gul)

A U.S. civilian pilot in the aircraft doorway tries to maintain order as panicking South Vietnamese civilians scramble to get aboard during evacuation of Nha Trang Tuesday, April 1, 1975. Thousands of civilians and South Vietnamese soldiers fought for space on the aircraft to Saigon as communist forces advanced following the fall of Qui Nhon, to the north. (AP Photo)

Afghan people climb up on a plane and sit by the door as they wait at the Kabul airport in Kabul on August 16, 2021, after a stunningly swift end to Afghanistan’s 20-year war, as thousands of people mobbed the city’s airport trying to flee the group’s feared hardline brand of Islamist rule. (Wakil Kohsar/AFP via Getty Images)

Nowhere to go and nothing to do, South Vietnamese refugees from Hue and the northern provinces pause on the dock waiting for the government to relocate them to the central coastal area at Da Nang in Vietnam, March 28, 1975. (AP Photo/Dang Van Phuoc)

Afghans crowd at the tarmac of the Kabul airport on August 16, 2021, to flee the country as the Taliban were in control of Afghanistan after President Ashraf Ghani fled the country and conceded the insurgents had won the 20-year war. (AFP via Getty Images)

Afghan people climb atop a plane as they wait at the Kabul airport in Kabul on August 16, 2021, after a stunningly swift end to Afghanistan’s 20-year war, as thousands of people mobbed the city’s airport trying to flee the group’s feared hardline brand of Islamist rule. (Wakil Kohsar/AFP via Getty Images)

Those Who Don’t Remember the Past Are Doomed to Repeat It

A new and tragic meme is born: Kabul is the new Saigon. So we should ask: Why does this keep happening to us? Isn’t the civil and military leadership of the country supposed to be made up of experts who, you know, figure these things out?

One of the reasons we failed in Afghanistan is that we failed to learn the lessons of Vietnam. And the most obvious of these lessons is that it’s impossibly hard for Americans to persuade a proud and stubborn country to become like the U.S. (And yes, there are other lessons too, such as the need to avoid fighting ground wars in Asia, especially when the enemy can be easily resupplied. The fault for not learning these lessons lies with Biden’s predecessors too.)

In the meantime, back home in the United States, the Vietnam war effort was undercut by an incompetent and untrustworthy American Establishment promising “light at the end of the tunnel” when there was no true light and so suffering from a chasmic “credibility gap.” Thus in 1975, South Vietnam came crashing down. It was without a doubt a tragedy for the South Vietnamese people, and yet there was no way that the U.S. could or should have stayed to fight in Vietnam forever.

So now to today. It’s reasonable to think that we should never have made such an enormous and open-ended commitment to nation-build Afghanistan. After 9/11, we could have clobbered the Taliban and crushed Al Qaeda and then left. Call it a punitive expedition, not a nation-building exercise.

Yet the American Establishment, including presidents of both parties, said that we should stay and modernize Afghanistan. It was a plan that might have seemed nice on a PowerPoint in Washington, DC, but not so great on the ground in Kandahar. Indeed, as during Vietnam, the American Establishment proved itself incompetent and untrustworthy.

For instance, less than a month ago, General Mark Milley, the chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, declared at a press conference, “The Afghan Security Forces have the capacity to sufficiently fight and defend their country.” In the harsh assessment of pundit Nick Short, “Milley had no idea what he was talking about.”

C-SPANOn August 15, conservative pundit Saagar Enjeti summed up the whole two-decade disaster: “There was no ‘Afghan Government.’ It was a fiction the entire time backed only by US dollars, US blood, and US military might. The lie of building up a credible ally for 20 years falls in just 3 weeks.”

From Saigon 1975 to Tehran 1979

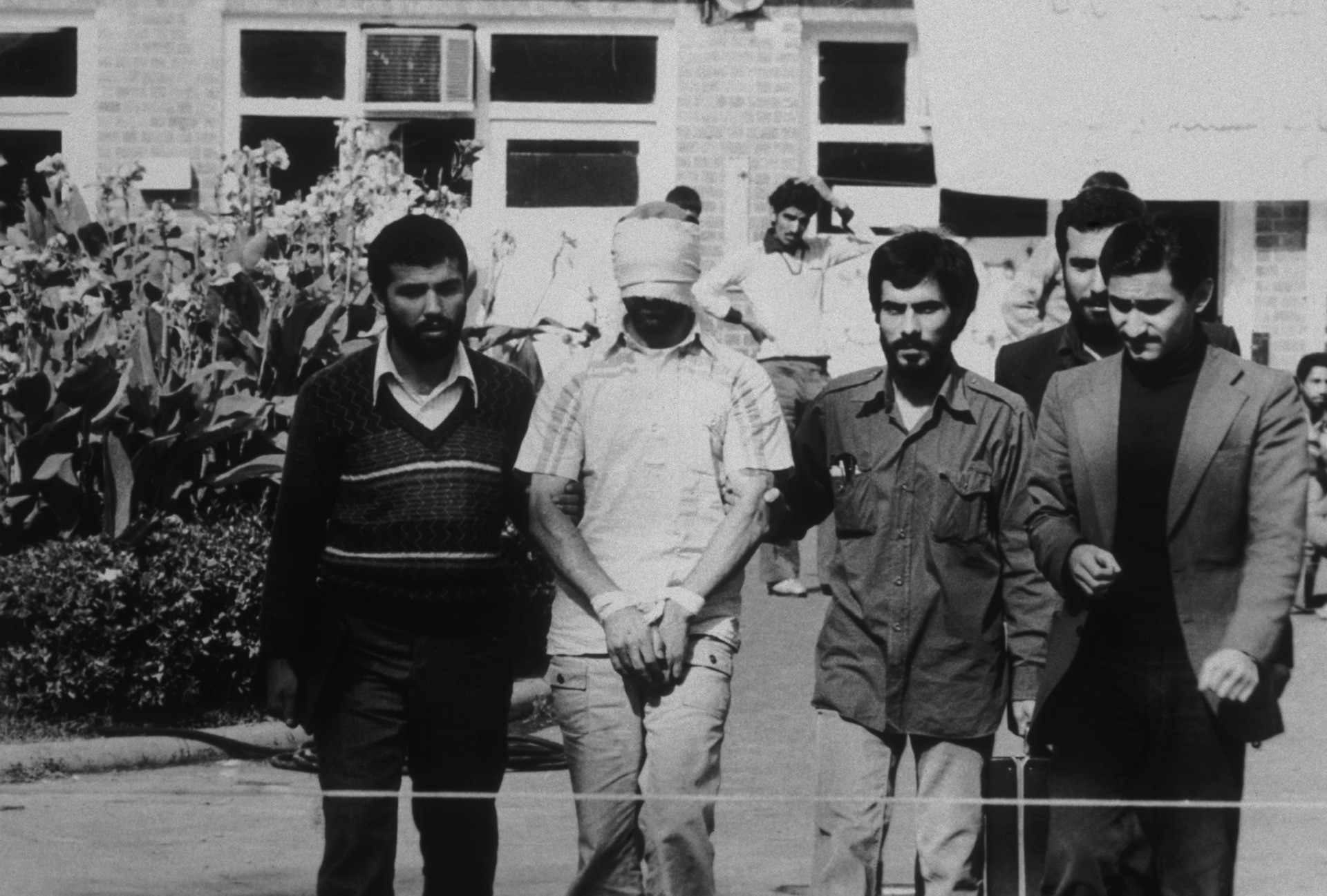

And while the Kabul = Saigon parallel is bad enough, there’s another 1970s parallel waiting to burst forth. And that is Tehran 1979. Those of us who were alive and old enough to pay attention to the news in 1979 remember well the hostage crisis that began that year, when Iranian militants stormed the U.S. embassy, holding our diplomats and others hostage for 444 long days.

The whole ordeal was a humiliation for the U.S., and no helicopter could save us, although in April 1980, a U.S. military helicopter rescue mission tried and failed, leaving eight American soldiers dead. The military might have had its bad luck on that missions, and yet the basic problem was that our troops were given an impossible mission.

An American hostage being paraded before the cameras by his Iranian captors. Following the Iranian revolution over fifty American hostages were taken and only released after four hundred and forty-four days. (Photo by MPI/Getty Images)

A charred body lies within the scorched wreckage of an American C-130 Cargo aircraft in the Iranian desert of Dasht-E-Kavir, approximately 500 kilometers from Tehran, on April 27, 1980. The mission to free 50 American hostages from the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran was aborted due to equipment failure. The plane collided with a U.S. helicopter and eight servicemen were killed. (AP Photo)

So how is Kabul today potentially akin to Tehran in 1979? Here’s how: As of this writing, Americans are being evacuated from Kabul and most likely elsewhere around the country, and yet we have no idea exactly how many Americans are in the country. After all, over the last two decades, not only has the uniformed U.S. military been all over Afghanistan, but so have innumerable American diplomats, intelligence workers, drug enforcement agents, aid workers, contractors, journalists, businesspeople, missionaries, as well as, of course, wanderers, adventurers, and who knows who else. And of course we’re now sending troops back to Afghanistan, and so are other countries.

So with all this human presence, here’s a grim but safe prediction: Plenty of Americans as well as others from the West are going to find themselves as prisoners of the Taliban.

After all, the collapse of Afghanistan has happened so quickly. To illustrate the speed at which Washington officialdom has been overwhelmed by events, we might remember the overconfident words of Secretary of State Antony Blinken, testifying before Congress on June 7: “Whatever happens in Afghanistan, if there is a significant deterioration in security. . . I don’t think it’s going to be something that happens from a Friday to a Monday.” Yet in point of fact, that’s exactly what happened from Friday, August 13 to Sunday, August 15. The Afghan military melted away; Afghan government officials surrendered, switched sides, or fled; and the whole capital of Kabul—population 4.35 million—fell like a ripe apple. (Speaking of credibility gaps, that same day, Blinken said that the U.S. mission in Afghanistan had been “successful.”)

So now it appears that some and perhaps many Americans have fallen into the Taliban’s trap. As Breitbart News reported late on August 15, sources including Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) and New York Times reporter Maggie Haberman were speaking of U.S. citizens left behind. Upon reflection, this should be no great surprise. After all, if one were an American in Kabul, one might have put faith in the words of, for instance, Blinken and Milley and felt safe in that fortified city. And in any case, it’s not possible to move lots of people around—especially on short notice, and when the Taliban is besieging the airport and other landing zones, even as panicked people were thronging airport runways, thereby hindering planes as they attempted to take off and land.

So all this, plus Murphy’s Law, suggests that the Taliban will reap a huge hostage-haul. On the afternoon of August 15, the New York Times reported that more than 100 journalists employed by U.S. government radio stations have been trapped in the country. “Journalists are being left behind,” said Rateb Noori, the Kabul bureau news manager of Radio Azadi, a branch of the U.S. government’s Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty. As of now, there’s no way to know how many, if any, of those journalists are American citizens or have relatives in the U.S. or have some other sort of American residency status. And yet it wouldn’t be surprising if some do and all of them, of course, have a link to the U.S. Which is to say, their capture could be a propaganda prize for the Taliban, and perhaps a hostage-bargaining chip. And the fate of those particular journalists aside, it’s likely that many American and Western reporters, technicians, as well as others, are going to end up in the clutches of the Taliban.

It’s bad enough that Kabul in 2021 is an acid-trip of bad nostalgia to Saigon in 1975. It would be even worse if Kabul turns into a replay of Tehran in 1979, complete with hostages on videos, ransom demands, agonizing negotiations, and perhaps valiant but doomed rescue attempts.

In other words, Joe Biden today is staring at an uncomfortable mirror from decades past: When he gets back from his vacation, the 46th president might look at his reflection and see instead the 39th president, Jimmy Carter. Specifically, Biden should remember Carter’s and the nation’s ordeal during the 1979-1981 hostage crisis.

And we know know our history, we know what happened to Carter in his next presidential election.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.